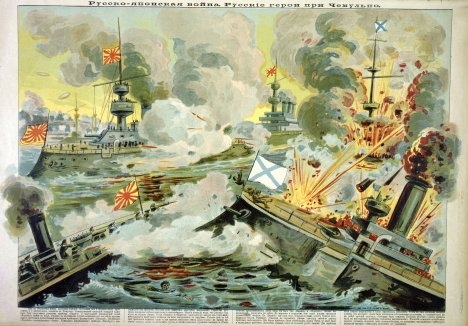

Russian heroes of the Chemulpo battle. Source: The British Library / Getty Images

The birth of a legend

Built for the Imperial Admiralty at a Philadelphia shipyard, the Varyag was launched on 31 October, 1899, to the accompaniment of a brass band and cries of “Hurrah!” from the 565-strong Russian crew. On learning that the ship was to be baptized with water, the American engineers shrugged and uncorked the bottle of champagne that had been prepared to be broken across the Varyag's bow as per the Western tradition. Neither they, nor the accepting Russian delegation, suspected that they were witnessing the birth of a Russian naval legend.

|

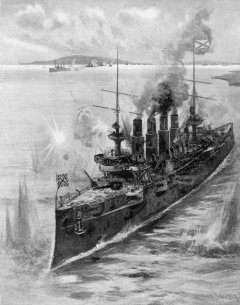

| Source: DPA / Vostock Photo |

Design defects became apparent almost immediately: a dynamo cylinder of the cruiser exploded. In fact, the cruiser's entire service life was blighted by various technical issues: - hardly had the mechanics fixed one problem than a new one emerged. Despite these difficulties, several years after its launch the Varyag set sail for the port of Chemulpo (now Incheon, in South Korea), where it was to attend talks on Korean neutrality. The empires of Russia and Japan had been at odds over the status of Manchuria and Korea since 1903: Japan sought the recognition of Korea as part of its sphere of influence, but Russia was unwilling to accede to these demands.

When the barely serviceable cruiser arrived at Chemulpo, it found the port filled with British, Italian, German, Japanese, French, and U.S. ships. On the morning of January 27, 1904, Imperial Japanese Navy Admiral Uryu Sotokichi sent an ultimatum to the captain of the Varyag, Vsevolod Rudnev, reading as follows: “As hostilities exist between the Empire of Japan and the Empire of Russia at present I shall attack the men-of-war of the Government of Russia, stationed at present in the port of Chemulpo, with the force under my command, in case of the refusal of the Russian senior naval officer present at Chemulpo to my demand to leave the port of Chemulpo before the noon of the 9th of February, 1904, and I respectfully request you to keep away from the scene of action in the port so that no danger from the action would come to the ship under your command.”

Historians believe that Capt. Rudnev should have used this chance to cross neutral waters and reach Russian shores. Even with its malfunctioning engines, the Varyag still beat Japanese warships in speed by three to five knots. However, following on February 8, 1904, a large Japanese naval force approached, trapping the ships inside Chemulpo harbour.

This left Rudnev in a dilemma. Accepting battle would mean certain annihilation because the cruiser had no side protection, and its firepower was significantly inferior to that of the Japanese ships. Capt. Bailey of the British protected cruiser HMS Talbot suggested that the Varyag be intered under the Union Jack as being unfit for combat. Rudnev, however, decided instead to engage the enemy in a bid to break out of the port. At 11:00 on 9 February the Varyag sailed out of Chemulpo harbour and opened fire on the Japanese forces.

Vsevolod Rudnev, Captain 1st Rank, later promoted to Rear Admiral, co-designed the theory of the ship’s floodability. He completed several circumnavigations. In 1905, Rudnev was sent into retirement for refusing to arrest members of his crew who had taken part in anti-government demonstrations. His military awards included over 20 orders, including the Order of the Rising Sun from the Japanese emperor.

The Varyag’s artillery crews were known as the best in the Russian Navy's 2nd Pacific Squadron – and for good reason. Although they sank at least three Japanese cruisers and one destroyer during the battle, the enemy’s advantage was too great. More than half of the Varyag's guns were put out of order and water started flooding in through the holes in the hull. The upper deck took a serious battering and was soon piled with the bodies of crew members, while the metal dinghies were pierced with shrapnel and the wooden ones burned. The engine room was knocked out and the rudder actuators were severed, forcing the ship to return to harbour. After a brief conference with his officers, Rusnev took the decision to scuttle the ship rather than surrender, and ordered the flood valves to be opened. The Varyag listed to port and sank.

Some historians hold that Rudnev misjudged the situation and sank a combat-ready warship, thus gifting it to Japan. The Varyag was eventually raised from the sea bed, made it to Japan under her own steam, and went on to serve for 11 years with the Japanese navy under the name Soya.

Crew losses

A total of 108 of the Varyag’s crew, or one in five, lost their lives. The wounded were collected by foreign vessels. Those captured by the Japanese, who were greatly impressed by the stoicism of the Russian sailors, were later released under the promise not to take further part in belligerent action.

None of the Varyag crew believed themselves heroes though, quite the contrary. The senior navigator, for example, was convinced that he and Rudnev would be court-martialed for losing the ship. Nonetheless, there was a war on, and the country needed a symbol of its servicemen's heroism and invincibility to boost the troops' morale. The Varyag was chosen as a fitting example, so a song was written that turned the ship into a legend.

Source: Youtube

Under the enemy flag

More than a decade later, after Russia and Japan had re-established diplomatic ties, Moscow bought the Varyag from Tokyo and returned her to the Russian navy. It turned out, however, that the cruiser was too crippled to be of any use to Russia as a warship.

Sailors and officers of the Varyag cruiser in Moscow, Russian Empire. Source: ITAR-TASS

It was therefore decided to have the Varyag overhauled in Britain. Shortly afterwards, the 1917 revolution broke out in Russia. Half the Varyag’s crew were sent back home, leaving eight seamen, the boatswain and a petty officer behind. In addition, the Liverpool wharf refused to repair the Varyag on credit when it turned out that the Bolsheviks had no money to pay in advance. In the end, the British stripped the cruiser of all guns and ammunition, right down to the rifle cartridges.

British sentries were put on guard outside the radio room and the Russian naval flag was lowered and replaced by the Union Jack. However, even the UK did not need the Varyag as part of its fleet and the ship was soon sold on to Germany as scrap metal. Not far out of Liverpool on her way to Germany, the Varyag came aground, then was cut up and loaded on a barge.

The operation was performed in great haste, so the Varyag's lower hull remained on the bed of the Irish Sea for over 80 years afterwards. It was still there when a Russian filming crew for the Rossiya TV channel found it in the summer of 2003. Remarkably, the sturdy metal hull had survived all these years underwater virtually intact.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox