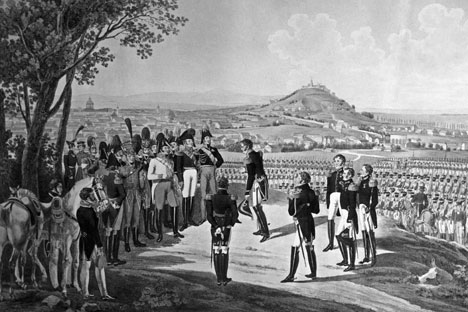

A reproduction of the drawing "Paris Surrenders on March 31, 1814 as the Russian Army pursues its 1813-1814 foreign campaigns." Source: RIA Novosti

On November 5, 1812, a wounded French general was brought to his army’s hospital in the Smolensk region village of Krasnoye. The surgeons were not overly surprised to treat such a high-ranking officer - eight French generals had died at the Battle of Borodino alone just a few months earlier. But they were startled to find the brightly colored plume of an arrow shaft protruding from the wound.

The general had fallen victim to the Kalmyk cavalry, irregular Russian Army units of horsemen from the Lower Volga steppes.

Small in stature, fearsome in reputation, these fighters were the direct descendants of the dreaded Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan, and were still largely clad and armed like their forefathers.

Dressed in colored robes and wearing shaggy fur hats with flying ponytails, their appearance on the battlefields of 1812 struck terror into the French soldiers, who dubbed them ‘hell’s devils’.

Despite the archaic nature of their equipment, it still proved effective in combat. The Kalmyk bow was a formidable weapon, wrapped in horsehair and birch bark against the damp. The animal tendon bowstring could fire an arrow about 550 yards, a range the smooth-bored infantry rifles could scarcely reach with accuracy.

The Kalmyks’ bows could also find the narrow gap between the armor plates of the French cuirassiers. Their sharp shooting at the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig in 1813 even earned them a second nickname of ‘Oriental cupids’ among the French.

The horsemen were mainly used for reconnaissance, conducting vanguard skirmishes and guerrilla raids. However, the steppe warriors also showed their mettle in head-on clashes with French infantry.

In the Battle of Fère-Champenoise in 1814, a Kalmyk cavalry regiment routed an entire square of French infantry, capturing around 1,000 soldiers and officers.

Fighting alongside the Kalmyks were Bashkir riders from the Ural steppes, who confounded the French with hitherto unseen tactics.

First, the horsemen would spend hours circling the enemy and showering them with arrows, often annihilating the French units.

As one French officer recalled, “They flew around our troops like a swarm of wasps, darting in on all sides. It was tough keeping up with them, and the attacks came again and again as the barbarians surrounded our squadrons, firing clouds of arrows to their war cries.”

In direct assaults, a rider would move his quiver onto his chest, load his bow with two arrows and clamp two more between his teeth. Riding to within 40 paces of the enemy he fired all four in quick succession and then took the lance strapped to the side of his mount and finished with a charge. In moments, he could hit up to five enemy soldiers.

Stunned by the impact of such ancient fighting techniques, the French forces told stories as they retreated from Russia about wild beasts in human form who ate the flesh of slain enemies.

But instead of bloodthirsty savages, the inhabitants of occupied German and French cities were surprised when the advancing steppe riders greeted them amicably and showed them their clothes and weapons.

In the German city of Weimar, the Bashkirs were met by the great poet Goethe. The elderly German made such an impression on one Bashkir commander that he gave him his bow and arrows. Many years later, Goethe was still proudly showing guests his rare gift.

But when the Russian Army reached Paris in March 1814, the defending French garrison saw a terrifying sight as they prepared for a last-ditch defense of the city.

Using the cavalry’s chilling reputation that had been instilled in the population by Napoleon’s retreating armies, the Russian command had 500 Kalmyks strip to the waist and smear themselves with animal blood. They then rode bareback towards the walls of Paris, driving herds of baggage camels before them in huge clouds of dust.

The psychological effect was devastating, and visualizing the horrors of defeat at the hands of this blood-smeared horde, the defenders facing them surrendered unconditionally.

On March 30, Russian Army Kalmyk units entered Paris and pitched their camp at the Champs-Élysées.

The site was duly converted into a huge racing ground where the Asian riders awed the Parisians with their horsemanship, showcasing the ancient skills that could still swing battles and wars.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox