For four years James Hill photographed veterans at Gorky Park on Victory Day. Source: James Hill

James Hill has worked as a photographer for the New York Times in Russia for more than 20 years. Of the many photos he has taken, his portraits of veterans stand out. For four years, he photographed veterans at Gorky Park on Victory Day. In 2010, he finished his project and published a book of the portraits, which was presented at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art.

This year, James Hill's photo project, Victory Day, will be on display in London for the first time. Elena Bobrova of RBTH spoke with Hill about the project and his feelings about World War II.

|

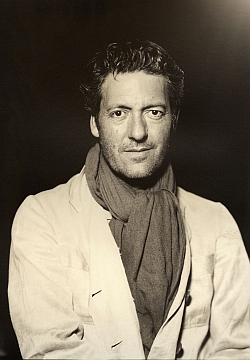

| Photographer James Hill. Source: From personal archives |

RBTH: How did your Victory Day project start? Did the New York Times commission this work?

James Hill: It was my own initiative, but back in 2006, the New York Times paid for the first step of the project and for the film processing and scanning. But the rest of the time, I was doing it for myself.

There were two particular reasons for my project: I was very interested in the women who fought in World War II because this was the greatest mobilization during wartime – over 500,000 women in the Soviet Union. They served as nurses, radio operators, pilots and even snipers. In 2006, I only took photos of women.

But then I saw very handsome old sailors and pilots and felt that I need to come back and work more.

The second reason that motivated me: I came to the Soviet Union for the first time in 1991 and as I lived on and off here, I felt that veterans weren’t seen as individuals. They were more like icons in the Soviet and post-Soviet mentality. When I saw portraits of them, I always saw heroes. Of course they were not glamorized, but somehow polished.

Because every Russian felt such respect towards them, it was hard for Russian photographers to work on this issue. There was no room for subjectivity. And if somebody would do it differently, it could be seen as a lack of respect.

As a foreigner, I felt I could add something to the way veterans are seen in Russia.

RBTH: How did the process work?

J. H.: Besides two photo assistants, I had two assistants who were trying to grab people from the crowd. They came up and asked veterans if they would like to participate. The main attraction for them was the fact I was giving away Polaroid photos immediately. In the end, I had about 500 shots of veterans in total.

Some of them were coming every year and participated again. I recall a very precise moment when one woman whom I photographed in 2006 didn’t show up for three years, but then she came in 2009. It was quite emotional to see her again, because I was afraid she had died.

RBTH: Will you go to Gorky Park this year?

J. H.: I don’t know. I might go to the parade and to Gorky Park, but it’s a bit difficult for me to go back. I’m done with the project, but the exhibit is alive. It will be shown this year in London from May 7 in Pushkin House and in Kazan, opening on the 8th.

Ten big prints were taken to the permanent collection of the Pushkin Fine Arts Museum, and those that will go to Kazan are now part of Moscow’s Lumiere Brother's gallery fund.

RBTH: What do World War II and Victory Day mean to you personally?

J. H.: Though my family wasn’t involved in the war, the father of my wife, who is French, fought in World War II, both in the French Army and the American army. He was in three different Nazi camps, from which he escaped. He found it very difficult that the decision was made in Western Europe not to celebrate the end of the war.

A lot of his friends died in the war and he felt that the lack of celebration was a mistake. But when my wife, who has been living in Moscow for 19 years, told him about celebrations here, he was quite moved by that.

For me it’s a very moving spectacle. I used to be a war photographer [ed. – Hill worked in Iraq, Afghanistan, Gaza, Georgia, Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh, Kosovo] and it's one thing to be an observer and another to be a participant. It’s very difficult to live with. I think it’s very important not to forget human life alongside the entirely political issues involved with the war.

On a personal level, these people went through tremendous experiences. It’s very painful to watch your friends die; it was painful to be asked to kill people. Later they had to live with big moral questions. And just to thank them for that is very important.

RBTH: What surprised you the most during your work with veterans? How did they react to a foreign photographer?

J. H.: It helped a lot that I speak Russian. Most of them were extraordinarily nice, dignified and warm. They were different people: some were sad, some were happy, they all were very emotional on this day. A few people refused to participate, but very few.

I’ve noticed a certain amount of tension between officers and solders. In Soviet historiography, the main role is for generals and officers. And I can’t say it’s not true, but in my experience of war, the people who are doing the fighting are the solders, not the officers. Once I was photographing a private and an officer asked me why I was photographing him, because he was only a private. But I think everyone played a role, so I was a bit surprised by this remark.

Overall, it was very moving experience, and humanizing. When I did the book, I went to see a writer, Boris Vasiliev. He wrote an introduction for it. When he looked at my images, he completely understood what I was trying to show. I was worried that people would be offended by some pictures, because I’m not showing them as heroes, but as humans. I told him I wanted a point of view from an ordinary participant, a solder like him. The idea was to see history from the bottom up.

RBTH: Did you manage to talk about the war with the veterans while working with them?

J. H.: I wish I had more time for that. What was often happening was that I stood without work for some time and then suddenly I had five people in a row. It was particularly interesting to talk to Navy officers who had contact with the Arctic convoys; they had been to Britain themselves.

RBTH: Why do you think World War II is so important for Russians?

J. H.: Obviously the scale. If you take the Vietnam War for instance, at the height of the war there were around 700,000-750,000 U. S. troops in Vietnam and about 55,000 died. That’s a lot of people, but if you compare these numbers to World War II, it's not so significant.

The Great Patriotic War touched everybody in the Soviet Union. You go to any village, any city in western Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and you see the list of the dead. Even 70 years later, it plays very deep role.

The fact of the invasion is also very powerful. Everyone in the post-Soviet space still feels the brutality of that. Britain was bombed, but not invaded, the U.S. had Pearl Harbor, but it wasn’t an invasion, it was something different.

In Pictures: The true face of bravery: War heroes captured on film

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox