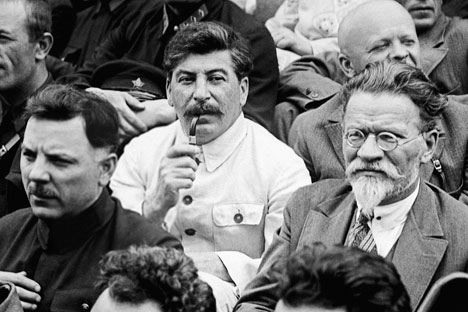

Joseph Stalin at the First Congress of Collective Farmers, 1933. Source: RIA Novosti

Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution, had a striking and paradoxical image. It combined his small height, a bald patch, a speaking impediment (Lenin could not pronounce the Russian‘r’ sound), his legendary flat cap, brisk walk and heightened emotions.

Most of the monuments that until recently graced the central squares of every city and town up and down the country depict him in motion, with his favourite flat cap either on his head or crumpled in his hand.

Stalin's image was the complete opposite. After the chaos of the civil war, the country needed stability and a leader who would exude strength, confidence, dependability, and unbreakable power.

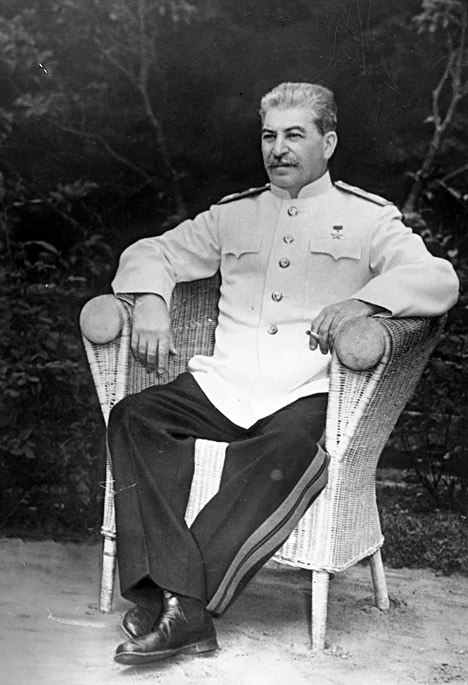

Stalin at the Potsdam conference, 1945. Source: RIA Novosti

Stalin's ethnically South Caucasian features and his unhurried manner were just what the doctor ordered. Here is an excerpt from memoirs by the first Soviet oil industry minister in Stalin's government, Nikolai Baybakov: "I entered and stopped; there was Stalin, the supreme commander, standing, albeit with his back to me. I approached him, not daring to cough. I looked at him, at what he looked like: He was dressed in a gray tunic and soft-leather boots, very modestly for the head of state…"

Soldiers of the Revolution and children of the Civil War

From the years of the revolution until the middle of World War II, Stalin's preferred dress was a military tunic made of top-quality fabrics and trousers tucked inside soft-leather Caucasian boots.

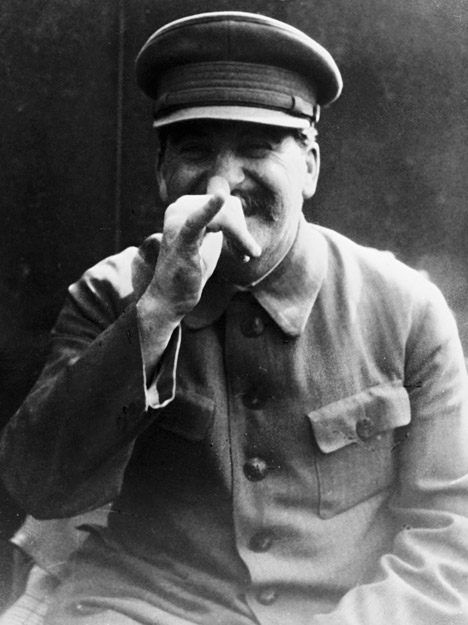

Stalin, 1930. Source: RIA Novosti

For years he wore an ordinary soldier's coat when outdoors, until it became worn out.

Military tunics became popular in Russia during the First World War, when no strict uniforms were enforced and many officers, having seen what British and French officers were wearing, began to copy that design. The British Army had two types of tunic: a more formal one, for officers, worn with a shirt and tie, and a looser and more comfortable one, for soldiers, worn without a tie. It is the latter version that became particularly popular with senior Red Army commanders.

Artyom Sergeyev, the son of a close friend and associate of Stalin's, recalled in an interview with Yekaterina Glushik titled "Conversations about Stalin" (published in the Zavtra newspaper in 2006): "One day Stalin came home and saw a new coat handing on the peg. Seeing it, he asked: 'And where is my old coat?' To which he was told that it was already gone. He became very angry: 'For public money one could get a new coat every week. I could have worn the old one for a whole more year and then you could ask me if I need a new one.' He was seriously put out."

There was a tacit agreement between members of the Communist Party to adhere to the same style of dress, based on a military tunic or a soldier's shirt.

It was not only for ideological reasons that "soldiers of the Revolution", as party functionaries called themselves at the time, preferred semi-military clothes.

Most of them, prior to moving to government offices, had spent time fighting in the First World War, then taking part in the Revolution and then commanding the Red Army in the Civil War.

They felt more comfortable in a soldier's shirt than they would have in any civilian clothes.

From 1938 onwards, suits for the country's leaders, including some of Stalin's tunics, were made by the central sewing workshop for designing new uniforms for Red Army generals, which exists still under the name of the open joint-stock company Central Experimental Sewing Shop 43. Stalin personally approved all new designs of military uniforms, all the way down to the buttons.

Birth of the Imperial style

While at home, he preferred to dress simply. Artyom Sergeyev recalls: "At home, he wore canvas pants and a linen jacket, which he sometimes took off and remained in a cotton shirt, akin to that of a soldier. I have never seen him wearing a civilian suit. While on holiday, he would wear a linen suit with the jacket buttoned up, which he would sometimes unbutton to reveal a white shirt underneath."

The Yalta Conference of Allied leaders (February 4-11, 1945). Source: ITAr-TASS

When it came to headwear, Stalin preferred a peaked cap with a small and even crown. Each of his caps was handmade once the previous one became worn out. If, when trying a new cap, Stalin found something wrong, he simply continued to wear the old one.

After Stalin was given the titles of Marshal of the Soviet Union and Generalissimo, designers' flights of fancy came up against the Soviet leader's minimalist tastes.

The original version of the uniform – aquamarine in color, lavishly embroidered with golden thread and essentially based on Russian officers' uniforms of the early 19th century – was rejected at the first presentation and sent to a museum, where it remains to this day.

Instead, a simple light-gray tunic was made, with a turndown collar (since Stalin found the originally proposed band collar uncomfortable), the classic four pockets and marshal's epaulettes.

The trousers had trouser stripes, and the whole uniform looked quite impressive. That was how his fascination with the Imperial style was born: He found it reserved and striking at the same time, austere and grand.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox