Young Alexander Solzhenitsyn at the Ryazan-pristan railway station, 1959. Source: RG

Among the thousands of political prisoners sent to Soviet Gulags, there were many of those who belonged to creative professions – writers, poets, musicians and artists – who secretly continued with their artistic pursuits.

Doing anything creative, like drawing or keeping notes, was strictly forbidden, to say nothing of attempts to smuggle anything out of the camps. RIR has compiled a list of the most significant works of art, music and literature that were created in Soviet prison camps and miraculously survived to become known and remembered by modern generations.

24 Preludes and Fugues for the piano by Vsevolod Zaderatsky

The 24 Preludes and Fugues piano cycle was composed by Vsevolod Zaderatsky at a Gulag camp in the region of Kolyma in the Russian Far East in 1937-39. “He managed to find time and scribble his compositions on whatever scraps of paper he could find,” the composer’s son recalled.

“My father had a very neat handwriting, which helped. Sometimes guards gave him paper too because they valued him as a storyteller. He was like a TV set for them,” he said. The world premiere of the cycle took place 75 years after it was composed, at the Moscow Conservatory on Dec. 14.

Poems and plays in verse by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Solzhenitsyn wrote his world-famous One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and The Gulag Archipelago after he had served his term in the Gulag (1945-1953): While in prison, he had no opportunity to work on long prose.

Alexadner Solzhenitsyn. Searching in the labor camp. Source: RG

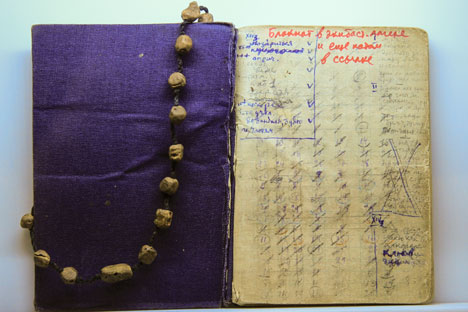

However, in the labor camp, using just small scraps of paper, he composed and learnt by heart (with the help of a rosary he had made himself) several poems and plays in verses: Dorozhenka (‘Little Road’), Plenniki (‘Prisoners’), and Pir Pobeditelei (‘Victors’ Feast’).

As Solzhenitsyn himself wrote in Part V of The Gulag Archipelago, by the end of his prison term, he held some 12,000 lines of poetry in his head. However, Solzhenitsyn decided to publish that early poetry only after he turned 80.

Solzhenitsyn's notebook. Source: RG

“Those works were my breathing, my life at the time. They helped me to survive,” he explained.

‘Kolyma Notebooks’ by Varlam Shalamov

Shalamov served two terms in prison camps, in 1929-1932 and in 1943–1951. The first was in the northern Urals, while the second, and far more horrendous, was in Kolyma.

|

| Shalamov, 1959. Source: Press photo |

It was there, in 1949, after he had managed to escape hard labor to work as a medical attendant at a hospital for inmates, that he began to write the poetry that became the foundation of the future Kolyma Notebooks.

Having read them in 1956 in samizdat, Solzhenitsyn, as he himself later recalled, “trembled as if I had met a brother.”

Boris Pasternak too had a very high opinion of Shalamov’s Kolyma Notebooks.

However, Kolyma Tales, a tough and uncompromising account of life in the camps, once again turned Shalamov into an outcast and an alien for the literary establishment.

Guillaume du Vintrais' ‘Wicked Songs’ by Yury Veinert and Yakov Kharon

Wicked Songs was a collection of 100 sonnets written in an Amur Gulag in the Far East in 1937-47 by two Moscow intellectuals in the name of a fictitious 16th-century French poet they had invented, who allegedly had been courtier to Henry II of Navarre. Strictly speaking, the sonnets themselves are not much more than an inspired hoax, a literary game prompted by the enormous popularity that the works of Alexandre Dumas and Cyrano de Bergerac enjoyed at the time.

However, given the conditions in which these daring verses, celebrating women, wine drinking and, above all, honor and freedom, were written, the literary hoax becomes a truly heroic artistic act. The mastermind of the ‘project’, Yury Veinert (the name Vintrais is an anagram of his name rendered in French spelling), died in the camps. Yakov Kharon lived till 1972 and saw the publication of Wicked Songs in his lifetime.

‘Roza Mira’ by Daniil Andreyev

The son of Russian Silver Age author Leonid Andreyev, Daniil grew up surrounded by the artistic elite of the time and was interested in mysticism from an early age. During his imprisonment in 1947–1957, he experienced an intense mystic revelation.

The experience led Andreyev to develop a religious and philosophical teaching, which is fully outlined in his main work, Roza Mira (‘Rose of the World’), which in terms of its power of persuasion and coherence was in no way inferior to William Blake’s mystical poems or Joseph Smith’s Book of Mormon.

It was only the complete blackout that Roza Mira was subjected to in the Soviet Union (the book was first published only in 1991) that prevented it from becoming the foundation for a new religion.

Pavel Florensky’s letters from the Far East and the Solovetsky Islands

The letters written by the priest Pavel Florensky to his wife and children and close friends from the moment of his arrest in 1933 until his execution in 1937 were collected and published as a book in the late 1990s.

Ruins of abandoned labor camp, Tumen, 1992. Source: TASS / Alexey Schukin

Strictly speaking, the letters are not a literary work, but the extraordinary cultural and scientific versatility of the man – he was a philosopher, a poet, a theologian, a mathematician, a biologist – was such that even his letters to his family become a work of philosophy: in effect, his testament.

Mikhail Sokolov’s miniature paintings

After the revolution, Mikhail Sokolov was one of Moscow’s leading artists, however, in the 1930s he became marginalized, since his impressionist works were not in line with the concept of socialist realism.

In 1938, he was sent to a prison camp in the Kemerovo Region, where he continued to paint taiga landscapes and portraits of his fellow inmates on small scraps of paper, sometimes candy wrappers, sending these miniature paintings to Moscow, where they were greeted with universal admiration. Sokolov’s miniature paintings from the camps now take pride of place in the art museum in his native city of Yaroslavl.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox