Hermitage director Mikhail Piotrovsky: Palmyra must be restored

Columns are seen in the historical city of Palmyra, Syria, June 12, 2009. Satellite images have confirmed the destruction of the Temple of Bel, which was one of the best preserved Roman-era sites in the Syrian city of Palmyra.

ReutersWe are continuing to help Syria liberate Palmyra. Does it have a special meaning, now a cultural one?

Mikhail Piotrovsky: If we are able to liberate Palmyra, we'll have a really great story of the war for the liberation of Palmyra.

I do not think that the General Staff and the president planned the whole operation because of Palmyra, but the way it is – and there's a certain mystique about it – is that if our forces had been there, they would not have allowed fanatics to come close to Palmyra.

Mikhail Piotrovsky. Source: Denis Vyshinsky / TASS

Mikhail Piotrovsky. Source: Denis Vyshinsky / TASS

And of course, our forces have helped and are helping ensure that Palmyra – right now – may be liberated. If all this works, we will once again get an indication that the rights of culture are the most important. And that we all are ultimately fighting for culture.

If the result of our operation is the liberation of Palmyra, we will never find anything more beautiful in the annals of the whole of Russian history in the Middle East and the Holy Land. Pardon me for sounding solemn, but it's true.

Will it be possible to restore Palmyra after its destruction by fanatics?

M.P.: You know, I live in a city that has restored many of its palaces from scratch [after the Nazi siege during World War II – RBTH]. Of course, there is little left of Palmyra, but it is necessary and important to restore it.

This can be done, because some things have been restored and reconstructed there before. But now, first of all, we need to restore the knowledge about it. To create some new museums that tell the story of Palmyra. To restore it virtually, for a start.

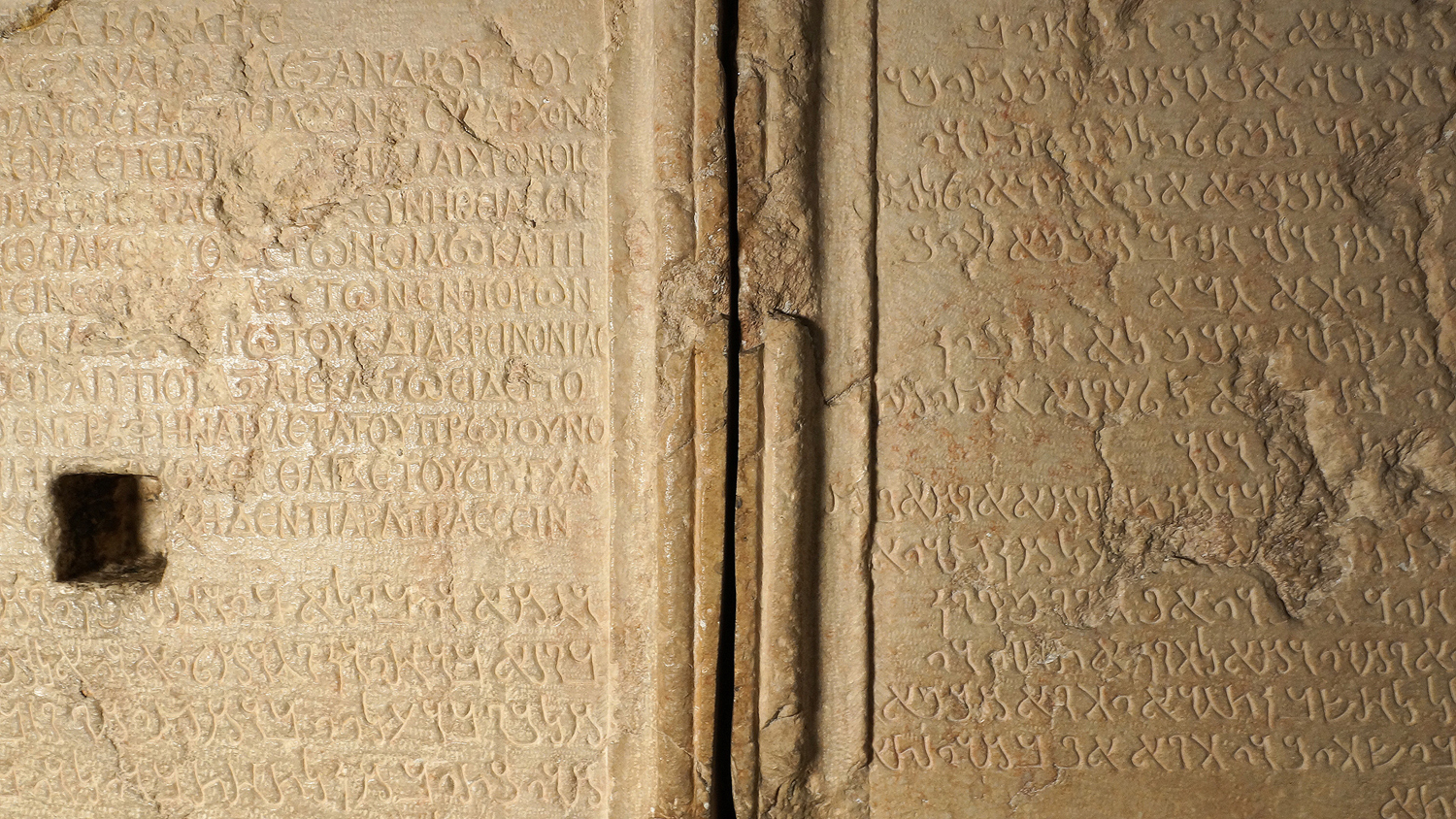

What are we doing? Our volunteers have invented a computer game called Palmyra Market. At the Hermitage, we have the Palmyra Tariff – a large stone slab inscribed in Greek and Aramaic.

It survived only because it was once transferred to our museum. Its story, too, can be turned into a game from the life of ancient Palmyra – on the topic of how much things cost and what caravans came to this city. We will definitely have holographic reconstructions of Palmyra monuments.

In May, we will open Intermuseum, and it will have a whole floor of the Hermitage section devoted to the General Staff and Palmyra. The thing is that the arch of the General Staff Building is exactly the same as the arch in Palmyra, joining together two different directions... St. Petersburg not only carries the name of the Northern Palmyra, but we have an architectural similarity to it, too.

And, of course, it must be restored, as we restored Pushkin and Tsarskoye Selo, having carried out most serious reconstruction and restoration there. It is necessary to raise the spirit of not only the Syrian people, but of all mankind.

The history of Palmyra now bears the terrible tragedy of its destruction. And this tragedy should be used for the benefit of mankind as we used the tragedy of the destruction of [the imperial St. Petersburg palaces of] Tsarskoye Selo, Pavlovsk, and Peterhof. People still cry in these palaces, looking at the pictures of the terrible destruction.

Palmyra monuments at the Hermitage

The Palmyra Tariff. Source: the Palmyra Tariff. Clich to view in the new window>>>

The Palmyra Tariff. Source: the Palmyra Tariff. Clich to view in the new window>>>

The Hermitage's Palmyra collection includes six burial reliefs, several sculptural fragments, a large slab inscribed in Greek and Aramaic – the Palmyra Tariff, as well as small items – coins and tesserae. The Palmyra Tariff – four blocks with inscriptions, weighing over 15 tons – is a diplomatic gift. The relief was found by an amateur archaeologist, Prince Semyon Abamelek-Lazarev, during his visit to Palmyra in 1882.

This is an abridged version of an article first published in Russian by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox