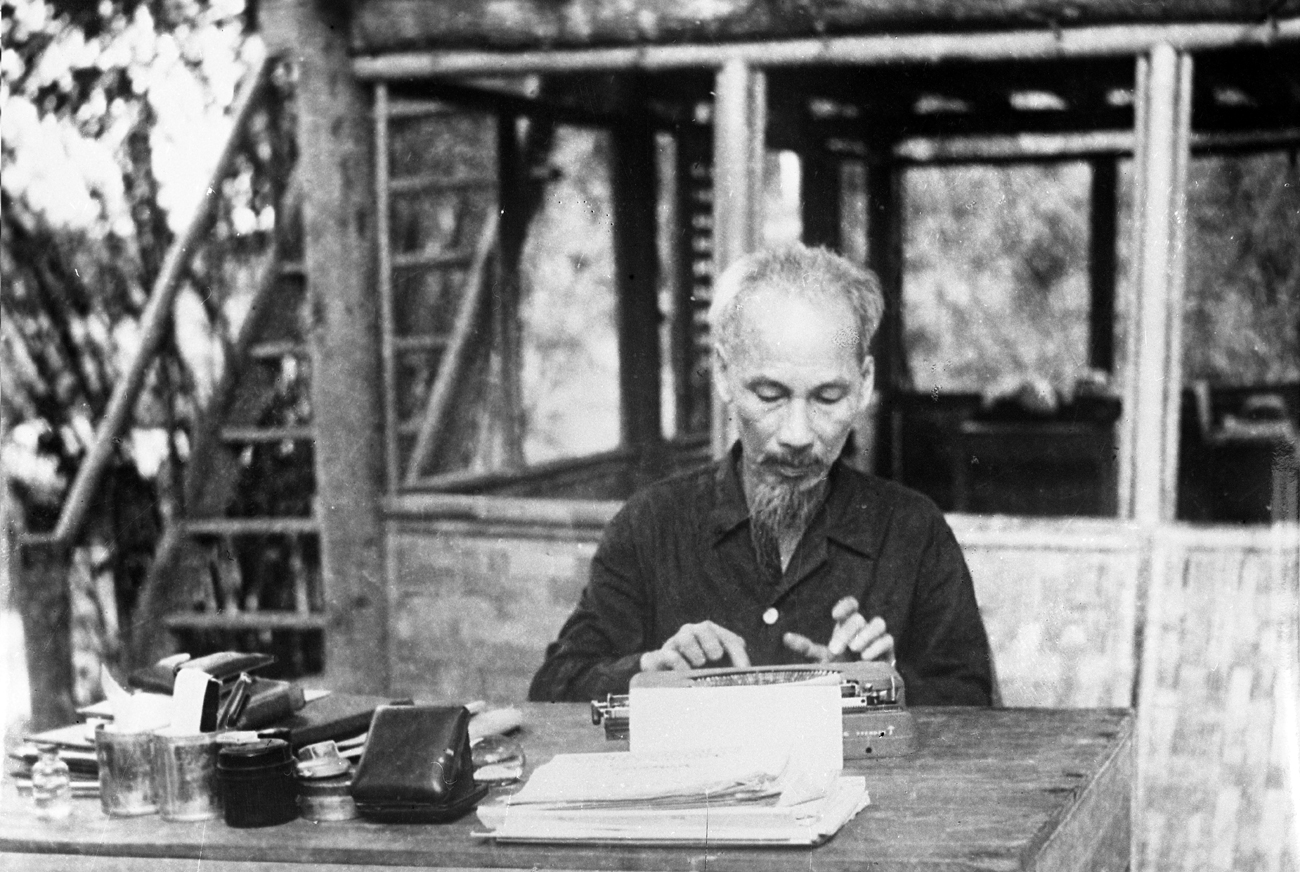

President of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam Ho Chi Minh at work.

RIA NovostiLong before Ho Chi Minh became the president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945, the Vietnamese revolutionary lived and traveled across Europe. In 1920, when he was 30 Ho became a founding member of the French Communist Party in Paris. He would move to Moscow within three years.

“More than hardcore communist leanings, it was Lenin’s call on the Western proletariat to support nationalist revolutions in colonized nations that inspired Ho Chi Minh,” says Nguyen Thanh Khu, a researcher from Hanoi, who studied in the USSR in the 1990s. “Also, his work in Paris in organizing the Vietnamese resistance to French colonization was noticed by the higher powers in Moscow.”

In his three years in Paris, Ho published two anti-colonial journals.

In Moscow Ho Chi Minh enrolled at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, an institution set up by Comintern, an international organization that aimed to spread communism around the world.

“The USSR wasn’t ready or strong enough at that point to directly back a freedom movement in Vietnam, but wanted to build up revolutionaries from all colonized nations,” says Khu.

After two years in Moscow, Ho moved to Canton (now Guangzhou) in southern China. His was officially employed by the Russian Telegraph Agency (now TASS) as an interpreter.

Over the next eight years Ho would often fall foul of the Chinese authorities for his role in mobilizing communist supporters. For years, he would evade the Chinese authorities and move across different parts of the country.

He was arrested by the British in 1931 in Hong Kong and then spent the next two years in prison. To resist extraditing Ho to the French colonial government in Vietnam, the British falsely claimed that he was dead, while quietly releasing him. The Vietnamese leader managed to hide in China before organizing enough funds to get to Vladivostok and travel across the country before arriving in Moscow in 1934.

“His arrival in mid-1934 did not merit a hero’s welcome; instead he was sent to study at the Lenin school for cadres,” wrote Sophie Quinn-Judge in ‘Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years. 1919-1941.” Ho was sidelined by the Communist Party and Comintern and not given any role in the party.

Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh, in the foreground, with other delegates of the 5th Communist International Congress, Moscow, 1924. Source: RIA Novosti

Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh, in the foreground, with other delegates of the 5th Communist International Congress, Moscow, 1924. Source: RIA Novosti

He studied at the Institute for National and Colonial Problems and also taught there until 1938.

“Given the fact that Ho wanted a mix of pan-Asian nationalism and communism, the latter years in Moscow were a great learning experience and something that set him up to lead the struggle against the French and Americans,” says Nguyen Thanh Khu. “His grand goal in Moscow was to help China become communist and friendly to Vietnam and then to help his country kick out the French.”

Khu says the Vietnamese leader remains a misunderstood figure, largely because of how the narrative on his life was hijacked after he died. There was a wrong belief that Ho was some sort of Russian agent, she adds.

“He was not a henchman of Stalin and may have never had a personal audience with him until 1950,” Quinn-Judge wrote.

Ho finally warmed up to both Stalin and Mao Zedong in the early 1950s. The USSR and China recognized the North Vietnamese regime as the legitimate government in Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh died before the end of the Vietnam War, and Russian specialists embalmed his body, which is on display in Hanoi.

It was Soviet and Chinese support that eventually helped North Vietnam defeat the United States and unite the country. The country has remained communist ever since, with Ho Chi Minh being regarded as a father figure.

With market reforms and openness to foreign direct investment, Vietnam has become one of the fastest growing economies in Asia. Now in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), red flags with the leader’s image blow in the wind towards the window displays of French luxury products.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox