Film censorship in the Soviet Union

Ivan’s Childhood (1962) by Andrei Tarkovsky. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Andrei Zvyagintsev’s film Leviathan, which made headlines when it was selected as Russia’s nominee for this year’s Foreign Language Oscar, will soon be available in Russia in wide release. But audiences will not see the film the director intended. Leviathan is the first film released since the passage last summer of a law banning the use of curse words in media. Under the new law, officials have the right to selectively release films for showings to a wider audience. The version of Leviathan available in Russian theaters will feature dub-overs to make the film acceptable for showing under this legislation, which came into effect July 1.

Leviathan (2014) by Andrei Zvyagintsev, official trailer. Source: YouTube, PalaceFilms

Some critics and directors have argued that the new law is a step towards the kind of censorship artists fought in the Soviet Union. The current law is different from Soviet-era censorship laws, but the battles Soviet directors fought with censors are worth recalling as a cautionary tale.

The God taboo

Andrei Tarkovsky only managed to produce five films even though on average he could make a film a year. Tarkovsky spent 16 years of his career unemployed. His first film, Ivan’s Childhood (1962), which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, was mocked in the Soviet Union. It was marketed as a children’s film and only shown in the morning. Officials were upset that the film was seen as pacifistic beyond the Iron Curtain; in the heat of the Cold War, this contradicted Soviet foreign policy.

.jpg)

Ivan’s Childhood (1962) by Andrei Tarkovsky. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Each of Tarkovsky’s films was a masterpiece in world cinematography, and each film was subject to strict censorship. Soviet censors were unhappy with the excess of religious symbolism in Andrei Rublev (1966), and as a result, the film was shortened by 25 minutes. Tarkovsky was not allowed to make a film for six years following its release. Showings of The Mirror (1975) and Stalker (1979) were limited because of their complex language, and the press either gave them negative reviews or kept silent. Solaris (1972) was Tarkovsky’s only more or less successful film. Even though Soviet officials were irritated by its philosophical line and its arguments about God and cognition – and despite the fact that they demanded more than 40 changes to it – the film was still well known in the Soviet Union.

Censorship in several stages

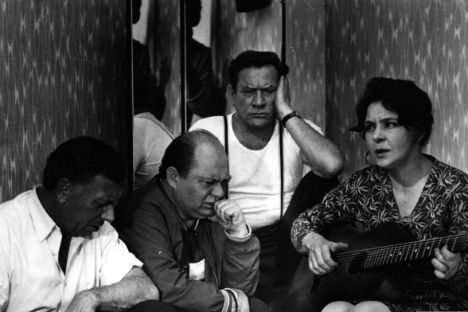

Andrei Smirnov, who directed Belarus Station (1970), a cult Soviet film about veterans, remembers the process of working with censors. "There were no clearly formulated rules. Everything depended on the particular official who said yes or no,” Smirnov said. “The Soviet State Committee for Cinematography [Goskino, which had to approve completed films] was just the final stage; censorship started on the first day of film production. At Mosfilm studios, local editors proofread the scripts, after which they were discussed by the arts council – a team of filmmakers, screenwriters and directors. And this wasn’t done without the Party Committee, the local body of the Communist Party. And of course, they closely observed the films during filming.”

Belarus Station (1970) by Andrei Smirnov. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Film critic Victor Matizen recalls the process differently. "Despite the lack of censorship instructions, you could easily determine the reasons behind the censors’ displeasure in each particular case. Let’s say the heroine of a film needed to represent all Soviet women. If, for example, she changed husbands, the censor would ask, ‘What do you want to say with this? That all Soviet women switch husbands?!’” Matizen said.

“When the film The Cranes Are Flying (1957) won an award at the Cannes Film Festival, nobody in the Soviet Union was in a hurry to honor the director Mikhail Kalatozov. In a short note about the event published in the newspaper Izvestia, not even his name was mentioned, and there was no photograph. Why? They say that then-Soviet leader Khrushchev had an extremely negative reaction to the film’s storyline – the part where the heroine replaces her lover who left for the front.”

Class consciousness

Among the most important requirements for Soviet films was that of “class struggle.” Andrei Konchalovsky’s film Siberiade (1978), which won a Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, was an attempt to reduce the complexity of life into ideological clichés. In one of the scenes, geologists who were drilling next to a village cemetery finally strike oil. But the associated gas issuing from the well causes a fire that gradually spreads to the cemetery. The villagers try to rush to the graves of their loved ones, but they are held back from fear of another explosion. A subtle vision appears on the screen – a farewell embrace between the dead and the living. Soviet officials had this to say about the poignant shots: “The symbolic fraternization between the living and the dead shall not acquire the character of a class reconciliation.”

Siberiade (1978) by Andrei Konchalovsky. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

More than anything, Goskino feared criticism of the Soviet regime. For this reason, no type of film – from a fairytale to a sci-fi epic – escaped the eye of the censors. Filmmakers were asked to make changes “to clarify class character” and “to clarify the socio-class aspect.” Such was the case with a sci-fi film proposed by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky called The Fighting Cat Returns to Hell; the censors read into the earthlings’ interfering in aliens’ internal affairs and judged it to be a promotion of the false concept of “exporting revolution.” Despite the Strugatsky brothers’ attempts to honor individual critiques, the script was not recommended for staging.

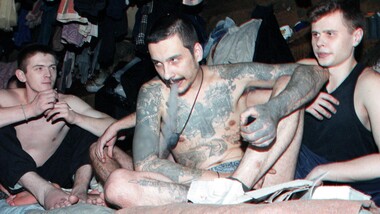

A cemetery of films

"It can be said that Soviet film fell under the scalpel of censorship. Yes, there was a scalpel, but there was also an axe,” said film critic Valery Fomin. “Censorship left an enormous cemetery of films and unfinished projects in its wake. It wasn’t enough to ban or cut; they had to punish, as well. This acquired monstrous forms of public execution.”

When director Sergei Eisenstein took on the film Bezhin Meadow in 1935, which was about the boy Pavlik Morozov who denounced his father as an enemy of the Soviet authorities, it was expected that Eisenstein would be formally fulfilling a government order. However, the director took a different route and refrained from political commentary. The final product was far from a shining example of Soviet rhetoric. As a result, the Soviet filmmaking community harassed Eisenstein almost to the brink of suicide.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox