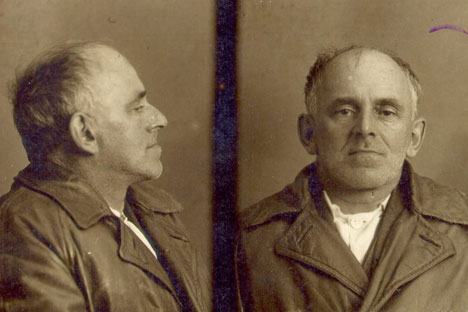

The last picture of Osip Mandelstam... Taken by NKVD. Source: Archive photo

In October 1938 Osip Mandelstam sent his final letter to his brother, Alexander. The poet was being held in a transit camp near Vtoraya Rechka railroad station – in present-day Vladivostok – and seemed to sense that the end was near: “My health is very bad, I'm extremely exhausted and thin, almost unrecognizable, but I don't know whether there's any sense in sending clothes, food and money. You can try all the same, though. I'm very cold without proper clothes.”

From the very start of Bolshevik rule, Mandelstam lived with the firm belief that he would be locked up sooner or later – at a minimum. He was strongly opposed to the official literature of the time, writing poetry that was extraordinary in its freedom. He detested imitation and censorship and made no effort whatsoever to pretend that he was loyal, even though this could have drastically improved life for him and his wife. For Mandelstam, compromising his beliefs in such a way was simply out of the question.

“It is not poetry, it is suicide”

In November 1933, Mandelstam finally launched a stinging attack on Stalin himself in a poem that he recited to several friends and never committed to paper: “His unwieldy fingers are greasy like worms. / His words are as staunch as the weights made of lead. / Like roaches his whiskers lengthen in laugh. / And teasingly shine, his polished boot-flaps.” The writer Boris Pasternak was one of those friends Mandelstam chose to hear these lines. When the poet had finished speaking, Pasternak said: “What you just read … is not poetry, it is suicide. You didn’t read it to me, I didn’t hear it, and I beg you not to read this to anyone.” This advice fell on deaf ears, and Mandelstam was arrested for the first time in May 1934.

News of the arrest was met with concern by a number of famous writers, including Pasternak, who received a notorious phone call from Stalin, of which there are more than 12 known versions. “He is your friend isn't he?” the party leader asked, referring to Mandelstam. Pasternak was flustered and didn't know how to respond. “But he’s a master, isn’t he? Is he a master of his art?” Stalin pressed on. “This does not matter,” Pasternak replied finally. “Why are we talking about Mandelstam and only Mandelstam? I've wanted to meet you for a long time and have a serious discussion.”

“What about?” Stalin asked.

“About life and death,” Pasternak answered.

Stalin hung up without replying.

Apparently Pasternak was so utterly terrified by Stalin's phone call that he was unable to petition him on his friend's behalf. However, Nikolai Bukharin, an old Bolshevik, did defend the poet, and it was thanks to his influence that Mandelstam's sentence was lessened.

Mandelstam was exiled with his wife to Cherdyn. The poet was suffering from intense mental strain as a result of being held in prison and was admitted to hospital, where he tried to end his life by jumping out of a window. After this suicide attempt, his sentence was commuted to exile in Voronezh for three years, which ended in 1937 when he returned to Moscow for the last time.

When Bukharin was arrested and subsequently executed in the spring of 1938, Mandelstam lost his last defender among the party officials. Soon afterward, Stavsky, the secretary of the Union of Writers, invited him to spend time at a health resort in Samatikha, Moscow region. On the face of it, this was a way of treating his chronic health problems, but Nadezhda, the poet's wife, always believed it was a deliberate trap that had been set with Stavsky's collaboration: it was much easier to arrest Mandelstam while he was at the health resort than follow him and his wife, who were constantly moving between different friends' apartments.

When Mandelstam's time finally came one night in May, he was taken away so hastily that he didn't even have time to put on his jacket. Nadezhda never saw her husband again: Osip had been sent to a camp in the region of the Kolyma river in northeastern Siberia. He never made it, dying instead in a secret transit camp called Vladperpunkt – an abbreviation of the Russian for Vladivostok Transit Point.

“The stone will be my last book …”

The exact circumstances of the poet’s death were a mystery for a long time. It was only years later that Nadezhda got to speak to a few people who were in the same camp as Osip and knew him during his last days. The Russian scholar Pavel Nerler recently unearthed additional information in the archives.

Mandelstam and his fellow convicts reached Vladivostok in October 1938, where they were placed in barracks. By this point the great poet was extremely exhausted and paranoid: he refused to eat his camp rations, fearing that he might be poisoned. He was so weak that he was not put to work, and he spent his days wandering through the camp. Other prisoners realized that he was a world-renowned poet, and there were some who protected and helped him. He even made friends with a group of high-profile criminals who knew his poems. They invited him to their barracks to read poetry and treated him to white bread and canned stew – unbelievable delicacies in such a camp.

As well as reading his work, Mandelstam constantly composed new poems, memorizing or writing them down on a tiny sheet of paper. Apart from individual lines that his fellow prisoners remembered, the rest of what he produced then has been lost.

The poet's mental health began gradually deteriorating as the harsh conditions took their toll. In his last weeks he was prepared to read his ill-fated poem about Stalin in exchange for just half of a day’s ration, but the other convicts shooed him away.

One day, Mandelstam volunteered to help one of his friends carry stones to a construction site. During a break, Mandelstam said, “My first book was called 'The Stone,' and the stone will be my last book.”

In December, the camp was struck by a typhus epidemic. After three weeks of quarantine, the convicts were made to stand naked in a freezing (-4 F) barracks while their clothes were treated with chemicals in a special chamber to eliminate lice and bed-bugs. The emaciated poet couldn’t bear these conditions, and he collapsed on the floor. He was taken away presumed dead but survived for another day before dying in the camp hospital.

On Feb. 1, 1939, a package that Nadezhda had sent to Osip was returned to her. She was informed rather bluntly by the post office attendant that it could not be delivered as "the recipient is dead." However, Nadezhda only received her husband's death certificate in the summer of 1940, and considered it a grim privilege – at the time, relatives of political prisoners were never informed of their deaths. The certificate read that Osip Mandelstam had died of heart failure on Dec. 27, 1938, at the age of 47.

After Mandelstam’s death, his body was dumped in a mass grave, and its exact location was not known for many years. What is more, it was only in 1998, 60 years after his death, that the first monument to the poet was put up in Vladivostok, near the site of the transit camp where his life came to such a sudden and undeserved end.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox