Fabergé in London: How Russian Tsarist jewelry was adored in Britain

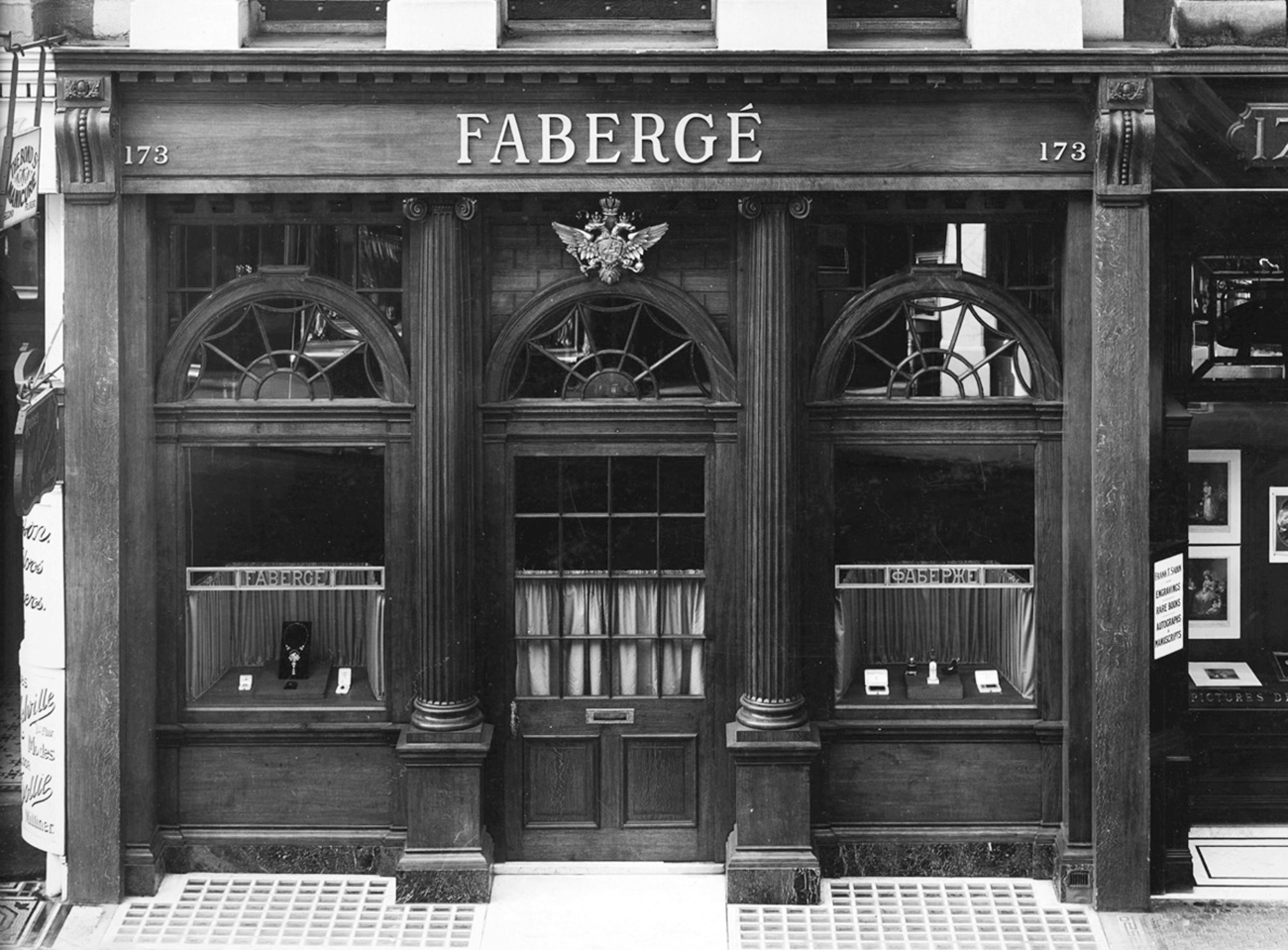

Faberge store on 173 New Bond street, London, 1910.

Archive PhotoWhile others focus on the Russian revolution in this centenary year, one London-based expert has turned his attention to the end of empire. Kieran McCarthy is a director of the historic London jewelers Wartski. He specializes in the work of Russian goldsmith Carl Fabergé, and has just written a book about “the incredible business that Fabergé established in London between 1903 and 1917”.

Lords and dukes

“Although Fabergé is viewed as a quintessentially Russian enterprise,” McCarthy told RBTH, “it was very much an Anglo-Russian affair. Russian art and culture entranced Britain in the Edwardian era and all of society flocked to Fabergé.” By the time Fabergé opened in London, there were already eighteen of the famous imperial Easter eggs. Seeking similar gifts, a glittering clientele of Maharajas, European royalty, newly rich business people, socialites, social climbers, American heiresses, South African lords, exiled Russian Grand Dukes and ballet dancers all buzzed around the famous jeweler’s shop like bees round a honey pot.

Henry Bainbridge, manager of Fabergé’s London branch, kept detailed information about his customers, who bought these treasures as presents. “As a consequence,” McCarthy explains, “it is possible to map out, through the exchange of Fabergé gifts, the ambitions, loves and even lusts of upper-class Edwardian Britain.” The writer Vita Sackville-West apparently equated gifts of Fabergé items with receiving lingerie in terms of intimacy, seeing them as a sign that a relationship was “in danger of becoming serious.”

International scope

Bainbridge called Fabergé the “greatest craftsman of the age”. Nephrite, rhodonite and obsidian from the Ural Mountains were fashioned in traditional ways; the materials and craftsmanship were indeed quintessentially Russian, but London was Fabergé’s “window on the wider world”.

Each purchase tells a story, like the declaration of eternal love conveyed by the elegant royal blue cigarette case, with its tail-eating diamond-encrusted snake, that Alice Keppel, his favorite mistress, gave to King Edward VII in 1908. Both the color of the royal blue enamel and the snaking symbol of everlasting love were significant.

In the same year, Stanislas Poklewski-Koziell, a councilor at the Russian embassy in London and friend of Edward VII, bought a pink and yellow enamel chrysanthemum, from Fabergé's London branch, the most expensive flower ever purchased there, and gave it to Queen Alexandra. Fabergé’s craftsmanship was the ultimate soft power, McCarthy jokes, “seducing the UK establishment”. His works became closely associated with the British Royal Family.McCarthy’s stylish volume of photos and historical research is the first book to be dedicated to the British Fabergé shop, the only branch outside Russia. Using previously unreferenced sources and a newly discovered archive McCarthy has studied the store's history, customers and exclusive stock. This was one of the “great unwritten books,” he told RBTH; “it alters our understanding of the patronage of art in this period.”

Jewelry and ballet

In 1911 the London Fabergé branch moved to a prestigious location on New Bond Street, just weeks after Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes opened its first season in London at Covent Garden. The ballets bewitched London audiences with the bright colors and bold Art Nouveau elements of their staging.

Ballet dancers like Anna Pavlova earned increasingly high salaries and were also able to spend it on jeweled gifts. The era saw a cross-fertilisation between jewelry making, performing arts and architecture. “Britain was intoxicated by Russia, from the country to crafts to dance to design,” says McCarthy, “and you see this unfettered love for Russia coming out through Fabergé.”

Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova (A screenshot from the movie "London Concert"). Source: RIA Novosti

Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova (A screenshot from the movie "London Concert"). Source: RIA Novosti

There has been a market in Britain for Russian elegance for centuries. Speaking in the little London antique shop Wartski, founded in 1865 by a Russian émigré and jeweler, McCarthy points out that the yellow-upholstered chairs we’re sitting on were sold off from the Winter Palace and the classical ormolu vase above the counter is from the Kremlin. The shop also has archives of photographs and letters and acts as a center for this kind of research.

McCarthy sits on the board of the Fabergé Museum situated in a restored palace in St. Petersburg. He is proud of the fact that, since the museum opened in 2014, it has shot from nowhere to number ten on TripAdvisor’s list of attractions in a city with a lot of competition. Even the pastel colors of the city – the yellow, pink and turquoise of the riverside mansions and palaces – are reflected, McCarthy points out, in the colors of Fabergé’s enamels.

Vanished era

In the early twentieth century, patrons with wealth and a desire for novelty collided with “a titan of the goldsmiths’ world”. It was in this meeting, McCarthy says, that Fabergé created his masterpieces. This “perceived Golden Age” in Britain lasted from 1901 to the outbreak of World War I. With figurines, silver horses and painted enamel views of landscapes, from Durham Cathedral to the dairy at Sandringham House, Fabergé immortalized Edwardian Britain. For aristocratic, émigré Russians, he also captured scenes in the “Old Russian” taste like the silver box, sold in London in 1912, with an enameled depiction of Nicholas Roerich’s 1902 painting of Rurik’s arrival in Rus on the lid.

Fabergé’s works “recall the romance of a carefree era long since vanished”, an era ruled by a “cultured elite”. Bittersweet nostalgia for this lost age is evoked in Philip Larkin’s elegiac poem “MCMXIV” (1914), which ends: “Never such innocence again.” Fabergé’s craftsmanship belonged, in Russia, to a late-imperial, pre-revolutionary era and in England, as in Russia, writes McCarthy: “Fabergé was the last flowering of Court art”.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox