Rollers on Moscow streets. Source: ITAR-TASS

Today, just as they are all over the world, jeans in Russia are an unofficial symbol of democracy in fashion, the universal choice for the young and the young at heart, as comfortable on the hips of a long-distance trucker as a university student or a DJ. Stores are stacked high with thousands of different brands and styles, from cheap Chinese denim to luxury pairs affordable only to the moneyed elite. But back in the days of the Soviet Union, quality jeans were so highly prized that people would go to extraordinary lengths to get their hands on a pair.

Soviet people were first exposed to denim when the first jeans reached the USSR in the 1950s. The official beginning of "jeans fever" could be considered to be 1957, when Moscow hosted the World Festival of Youth and Students. From then onward, jeans were perceived not just as clothes but as a symbol of everything that was missing in the USSR, mainly freedom.

You could wear anything you wanted, but if you had a real pair of jeans in your wardrobe that meant you had arrived in life. There were campaigns against wearing jeans, which were then banned, and people could even be expelled from university or fired for wearing them. However, those restrictions only made the yearning for jeans even stronger among the country’s fashion-conscious.

The first people to wear jeans in the USSR were sailors, pilots and diplomats' children. They brought jeans from abroad, often literally on them, wearing several pairs of jeans beneath some baggy trousers. Later jeans began to be associated with the hippie culture, and were decorated with patches and flared at the bottoms.

Faded jeans

The main thing that distinguished genuine jeans from counterfeit items was that real denim faded with washing. When buying a pair of jeans, people tested them with the use of a wet match. They drew it along the fabric and if the match turned blue that meant that the jeans were genuine; if not, that they were counterfeit. In fact, what distinguished true denim (from French de Nîmes, meaning ‘from the city of Nîmes’) was not poor-quality dye but the fact that in denim only the weft threads are dyed, while the warp threads remain white.

A family spending a day off on the Moskva river, 1977. Source: Soloviev / RIA Novosti

This creates denim's unique fading characteristics. The longer you wear a pair of jeans, the more faded and therefore the more valuable they become. Soviet-made jeans, of course, did not leave any marks on wet matches.

Standards did not intend the use of cheap dyes. In the meantime, underground manufacturers learnt to treat denim with dyes that easily washed out and even learnt how to artificially age jeans with the use of pumice.

Trafficking

Traffickers were the first "free market sharks" in the USSR. Soviet propaganda presented them as almost the worst enemies of the Soviet people. Trafficking in goods was punishable not only with prison but also with ostracism.

In order not to have problems with the law, instead of selling coveted goods, people often exchanged them for something that was also in short supply. Barter was not banned in the USSR (unlike foreign currency operations).

Regular customers knew traffickers by sight, while experienced traffickers ‘scanned’ crowds at markets, outside hotels and railway stations in search for prospective buyers. Many of today’s prominent Russian businessmen began their careers by trafficking in jeans.

In 1961, the traffickers Rokotov and Faibishenko were sentenced to death. One of the charges against them was "trafficking in jeans.” The echo of that story reverberates still: There is a firm in the U.S. that makes Rokotov & Fainberg jeans in their memory.

‘Boiled’ jeans

The main reason why people ‘boiled’ their jeans was the shortage of genuine items. Wearing Soviet-made jeans that refused to fade and look like foreign denim was not an option for fashionable young people. The ‘boiling’ technology was very simple and resulted in a washed-out look for your pair of jeans.

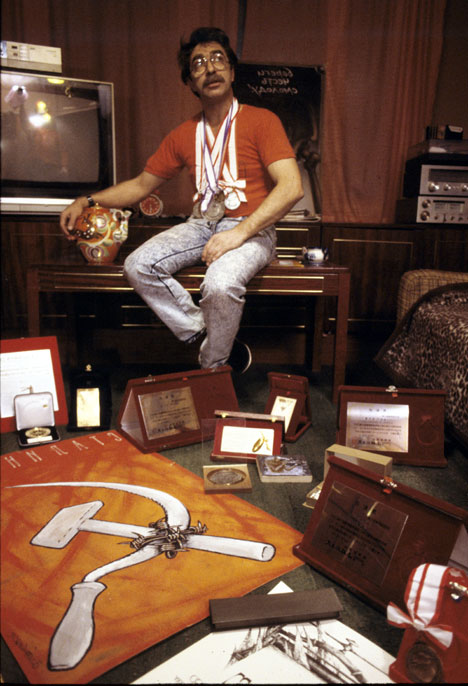

Mikhail Zlatkovsky, president of the USSR Caricature Association, in 'boiled' jeans, 1990. Source: Alexei Boitsov / RIA Novosti

This is how it was done: 1) Twist a pair of jeans and fix it with rubber bands and various clips (do not twist too much since that would create too many breaks and splotches; 2) Add bleach to warm but not yet boiling water (approx. one glass per 5 liters); 3) Put the jeans into the water and boil them for 15-20 minutes; 4) Rinse the jeans several times. P.S. Take the necessary precautions: Wear rubber gloves and open the windows.

Cult

In the final years of the USSR, the most common brand of jeans in the country was Montana. There is indeed such a label in Germany (registered in 1976), but the origins of the Soviet Montana are questioned by fashion historians.

Most probably, Montana jeans were made illegally somewhere in the south of the country and then supplied to the market. Montana's distinctive feature was how hard and unbending they were: you could literally put them in a corner.

Jeans became a usual thing for Russians now. Source: Lori / Legion Media

Other popular brands were Levis, Wrangler, and Lee. They did not come cheap, starting from 100 rubles (the standard monthly salary of a Soviet engineer). Those who did not have the money for an American pair of jeans could buy jeans made in India or Poland.

They were of inferior quality, and those who could not face the harsh reality just removed the original labels from their less than perfect jeans. In the late 1980s, the first Soviet jeans labels appeared – Tver, Vereya – but their quality left much to be desired. They were not even made of denim. Having said that, those who could sew often made quite decent jeans at home.

First published in Russian in Russkaya Semyorka.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox