Indus Valley ruins in Kutch, India. Source: Ajay Kamalakaran

Few doubt the greatness of the Indus Valley or Harappan civilization, which is believed to have been at its full maturity between 2600 and 1900 BC. The script used by those who lived in the widespread civilization that stretched across northern India (and what is now Pakistan) has still not been deciphered.

Noted Russian scholars were fascinated with the impressive ruins and worked tirelessly to uncover their mysteries. Since there is prestige that comes with being the successor to a civilization that rivalled Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, many linguistic groups in India and Pakistan have tried to claim the Indus Valley as their own. Since Mohenjo Daro, is now in Pakistan’s Sind province, some misinformed people on both sides of the border proudly claim it as a Sindhi civilization. Then there is the discredited Aryan Invasion Theory, of which the debate will never end. Academicians from Moscow have strongly supported the hypothesis that the language and script used by the civilization were Dravidian in nature.

|

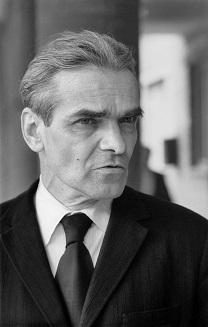

| Yuri Knorozov. Source: RIA Novosti / S. Solovjev |

The Dravidian hypothesis was supported by scholars like the Russian team headed by Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, noted Indian author and researcher Iravatham Mahadevan wrote in The Hindu in 2009. Knorozov, an epigrapher and ethnographer was best known for the important role his research played in the decipherment of the Mayan script. In the ‘Language of the Proto-Indian Inscriptions,’ the Russian scholar reached a conclusion that the symbols at the Indus Valley ruins represented a logosyllabic script. “There is reason to consider the Proto-Indian as being close to the Dravidian languages as far as grammatical structure is concerned,” he wrote.

Using a computer analysis, Knorozov suggested that an underlying Dravidian language was what people probably spoke in the Indus Valley. Knorozov felt that a sign in the Indus script of a man carrying a stick represented the posture of Yama, the god of death or Bhairava, a form of Shiva, and assumed that the man was a predecessor of the one the gods.

Knorozov worked closely with Nikita Gurov, one the greatest Indologists of all time in Russia and another strong proponent that the language of the Indus Valley civilization was probably an older Dravidian one. Few scholars in India could match the linguistic prowess of Gurov, who even managed to identify 80 words of Dravidian origin in the Rig Veda. Gurov and Knorozov co-authored Proto-Indica, a report on the investigation of Indian texts. The former argued in many publications that the Brahmi script was most likely connected to the Indus Valley script and not derived from one of the Semitic scripts. This is a major bone of contention between Western and Russian scholars.

Source: Ajay Kamalakaran

Knorozov continued to work on deciphering the Indus script right until 1995 when he was 73. He passed away four years later.

Other Russian scholars who researched the Indus Valley Script included Alexandr Kondratov, who was a prolific writer and author of books on palaeontology, cryptozoology and Atlantis and Irina Feodorova, who is best known for her research of Rapanui culture and Easter Island.

Later work by Kamil Zvelebil, a Czech academic supported the hypothesis proposed by Gurov and Knorozov. Zvelibil, an expert on Tamil, Dravidian and Sanskrit linguistics said, “The Dravidian affinity of the Proto-Indian language remains only a very attractive and quite plausible hypothesis.” Finnish scholar and Indologist Asko Parpola also believed that underlying language of the script was proto-Dravidian and said his readings were based on reasonable identifications of the signs’ pictorial shapes.

Iravatham Mahadevan described the efforts of Knorozov and Parpola as “pioneering.” He said, “What I found especially appealing in their work was that, unlike all previous attempts to decipher the Indus script, they were using computers to carry out sophisticated procedures on a scientific basis.”

While Russian scholars may have been at the forefront in the efforts to decipher the script, interest in this great civilization seems to be on the wane in Russia, according a leading Indologist who wished to remain anonymous. “After the deaths of Knorozov and Gurov, there was no one to carry on the mantle,” the Moscow-based academic said. “State funding has come down in humanities research and young people no longer have the passion for history that we did in the 1960s.” The Indologist cautioned that the work of his great peers would go in vain if the younger generation didn’t take an active interest. “Some argue that a lot of aspects of Russian culture came from India through Anatolia. More active and dedicated research is required to trace our long-established connections.”

For those interested in this topic, this writer would like to recommend, ‘The Soviet Decipherment of the Indus Valley Script: Translation and Critique,’ edited by Arlene Zide and Kamil Zvelebil.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox