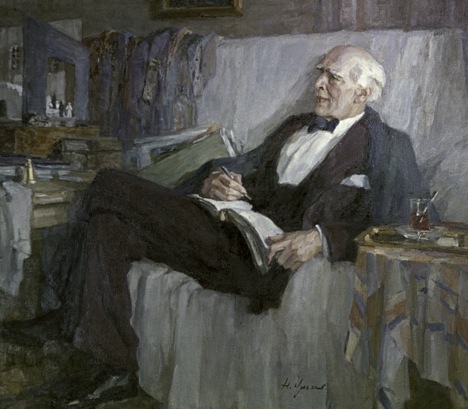

Nikolai Ulyanov "Stanislavsky at Work" (1977). Source: RIA Novosti

The theatrical “revolution” waged in the early 20th century by Konstantin Stanislavsky is often described in terms of transforming theatre “from buffoonery” into high-class art.

Stanislavsky’s theatre and his famous “system” were born as a contrast to the private theatre company that was spreading in Russia in the 19th century. The director aspired “to cleanse art of all impurity” and to create a temple from theatre. Instead of a vulgar “theatre of barmen” with popular artists, Stanislavsky had a well-functioning ensemble with strict discipline and a dictatorial director. Instead of primitive short-lived plays, there were world classics and contemporary dramas. Stanislavsky strove to raise the acting profession to the status of high art, and he and his students dreamed of creating something like a “spiritual order of artists.”

The actor’s ‘craft,’ imitating heroes’ experiences by using practiced techniques, was unacceptable to Stanislavsky. Such “art of representation” was untruthful and unable to arouse a response in the audience.

But how could one get the actor himself to believe in the nonexistent and convince the audience of it?

Stanislavsky insisted that genuine acting mastery had to be based on “experiencing the role.” “Constraint and the imposition of the alien will not disappear until the artist transforms what is imposed into something of his own. The ‘system’ helps this process,” Stanislavsky wrote. “The ‘system’ can force one to believe in the nonexistent. And where there is truth and belief, there is genuine, productive, desirable action, and there is experience, and the subconscious, and creative activity, and art.”

Konstantin Stanislavsky reurns after a 1926 guest tour of Europe and the U.S. Source: RIA Novosti

In the book An Actor Prepares, Stanislavsky wrote that people are born with this ability to create, with this “system” inside themselves. “Creativity is our natural urge. . . . But, surprisingly, when we step onstage, we lose what nature has given us, and along with the creativity we start to theatricalise, close up, play softly and represent.”

According to Stanislavsky, to genuinely “feel,” to experience the life of an imaginary person in all its fullness while preparing a role, is something an actor cannot do without involving in the creative process his own “nature,” his genuine “I”—that is, his subconscious. It is thanks to this subconscious—aside from the will—that, consciously surrendering to what is already in him, an actor can learn to live the life of the role, not noticing how he is feeling and not thinking about what he is doing. And then everything will “emerge of its own accord.”

Apparently, in looking for his “system,” his unique directorial path, Stanislavsky concluded that there was a need for serious study and a use in the actor’s work of mechanisms that were later dubbed “psycho-technical.” With them, the actor could consciously act on his own subconscious, achieve strictly defined states of consciousness in order to reach the fullness of the “experience” of the role and to know how to direct key psychic processes, including attention (concentration and switching) and images (in the imagination and perception).

It was the search for the “key” and technique of the conscious work of the actor on his own subconscious that drew Stanislavsky’s attention to yoga. After discovering the congruence between its principles regarding the psycho-technique of the “inner work” of a person on himself and his own perspectives on the nature of the actor’s creativity, Stanislavsky started using the approaches and terminology of yoga in his own practice.

Stanislavsky apparently became acquainted with the study of yoga in 1911. Actress Nadezhda Smirnova recalled that in one discussion in which Stanislavsky was sharing his thoughts on his nascent “system,” his son’s tutor, a medical student named Nikolay Demidov, said, “Why do you need to come up with your own exercises and names for what has already long had a name? Read ‘Hatha Yoga’ and ‘Raja Yoga.’ You’ll find them interesting because a lot of your ideas coincide with what’s written in them.”

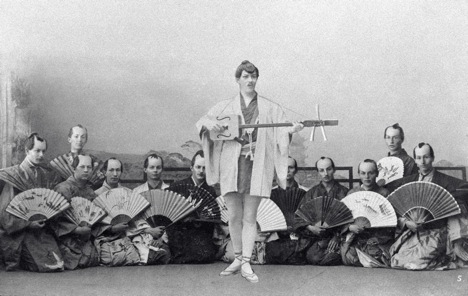

Konstantin Stanislavsky (center) as Mikado Nanki-Pu in Sullivan's operetta Mikado. Source: RIA Novosti

Stanislavsky indeed got hold of Ramacharaka’s book Hatha Yoga: The Yogi Philosophy of Physical Well-Being and later Raja Yoga. Mental Development, and studied them closely. The yogi Ramacharaka was a pseudonym of the American William Atkinson, who became interested in Indian philosophical systems in the early 1890s and over the course of 30 years wrote more than 100 books, which were for many people—including Stanislavsky—an introduction to the systematic learning of yoga.

It is obvious that after 1911 yoga permanently entered the director’s arsenal and became an integral component of the actors’ training in Stanislavsky’s First Studio, which was organized under the auspices of the MAT (Moscow Art Theatre).

A studio actress, Elena Polyakova, wrote in her memoirs that acting “improvisations were alternated with readings from Hatha Yoga.” Stanislavsky’s acting students kept the book on Hatha yoga on hand, and it was required reading. Evgeny Vakhtangov, a renowned Russian director who was a student of Stanislavsky’s, wrote in a letter to the studio actors in 1915, “And another request. Take 1 rouble to the box office. Buy Ramacharaka’s‘Hatha Yoga.’ Give it to Vera Exemplyarskaya [a student in the studio] from me. Make her read it carefully, and this summer make her do exercises from the part on breathing and ‘prana.’”

Vera Solovyeva, an actress in the studio, recalled, “We worked a great deal on concentration. It was called ‘To get into the circle.’ We imagined a circle around us and sent ‘prana’ rays of communion into the space and to each other. Stanislavski said ‘send the prana there—I want to reach through the tip of my finger—to God—the sky—or, later on, my partner. I believe in my inner energy and I give it out—I spread it.”

The experience of using yoga practice in the First Studio stayed with many of the actors all their lives and was passed down to students. Mikhail Chekhov, a famous actor and student of Stanislavsky’s, wrote that “the philosophy of yogis was perceived by me quite objectively, . . . without any inner resistance.” He considered the “rays” of prana one of the most important devices of the actor’s psycho-technique.

The writer used Sergei Tcherkasski’s 'Stanislavsky and Yoga' as the main point of reference.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox