Together in love, work and legacy

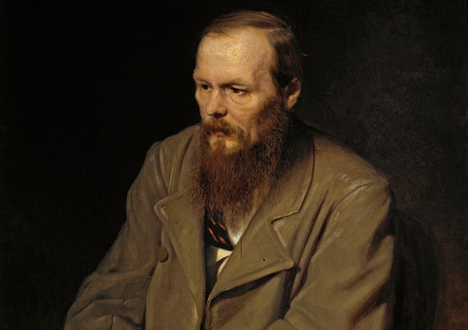

Nadezhda Mandelstam

Nadezhda Mandelstam worked to preserve her husband's poetic heritage, with the goal of publication one day. Source: Personal archive

Although she lived to 80 years old, Nadezhda Mandelstam spent less than 20 years with her husband, Osip Mandelstam. Their time together came to an abrupt end in 1938, when the great poet died in a camp near Vladivostok.

When she learned about her husband’s death, Nadezhda went on the run in fear of arrest. She spent the next 20 years moving from place to place, living a nomadic existence that took her from Moscow to Central Asia.

During this time she taught English, worked on her dissertation, and all the while kept her most sacred treasure enshrined in her memory: hundreds of her husband's verses. Fearing that his poems would be confiscated if discovered, she memorized them all by heart.

They met in 1919 in Kiev, in a bohemian cafe that Osip Mandelstam wandered into by chance. According to Nadezhda, they came together in a “carefree and natural way.” She writes, “Even then there were two properties within both of us that lasted throughout our lives — we were both easy-going and conscious of impending doom."

Their attraction to each other grew into a strong love, so it was just as “natural” for Nadezhda to accompany her husband on his wanderings around the country and deal with their perpetual lack of money. She never left him, despite his temporary departures to live with other women – including a female poet with whom he had a fleeting affair.

They had an almost symbiotic relationship; Osip would sing and hum his poems like a bird, and Nadezhda would commit it all to paper: great poems created outside the petty constraints of everyday existence, without any security for tomorrow.

Mandelstam was not part of the circle of writers who stayed loyal to the Soviet regime. He was repeatedly arrested on account of his friendship with many writers who had emigrated or been executed.

But, to the dismay of his wife and friends, he made the situation worse – as if deliberately. He got into disagreements with significant and insignificant writers; he defiantly resigned from the Moscow Writers' Union and eventually sealed his fate by writing a short, sarcastic poem about Stalin.

Towards the end of her life, Nadezhda Mandelstam settled on the outskirts of Moscow. Underground intellectuals and foreign Slavists would gather in her apartment, and this was where she wrote her three memoirs.

They were biting, subjective and an attempt

to settle old scores. Her memoirs were published abroad, where they sparked a

furore: nobody had written so directly and accurately about what Russian

intellectuals had endured under Stalin. However, above all else, in writing

these books Nadezhda was keeping her husband's memory alive. The majority of

his poems were only published because of her.

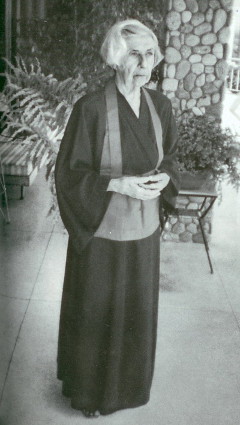

Elena Bulgakov

Elena and Mikhail Bulgakov. Source: Personal archive

In 1961, Mikhail Bulgakov's 67-year-old widow was approached by a young scholar who was studying her husband’s work. Elena was initially distrustful of the researcher, but she soon gave him the manuscript of a novel that the author had written in the last years of his life. And so, 20 years after Bulgakov's death, “Master and Margarita”rbth was discovered.

It would go on to become one of the most famous Russian novels of the 20th century. Elena – Bulgakov's third and last wife – typed up his books herself from his dictation. What is more, the character of Margarita is based on her.

There is an apocryphal story that Count Alexei Tolstoy told Bulgakov that it was necessary to get married three times. Therein lay the key to literary success, apparently, although the count himself was married four times.

There is another story that a gypsy fortune teller approached Bulgakov on the street in Kiev and predicted he would marry three times. The writer himself related how Elena asked him to tie up a strap on her clothes when they first met. In this way she “tied” him to her for the rest of his life. They both believed that their union was predetermined.

Elena's marriage to Bulgakov was also her third. She left an influential and wealthy military official to be with him, replacing comfort and security for the uncertain fate of being married to an out-of-favor writer.

Despite the fact that Stalin had loved his play “Days of The Turbins,” Bulgakov’s work was no longer printed or put on stage after 1930. He tried to leave the country, but his request was denied. He wrote his great novel full in the knowledge that it would never be published during his lifetime.

Elena edited his manuscripts, made arrangements with theaters, and kept a detailed diary of her life with the writer. “I'm doing everything in my power so that not one line should be forgotten. ... It is the purpose, the very meaning of my life. I promised him a great deal before he died, and I believe that I will manage to do all of it,” Elena confided to Bulgakov's brother, who was also a writer.

It was a difficult life. However, they didn't argue once in the 10 years they spent together. Elena wrote: “Despite the fact that there were dark moments, absolutely terrible moments, there was no melancholy, but there was horror at the thought of a failed literary life. If you tried to tell me that we had a tragic life, I would tell you not at all - not for one second! It was the most wonderful and happiest life that you could possibly wish for.”

Marina Malich

Daniil Kharms' poetry was a staple for children in the Soviet Union, as it was officially approved. Sometimes, though, these poems were printed without any indication who had written them – even selling tens of thousands of copies with the only credit going to “Anonymous.”

|

| Marina Malich was able to save her husband's work after his death. Source: d-harms.ru. |

In the meantime, this author, poet, and prose writer – an eccentric and a dandy who was one of the first Russian absurdists – died of starvation in an insane asylum during the blockade of Leningrad. None of his adult works were published during his lifetime. To the very end, Kharms had a companion and supporter in his wife, Marina Malich, whose life was no less fantastic than her husband's surreal stories.

They met as follows: “At the threshold stood a tall, strangely dressed young man in a cap with a visor. He was in a checked jacket, trousers, and golf socks. He had a heavy stick and a big ring on his finger,” Marina recalled. The two were married less than a year after their first meeting. They did not have a wedding, as they had barely enough money to live on.

Kharms occupied part of a room within a communal apartment. He had already survived arrest and exile and was blacklisted by the government. His books had stopped being published, but he worked every day, writing for children's magazines and translating.

Marina and Daniil lived a very cheerful life. At times they would wake up in the middle of the night and paint the stove pink, or they would go to catch rats in the apartment – although, as they knew, there were no rats there at all.

When there was money, they went to the Philharmonic or bought wine and went for a picnic. Kharms played the harmonica for his wife while they were at home – he had a perfect ear for music. He devoted some of his humorous verses to her, in which he called her “Fefyulka.”

In August 1941, one of Kharms’ friends denounced him. She was also close to Anna Akhmatova, who was apparently unaware that she had an informer in her circle. On August 23, 1941, Kharms was arrested and sent to a prison psychiatric hospital. Mentally ill patients were due to be evacuated from the blockaded city, but Kharms did not survive long enough: he died of starvation in February 1942.

Marina managed to evacuate to the provinces, but she was captured by the Germans and sent to Germany to work as forced labor. She no longer wanted to return to Russia, as she could not forgive the Soviet regime for Daniil’s death. Marina lived in France, before moving to Venezuela, where she ran a bookstore with her third husband. She eventually died in the United States.

After Kharms’ death, when the Germans had already started bombing Leningrad, Marina and her friend, the writer Yakov Druskin, returned to the poet's former apartment. It had been destroyed by the bombs, but they managed to find a suitcase full of manuscripts, which Druskin took with him when he was evacuated.

Hence, Marina was able to save her husband's work after his death, although it was only published in Russia during perestroika. Kharms' writing has since taken its place among the classics of Russian literature.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox