In the 10th century, Russia adopted Christianity. But in some regions, the new religion had to be introduced with the use of coercion, since the Slavic peoples already had powerful pagan cults they were reluctant to give up.

The principal pagan gods were denounced, but the belief in local spirits refused to die out: For centuries, they warned people against natural dangers like drowning, carbon monoxide poisoning, or forest predators. Fairytale spirits also “taught” people to be polite, tidy, and hard-working.

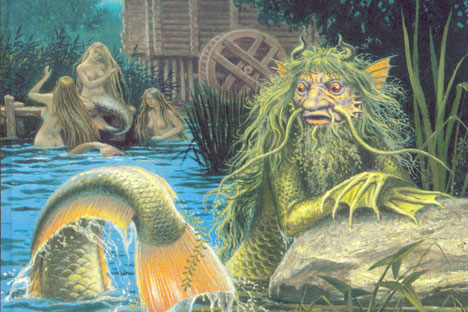

Vodyanoi

The Vodyanoi (literally “the one in the water”) is widely featured in folklore, because Russia is a country of rivers, lakes and seas, which were the main trade routes in times gone by. The cult of the vodyanoi was stronger in the northern part of Russia, close to the White Sea.

A vodyanoi is much more than a simple merman (mermen and mermaids were his servants and children) – he is the king of the underwater realm, and should be revered and feared as such. Black or blue-skinned, with a fin and a fishtail, he appears mostly at night, combing his tangled seaweed-colored hair on the river bank.

The rules of communication with a vodyanoi are simple. At night, any interactions with rivers and lakes were forbidden – be it fetching water, crossing or fishing. As for swimming, it was outlawed on big holidays, when many people were drunk; and it’s totally wrong to brag of your swimming skills and endurance at all times – the vodyanoi likes boasters most of all.

He doesn’t kill those who drown; he just takes them to his realm to serve him forever. That is why victims of drowning (as well as suicides) were not buried at Orthodox cemeteries – it might upset vodyanoi and cause drought or hail.

Leshiy

Leshiy never misses a chance to borrow some tobacco from a passer-by. Source: Open source

Leshiy(“the one in the woods”) is the most frightful, yet the most cheerful folklore spirit. Enormously tall and covered in animal-like fur, he is the master of all forest creatures. The leshiy is never placid, always traveling around the forest and playing pranks on careless visitors.

His favorite joke is to make you lose your direction in the woods – sometimes he does this by posing as a relative and offering to guide you home. But you can tell leshiy from your father or grandfather by some of his features: unnaturally long hair, animal eyes, and a brightly-colored article of clothing (a red hat or red waistband).

The leshiy always wants to smoke and never misses a chance to borrow some tobacco from a passer-by. He also loves celebrations and may even turn into a villager to sneak into a rustic party. But it’s crucial to drive away this lame guest as fast as possible – if he gets drunk and dances, the whole village will be turned upside down by the stomp of an ancient spirit gone wild.

To avoid being confused or chased by leshiy, one may read a prayer, but there are many other methods, swearing being one of the most effective. All Russian spirits fear obscenities, somehow even more than prayers. Also, to drive off leshiy, you can turn your clothes inside out, or change left and right shoes.

But it’s better not to mess with leshiy: Do not go into forest alone; do not quarrel, frolic or make noise in the forest. Above all, do not stay in the forest at night, and if you really have to, do not sleep on the forest path. All of this upsets leshiy, says the lore, but it is clear that these are precautions that prevent encounters with forest predators. Or it’s just them, collectively embodied by the lore in the image of leshiy? Maybe, but few have had the nerve to deny the existence of the forest king.

Domovoy

Source: Open source

Domovoi

There is no doubt that the domovoi (“the one at home”) is the foremost of all Russian spirits. Just like the British brownie, he lives inside homes and can help with household chores for a small edible reward, but that’s about all the similarities.

While brownies are small numerous creatures, a domovoi belongs to a certain family’s home and represents the spirit of the forefather – that is why he is often called “grandpa” and is said to be hundreds years old. When a family moves into a new house, the elder family member should invite the domovoi from their previous dwelling.

As a forefather, the domovoi cares about his kin and helps around the house – and sometimes, he can steal things for his own use. Living under the stove, in the most unholy and dirty place in the house, the domovoi is always present, but rarely shows himself.

His classic image is of a bearded old man with burning eyes without eyebrows, pricked-up horse ears and a tail. Most encounters with the domovoi occur at night, when he “smothers” sleeping people – not as a sign of aggression, but as a warning that something wrong is going on in the house or the family. If the family doesn’t heed his warning, the domovoi can be aggressive – making a racket, throwing things around the house, and injuring horses and cattle.

To avoid this, there are also some rules to follow. When leaving the house for a long time, one should “take a seat for the road” – after everything is packed, sit for a while in silence, bidding farewell to the household spirit.

At night, no cutlery or human food should be left on the table – the domovoi might use these for his own purposes or make the food “unclean”. No swearing is allowed in the house, especially at the dining table – the domovoi, like all other spirits, detests and fears swearing. Rows and quarrels also upset the domovoi, as well as general household untidiness.

While contemporary Russians, who live mostly in cities and towns, can rarely encounter vodyanoi or leshiy, belief in domovoi is still strong in some traditional families. The only thing the contemporary domovoi does not do is smother people, and you know why?

Because these days there are no stoves, and it seems that “smothering” by domovoi was a way Russian people explained carbon monoxide poisoning, which occurred very often in houses with no chimneys. As times move on, Russian folk spirits are slowly fading away, but they remain an important part of Russian culture.