Kissel, a berry juice. Source: Anna Kharzeeva

Every Russian child has a few strong dislikes — for some, it's the Russian language school teacher; for others, it's having to wear tights under pants in the winter. For me, it is kissel.

Kissel is like berry juice with starch in it. It was the gooey, disgusting, omnipresent nightmare of my childhood. It was impossible to avoid kissel. It was always served in the cafeteria in my kindergarten. I remember having lunch at my best friend's house and her mom putting a glass of kissel in front of me at the beginning of the meal. It would stare at me the entire time I was eating my soup and bread, trying to figure out how to disappear from their apartment on the 15th floor before it was time to have “dessert.” Finally an hour or so after lunch was over, my friend’s mom would realize I wasn’t going to even touch it and would kindly put it away.

One of the major perks of growing up was that kissel was officially out of my life. No more kindergarten cafeterias, no more awkward meals at a friend’s place. I was living the dream – until I realized that I couldn’t cook my way through the Soviet cook book without making it. Kissel was a crucial part of the Soviet diet.

Granny agreed: “Kissel was everywhere – in every cafeteria, and in the shops you could buy all sorts of varieties. They were ready made, too, sold in solid bricks – you just had to add water.”

My brother shares my hatred of kissel, unlike our mother and grandmother, who love it. My mom would apparently finish all the other kids’ kissel when she was in kindergarten – no one else liked it as much as she did. Why, why wasn't there someone like my mom in my kindergarten?

Approaching the recipe for kissel, I tried to be open minded. Maybe approaching it again as an adult, I wouldn't find it offensive at all. Maybe I could even tolerate it.

But, as it turns out, when it comes to disgusting things to eat, there is no room for open-mindness. Granny was sweet and ate all the kissel we made together.

I told her that I couldn't understand why anyone would spoil perfectly good juice by putting starch into it and turning it into an inconsumable nightmare.

Granny suggested this may have been a way to make it more filling – apparently if you have a glass of kissel, which of course I’ve never done, you’ll be quite full. She says it was the tea or coffee of the Soviet times – often served as “tretye,” or the third course. It was either that or a kind of juice made from stewed fruit called kompot.

A friend of Granny’s, who spent part of her childhood in an orphanage because her father was killed when she was 6 and her mother was arrested, says kissel was very beloved by all the kids, and indeed if any of the orphans did anything wrong, they wouldn't get a glass at lunchtime.

Granny says she doesn’t know anyone else who hates kissel as much as my brother and I do. I wonder if it's because we grew up with too much choice, or a genuine dislike we would have had even if we had grown up in an orphanage?

In any case, I am happy to go back to my kissel- free life!

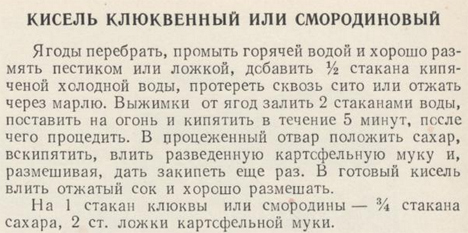

The recipe from the Soviet Cook Book, page 306

1 cup cranberries

¾ cup sugar

2 Tbsp. starch

Wash the berries with hot water then crush with a pestle or a spoon. Add ½ cup boiling water, rub through a sieve and squeeze through a cheesecloth. Set the juice aside.

Put the berry remnants in a pan and add 2 cups of water. Put on the stove and boil for 5 minutes. Then strain and keep the juice. Add sugar to the juice and boil again on the stove until the sugar dissolves.

Add starch and boil, stirring, until starch dissolves and mass has thickened. Add the reserved juice to the thickened mixture and stir well.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox