Empress Catherine the Great ordered for an enormous wooden rollercoaster to be built at her summer residence near St. Petersburg.

Lori / Legion-MediaIn the second half of the 18th century Empress Catherine II (the Great) ordered for an enormous 110-foot-high (33 meters) wooden rollercoaster to be built at her Oranienbaum summer residence near St. Petersburg.

Source: wikipedia.org

Source: wikipedia.org

Externally, the “mountains,” which were designed by court architect Antonio Rinaldi from Italy, already resembled the contemporary rollercoaster found in amusement parks. People would ride it in the summer using a special cart. Catherine II, however, even with all her love for fun, did not risk riding the rollercoaster, though she constantly invited all the foreign ambassadors and guests to try this extreme form of amusement.

French Baroness Anne De Stael (better known as Madame de Stael) wrote in her memoirs: "They've organized something similar to winter sleigh rides, the speed of which really entertains the Russians. They would ride a boat down the high wooden mountain with the speed of lightning."

In 1867 Tsar Alexander II brought a bicycle from Paris called “Bone Shaker.” It was freezing in St. Petersburg at the time and the emperor's sons, not waiting for the summer, organized races inside the Winter Palace.

"We would ride everywhere, even in front of the guards," remembered Grand Prince Sergei Alexandrovich. Back then bicycle wheels were made of solid rubber, which created a horrible rumble in the halls, while the outraged servants ran about to save all the precious objects.

For aristocrats it was bad manners to listen to folk music, and all the members of the imperial family preferred the latest compositions of Strauss, Tchaikovsky and Liszt. However, the imperial family could afford to take certain liberties. Thus, Tsar Alexander III enjoyed listening to gypsies at Gatchina Palace.

Actors in a tavern gypsy choir scene from the movie The Brothers Karamazov directed by Ivan Pyryev, Kirill Lavrov and Mikhail Ulyanov. Source: RIA Novosti

Actors in a tavern gypsy choir scene from the movie The Brothers Karamazov directed by Ivan Pyryev, Kirill Lavrov and Mikhail Ulyanov. Source: RIA Novosti

Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna, meanwhile, loved the balalaika. Her lady-in-waiting Sofia Buksgevden wrote in her memoirs how, "in Crimea after dinner they sometimes listened to a balalaika orchestra on their yacht called Standard," while the three-year-old tsarevich Alexei gave a solo performance in the orchestra.

The royal personalities had their own form of graffiti – they would scratch phrases and dates into panes of glass with their diamonds.

One such scrawl, left behind by Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna, has been preserved in St. Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum, in the Winter Palace: "Nicky 1902 looking at the hussars. 7 March."

It was written in English because for the empress, who was the granddaughter of Queen Victoria of the UK, English was her mother tongue.

The balls in the Winter Palace were often described as "wild" because the guests would not leave until sunrise.

Traffic would build up as the guests arrived, and the carriages back then were twice as big as cars today. Russia’s most famous poet Alexander Pushkin once complained to his wife that it took him three hours to approach the palace.

State Councilor Alexander Polovtsev wrote in his memoirs: "At 3 a.m., as the empress continues dancing, the emperor sends one of the dancers to order the musicians to stop. The musicians leave one by one and at the end just a violin and a drum are playing. It’s a repetition of Haydn's joke."

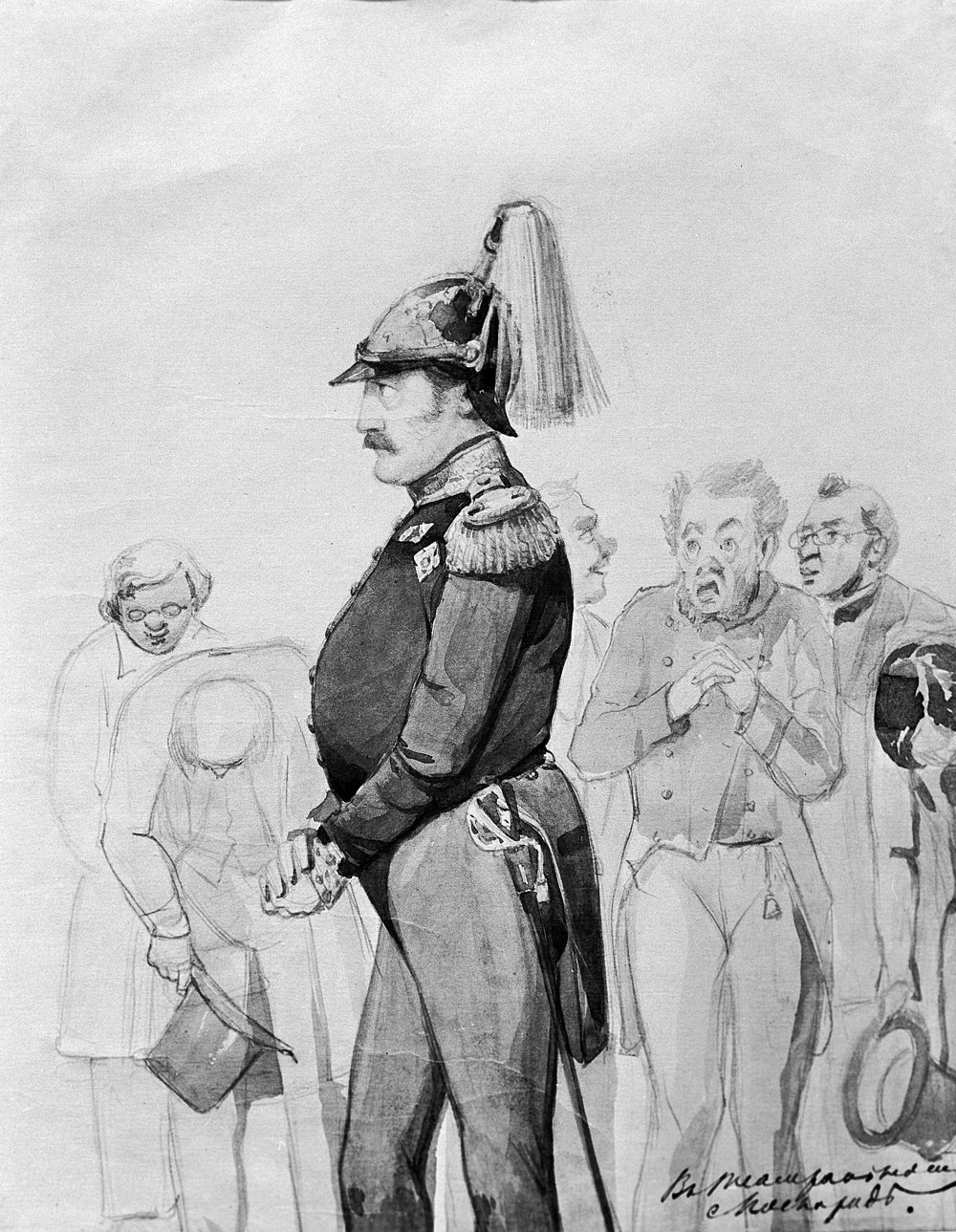

The passion for theatrical scaffolding often got out of hand. In his Notes actor Pyotr Karatygin remembers how Emperor Nicholas I once went on stage right in the middle of the vaudeville Box of the First Tier: "The emperor went behind the curtains, put on a gray overcoat and appeared on stage as a neighborhood policeman." A reproduction of "Nicolas I at a masked ball." The State Literature Museum. Source: RIA Novosti

A reproduction of "Nicolas I at a masked ball." The State Literature Museum. Source: RIA Novosti

In another French comedy the austere emperor played the role of a German who was knocked down by a Russian merchant.

Some of the royal figures in Russia practiced spiritualism. It all began when renowned Italian occultist Count Caliostro, who had organized spiritual sessions throughout Europe, came to Russia. Lady-in-waiting Anna Tyucheva wrote in her diary: "The tsarevich's entourage entertained itself by magnetizing tables and hats. A table would rise, spin around and pound the beat of the hymn ‘God Save the Tsar’."

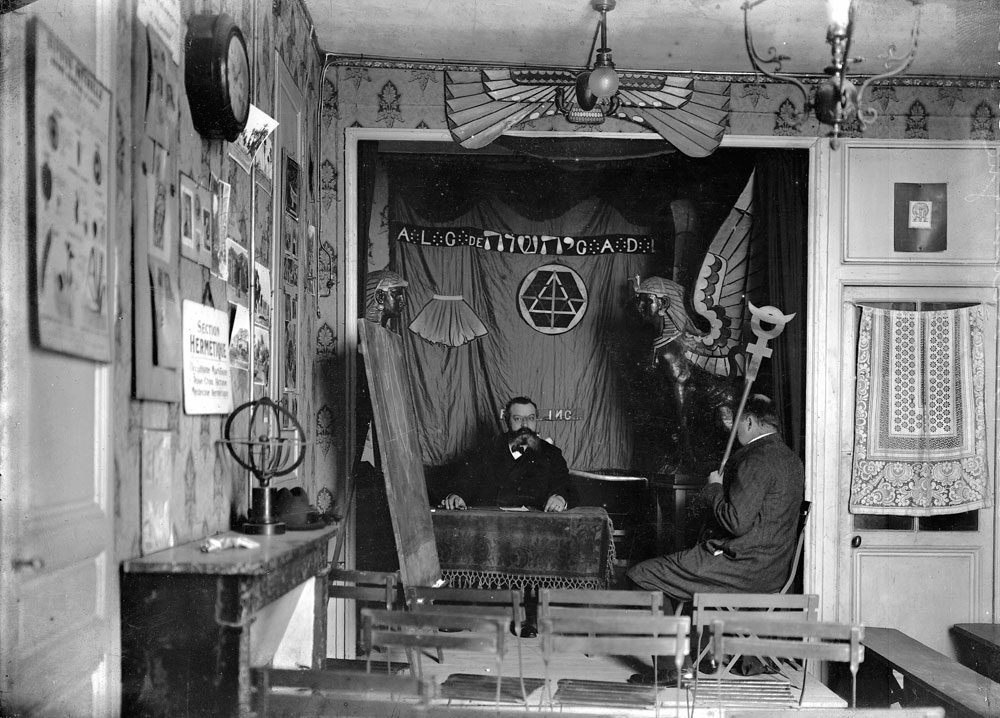

French occultist Papus. Source: Roger Violet / East-News

French occultist Papus. Source: Roger Violet / East-News

Also, in the book The Great Sorcerer historian Mikhail Pervukhin writes how French occultist Papus, upon Nicholas II's request, conjured up the spirit of Alexander III. The last Russian tsar wanted to ask his father for some political advice. According to Pervukhin, it was Papus who predicted the tsar's death.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox