Mikhail Shemyakin. Sketch for "Crime and Punishment" ballet. Source: mihfond.ru

A literate murderer

What unites Cervantes’s “Don Quixote” and Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment”? Both are centered on the perception of reality through literature. As translator Oliver Ready argues, Raskolnikov, the anti-hero of “Crime and Punishment,” is most at home in the world of words, whether books, newspapers or letters from acquaintances and relatives that he analyses like a literary critic or a detective. He is not just a student and a murderer – he is a reader and a writer, whose literary debut, an article about crime, is one of the great missing clues in the novel.

|

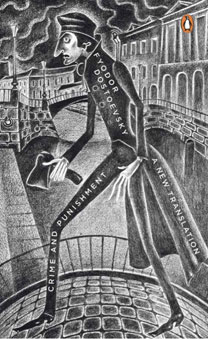

| Fyodor Dostoevsky 'Crime and Punishment.' Translated by Oliver Ready. Source: Amazon.com |

The very fact that Raskolnikov is a man of letters is what makes it so important to get as close to the original as a translation allows. Out this year in Penguin Classics, Oliver Ready’s new translation of Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” aims to preserve the original's troubled and polyphonic narrative, and the varying language and vocabulary of its different characters.

In his translation, Ready, a research fellow in Russian society and culture at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, chose not to use 19th century English or contemporary language. Instead, his vocabulary belongs somewhere in the middle of the 20th century, and he tries to avoid words that appeared after the 1960s. This makes the new translation's language “modern, but not contemporary.”

Back to pen and paper

The translation has been five years in the making, and to get closer to Dostoevsky’s own approach, Ready worked in longhand. “In fact, I wrote out every sentence – it was a kind of experiment, I suppose. I did this to get away from the computer and in the hope that the translation would come out better if I wasn’t tempted to edit myself after every phrase. That's the curse of Word,” Ready explains. “In reality, the laptop remained switched on for much of the time while I consulted online dictionaries and other resources, but still, I found the process of writing by hand helped my concentration and nerves.”

Several earlier translations tended to smooth over Dostoevsky’s stylistic peculiarities, robbing the novel of the unique, jagged tone and nervous repetitions that best represent Raskolnikov’s anxious state. Ready sought to preserve these lexical peculiarities of Dostoevsky’s language in his own work, while also trying to maintain the novel’s hypnotic and compelling power. In doing so, he inevitably stumbled on some unique features of Russian that are very hard to reproduce in English.

“All those particles and adverbs, often denoting elusive emotions and emphasis rather than meaning – dazhe (even), kak by (as if), kak-nibud (somehow); all those deliberate – and accidental – repetitions; all those short, apparently simple words that actually have a multitude of meanings. Raskolnikov says his heart is zloe. Evil? Spiteful? Nasty? For me, none of these. I chose something different, on the evidence of his character throughout the novel – as I understand it.”

An ongoing legacy

Completed in 1866, “Crime and Punishment” immediately received great acclaim from readers and critics. Its first partial translation (into French) appeared the same year, and by the end of the 19th century, the novel had been translated into German, Polish, Italian and some other European languages. The novel’s impact on world literature was noticeable through the whole 20th century, and it is still relevant today. “The preoccupations with the inauthenticity and virtuality of his own existence that bedevil Raskolnikov are now shared by many young people across the world,” Ready comments.

“Raskolnikov’s sense of impotence, of not being able to turn words into deeds, is as dangerous now as it ever was. There are, of course, many other themes that have lost none of their relevance: the human costs of capitalism, child abuse, broken families and alcoholism, for example. These are some of the starting points, in fact, for Rowan Williams’s recent book on Dostoevsky’s fiction (2008), written when Dr Williams was still Archbishop of Canterbury.”

Dostoevsky’s work is widely considered to be a representation of the “mystery of the Russian soul,” and he is often seen as the most “Russian” of all Russian writers. But the popularity of his novels around the world suggests that there is something very universal about Dostoevsky’s novels. What exactly this may be is a matter for debate. Ready feels that “the knee-jerk reaction would be to say that it is his fascination with extremes of character, of pride and humiliation. Actually, though, much of this could be found in the French and English novels that Dostoevsky devoured and even – in the case of Balzac – translated.”

According to Ready, “one thing that is typically Russian about ‘Crime and Punishment’ – or at least typical of the great Russian literary tradition – is its obsession with cultural inauthenticity, the fear that ideas and even values imported from the West, often questionable enough in themselves, can quickly become fake, cheapened and corrosive in Russia.”

Ready explains that “this anxiety is already there in Pushkin and can still be found in Russian writers today. This seems extraordinary when one considers the tremendous originality and daring of nineteenth and twentieth-century Russian literature and culture, but perhaps it was this same anxiety that, in part, made such a flourishing possible.”

Another common statement about Dostoevsky is that he can be compared to Charles Dickens. Ready, however, says that this is misleading, suggesting that there is a “chasm” between the two writers. “Of course, there are many elements of the Victorian novel in Dostoevsky,” he explains, “but Dostoevsky’s technical, linguistic and formal innovations – his extraordinary directness, his fractured mode of narration, his cacophonic catastrophes – align him more with Joyce, Faulkner, John Cowper Powys, J.M. Coetzee and a host of other modernist, or simply modern, writers.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox