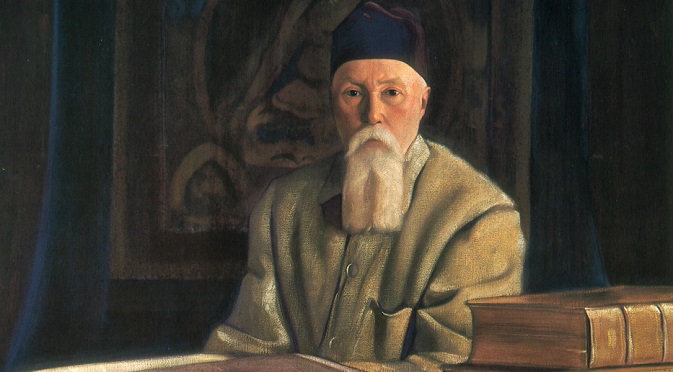

A painting of Nicholas Roerich by his son Svetoslav

Few people have ever brought Russia and India closer than the painter, writer and philosopher who lived out his final years in the Kullu Valley.

Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947) was an artist, poet, traveller and one of the most enigmatic figures of the 20th century. He was called all sorts of things from a prophet of a new religion, to a Soviet spy and a leader of Freemasonry. Some even believed that he was a reincarnation of the Buddha. Few people have ever brought Russia and India closer than the painter, writer and philosopher who lived out the final years of his life in the Kullu Valley.

A long journey

Roerich found fame early on. He painted, wrote short stories and was fascinated by archaeology. After high school, he entered the Academy of Arts in the painter Kuindzhi’s workshop. Roerich revered Kuindzhi, calling him a “guru” and “master.” When he was 30 years old, Roerich became a member of the Imperial Academy, and he happily signed his name “Roerich the academician.”

Roerich married a woman who was enthralled by the esoteric—everything supernatural and otherworldly. She had prophetic dreams. Before Roerich proposed to her, she dreamed that her deceased father entered her room and said, “Lilya, marry Roerich.” So they married.

Under his wife’s influence, Roerich too became interested in the occult. The couple hosted spiritual séances. This was at the turn of the century, a turbulent mystical period, when everyone—even the members of the Tsar’s family—was infatuated with magic and the Orient.

Helen Roerich then had another prophetic dream: she saw a man with a glowing face. She interpreted the dream as a mystical encounter with the Master. Roerich was also interested in the Orient. He asserted that in past lives, he was Leonardo da Vinci and the Dalai Lama. He and his wife devoured books about Indian philosophy and dreamt of travelling to Asia. They believed that the mountains held Shambhala, the place where the inner and outer worlds converge.

The 1917 Revolution was viewed with horror by Roerich. He wrote that it was an “uprising against knowledge, an alignment with squalor.” He was surprised as to why “rational beings can behave like lost madmen in human form.” The Roerichs fled from this chaos to the Himalayas. There, in a small temple on the slope of a mountain, they sought the Masters and Mahatmas, the great teachers. It was a pivotal event in their lives. The Mahatmas explained to Roerich that the Russian revolution was not only a disaster, but also a portent. So they sent him to Moscow with a mission. In Moscow he found Georgy Chicherin, the minister of foreign affairs, and delivered a parcel from the Tibetan lamas. In addition to a letter, the lamas sent the minister a box with sacred Buddhist earth. The letter said, “We are sending earth to the grave of our brother, Mahatma Lenin. Please accept our greetings.” Lenin was already dead. The lamas not only honoured his memory, but also recognized him as a Mahatma. It is a remarkable story—but all the stories involving Roerich are remarkable.

.jpg)

The lamas also wrote to Chicherin that Communism closely resembled Buddhism, and that this was a step to a higher consciousness, a higher stage of evolution. In addition, they said they were ready to engage in talks with the Soviet Union on the liberation of India, which was ruled by England. This delighted the Bolsheviks, and they promised Roerich that they would help him. Chicherin called him a “half Communist–half Buddhist.” There is even a theory that the Cheka recruited Roerich in Moscow. But why the Cheka for such a man, who was utterly not of this world? Such people are not suspected of being spies.

From Moscow the Roerichs set out on an expedition to Tibet. The journey was arduous. The men rode horses; Helen Roerich was carried on a stretcher. There were swampy flatlands all around. Below lay deep gorges in which the wind howled. When the travellers reached ataltitude of 4,500 metres, it became hard to breathe. Roerich’s son, Yuri, nearly died. He fell off his horse and lay on the stones, pale with a weak pulse. The others brought him back to consciousness with difficulty. The money and medicine ran out. Some members of the expedition died, but Roerich did not succumb—he wanted to reach Shambhala.

In Buddhist mythology, Shambhala is the symbolic centre of the world, surrounded by snowy mountains that resemble a lotus. According to legend, the “centres of wisdom” open up to those who make it there. The lamas hinted to Roerich that Shambhala is a spiritual understanding and is located in the inner world, not the outer one. However, he did not believe this. He was certain that this place truly existed and that he got very close to it. The English declared Roerich a Soviet spy and forbade the expedition to advance. He had to turn back.

There were a few more attempts to reach Shambhala; Roerich fought to the end. He secured the support of the Queen of England, the Pope and U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt. He found money for the expedition. However, nothing came of this. He lived in India until his death. At the end of his life he started to look like a Mahatma: he had a shaved head, gray beard and deep, wise eyes. These eyes spurred legends. One priest, looking into Roerich’s eyes, said, “What windows to the soul!” It was said that Roerich’s look made people’s hair turn gray. Many legends about him circulated. For example, the Tibetans believed that bullets would not hit him.

In his old age, he suddenly decided to return to Russia. He started packing his paintings, writing letters and saying goodbye to India. The farewell agitated him so much that before his departure Roerich lay down and did not get up. In accordance with Indian tradition, his body was cremated on a funeral pyre in front of his home. Then, a stone was placed there. The stone bears an inscription: “The body of Maharishi Nicholas Roerich, great friend of India, was committed to fire on this spot.”

Roerich belongs to all humanity. He built Orthodox chapels, received the blessing of the Pope and created Buddhist paintings. He wanted to create a peaceful religion, a cult of Light and Knowledge. It was a grand idea. Someday it will be realized.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.