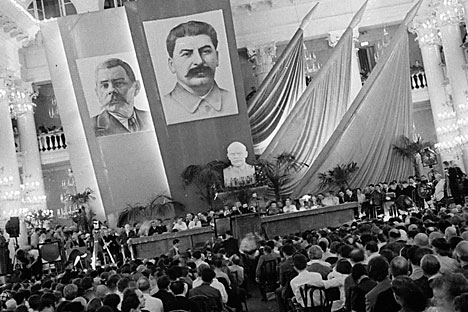

Delegates of the First Congress of Soviet Writers in the Pillar Hall of the House of Unions in Moscow, on August 1934. Source: RIA Novosti

At the beginning of the 1930s Stalin decided to create unions representing every different creative profession. The official reason, as voiced by writer Maxim Gorky, was to allow greater unity of creative vision and a harmony between the individual's creative aims and the overall “creative working energies of the country.”

This idea of uniting for one great aim – furthering the revolution – was just a smokescreen, however. In reality, these organizations were a means for Stalin to achieve his political aims. He realized that he could easily control and censor single unions and force them to produce the kind of art that he approved of.

A lavish setting for controversy

The early 1930s were tough years for the Soviet economy, but the First Congress had a budget of 1.2 million rubles – equivalent to the annual salary of 754 factory workers – and was attended by 591 delegates from 52 countries. The government covered all the delegates' expenses and provided a full program of excursions. The location was the Pillar Hall of the House of Unions, which was decked out with portraits of famous Russian writers and poets.

Attendees at the congress included Boris Pasternak, the foremost Soviet poet of the time, the “Red Count” Alexei Tolstoy, a nobleman who adjusted to the demands of Soviet power, future Nobel laureate Mikhail Sholokhov, and leading children's author Korney Chukovsky.

Maxim Gorky gave a keynote lecture to close the event on September 1. He spoke about education, about uniting writers from the USSR's different republics, and laid out his vision for the development of Soviet literature. Gorky placed a great deal of responsibility on Soviet writers, describing them as “the great present and future of the Land of the Soviets.”

Gorky also placed heavy emphasis on politics. He criticized bourgeois life, attacked fascism, quoted Stalin and appealed directly to him, ending his speech by glorifying the leader. His words drew a mixed reaction: some writers agreed, while others criticized him for playing up to the government.

Nikolai Bukharin's speech also caused a stir. Bukharin, the editor-in-chief of the popular Isvestia newspaper, was an old Bolshevik who had been kicked out of the Politburo by Stalin a few years earlier. He spoke about Soviet poetry for three hours, referencing taboo Silver Age poets such as Nikolai Gumilev – who had been executed in 1921 – Alexander Blok and Andrei Bely. Considering that the congress was designed to further orthodox writing, this speech was not well-advised and probably hastened his downfall. Bukharin was executed a few years later.

Hypocrisy and insincerity

Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's right-hand man, tried to convince the leader that everyone, including skeptics, had “liked the congress very much,” but a cursory look at the writers' correspondence – which the NKVD intercepted as part of their broad spying program – showed Stalin that this wasn't the case.

The secretary of the then Union of Writers, Alexander Scherbakov, wrote: “I could stand that only for half an hour. I felt sick and left.” Writer Mikhail Prishvin noted that the speeches were “unbearably dull,” while Isaak Babel felt that it was a “requiem for literature.” Boris Pasternak said he was disappointed that so much time was given over to politics rather than solving issues in literature, but he still found some of the arguments and debates interesting.

In a scandal that was completely hushed up, the NKVD found a leaflet written by a group of anonymous Russian writers. Addressed to the foreign guests, it outlined the “supreme lie” that was both the congress and the Soviet Union and lamented the fact that there had been a total lack of free speech in the country for almost two decades. “The USSR's network of informers is so comprehensive that even at home we often avoid speaking our minds.”

For such a massive event, the congress only made minor ripples in society. Several newspapers published transcripts of the speeches but didn't add any analysis. Many writers left Moscow after the event, going on vacation or supposedly to start work on new projects.

The lack of discussion and literary news led Zhdanov to complain that it seemed like the participants had taken a vow of silence, and the Party even published a decree that there should be more press coverage of the event. With hindsight, it seems likely that many writers simply didn't want to lie about their true opinion of the congress or put themselves at great risk by criticizing a government-approved event.

A lasting impact

The congress wasn't all negative. It gave young foreign writers the chance to visit the Soviet Union and gave exposure to writers from the Soviet republics. Many such authors were translated into Russian for the first time and gained a new readership. A notable success at the congress was Dagestani poet Suleiman Stalski, who Gorky introduced as “the Homer of the 20th century.”

The congress marked a turning point in Russian literature. It formulated the principles of a new style, socialist realism, which, in essence, meant glorifying the Communist Party and nothing else. Originally, the congress was supposed to take place every three years, but it was postponed many times. In fact, the next event was in 1954, after Stalin's death. This was no coincidence: one congress was enough for Stalin to achieve his goal of bringing writers to heel.

A third of the original delegates died in the 20 years between the first and second congresses. Some died from natural causes, and others were killed during the war. However, the overwhelming majority were executed or died in prison or labor camps.

There were only eight congresses between 1934 and 1986, and they increasingly became formal events with almost no influence on Soviet culture. The First Congress was unique in its own way – it was the first and last successful attempt to unite all the writers of one country.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox