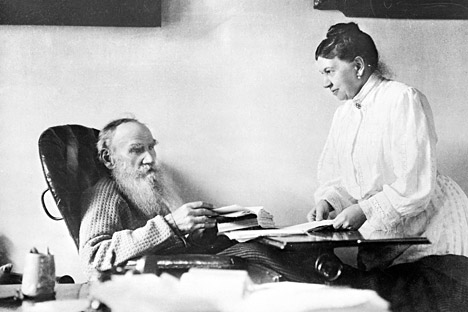

Sophia copied the entire text of “War and Peace” seven times. Source: Ignatovich / RIA Novosti

Sophia Tolstoy

The marriage of Sophia Bers to Leo Tolstoy lasted 48 years and her support helped him produce the epics “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina.” It was Sophia who encouraged him to give up the habits and addictions of his youth. Prominent writer, hero of the siege of Sevastopol, Tolstoy was also a drinker, gambler and womanizer. He confessed it all to Sophia, promising “not to have any women in our village, except for rare chances, which I would neither seek nor prevent” – a witty excuse!

The poverty of Tolstoy’s estate, Yasnaya Polyana, shocked the young Sophia. The bed was without blankets, the dinnerware was old and the rooms in disrepair. Sophia ultimately restored and maintained the rural estate, adding to the chores of wife and mother. But what gave her joy, she said, was the work she did to nurture Tolstoy’s writing.

Sophia became Tolstoy’s secretary, scribe and agent. She copied the entire text of “War and Peace” seven times, and promoted her husband’s works (she even contacted Dostoevsky’s widow for advice). "I've never felt my intellectual powers, and even all my moral powers, so free and so capable of work" – Leo Tolstoy wrote during the happiest times of their marriage.

The difficulties began much later when Tolstoy developed a new philosophy near the end of his life. Tolstoy still wrote his wife long love letters, but already began denying the concepts of family and property. “I can’t tell where we went apart, but I had no strength to follow his teaching,” Sophia wrote. Finally, depressed and in disarray, Tolstoy wandered away from his estate.

Sophia reached Leo at a small railroad station where he lay dying, only to witness her husband’s last breath. The will to finish the complete edition of Tolstoy’s works helped Sophia overcome her grief. “I hope people will be lenient with the one who may have been too weak to be a wife of a genius and a truly great man,” she wrote.

Anna Dostoevsky

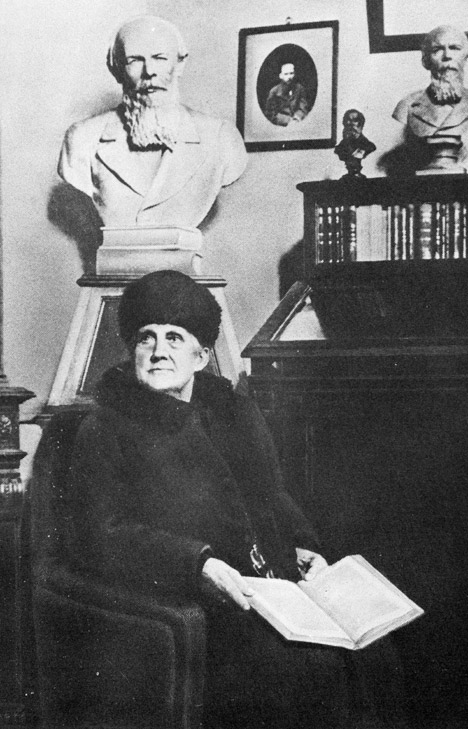

Anna Dostoevsky wrote two biographical books about her husband ('Anna Dostoyevsky's Diary in 1867,' 'Memoirs of Anna Dostoyevsky'). Source: V. Krechet / RIA Novosti

Dostoevsky proposed to his stenographer, 20-year old Anna Snitkina, only a month after their first meeting. It was a creative and hectic month, however. Anna helped him finish his latest commission “The Gambler” and retain the rights to all of his work, which had been claimed by a greedy publisher. “My heart was filled with pity for Dostoevsky, who survived the hell of exile. I dreamed of helping the man whose novels I adored so much,” Anna wrote in her memoirs. In her, the disillusioned 45-year old writer found a woman completely dedicated to him and his work.

Dostoevsky was a hopeless gambler. After the marriage, the family had to flee Russia because Dostoevsky’s creditors hunted him for payment. Yet he continued gambling in Europe, sometimes having to pawn his wife’s dresses and jewelry. Anna treated his passion as a disease, rather than a vice. Once she gave him the last money that the family had to support itself. According to Dostoevsky, the disarming sincerity of this act allowed him to understand that Anna was “stronger and deeper than he knew.” He lost the money, but gave his wife two promises – never to gamble again, and to make her happy. He kept both.

Dostoevsky’s greatest novels were written with Anna’s help as secretary and soul mate; she had great empathy and compassion for his characters, sometimes crying as she took dictation.

During the last years of the writer’s life, his family finally overcame their financial straits, in large part thanks to Anna, who managed the financial affairs. His death was not the end of her love, as she dedicated herself to publishing his works and maintaining the writer’s museum. She never remarried, saying ironically “Who else could I marry after Dostoevsky? Tolstoy, maybe?”

Vera Nabokov

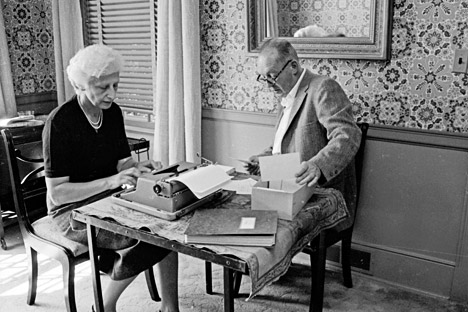

After Nabokov's death, Vera kept spending up to 6 hours a day behind the typewriter, translating his novels. Source: Getty Images / Fotobank

Vera Slonim married Vladimir Nabokov, a promising writer whose poetry she adored, in Berlin in 1925. Both of them – a Jewish lawyer’s daughter and the son of a well-known Russian politician – had fled Communist Russia, eventually settling in the United States.

Their union was rare and intense – it even annoyed Nabokov’s relatives since he trusted Vera to do everything. She wrote to publishers on his behalf and answered his calls; they even kept their common diary in a single book.

The Nabokovs always appeared in public together. During his tenure at Cornell University, Vera sat beside Vladimir at his lectures on Russian literature; they were so inseparable that rumors began to spread that Vera kept a gun in her purse to protect Nabokov. The gossip among friends was that Vera was really the writer, not the muse – in part because she sat behind the typewriter, while Nabokov wrote everywhere except at his table – in the bath, in bed, and in the backseat of the car. “The car is the only place in America where it’s quiet and no drafts,” Nabokov said. Vera, who also was his driver, used to take him deep into the woods and leave him alone, to write.

“Without my wife, I would never write a single book,” Nabokov would say. “Lolita” would have been destroyed if not for Vera, who repeatedly saved the manuscript from trashcans. Vera also shared his passion for chess and entomology.

In letters she wrote to friends, Vera complained about how hard it is to persuade Vladimir to take a break from work. But after his death, she did the same, spending up to 6 hours a day behind the typewriter, translating his novels, and editing at the age of 80.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox