Ataman Semyonov cossacks helped Mongolia achieve independence.

Archive PhotoThe landlocked country of Mongolia, which gave the world Genghis Khan and had the largest contiguous empire in history, was reduced to a subject of China’s Qing Dynasty by the 17th century. Being a nomadic Buddhist country, by the early 20th century, almost a third of the male population of Mongolia consisted of monks.

“While the vast majority were disconnected from Peking, the winds of change blew on the country at the same time as the collapse of the Qing Dynasty,” Lubsan Kiribizhekov, a China and Mongolia scholar from Russia’s internal republic of Buryatia, told RBTH.

“Russia’s Romanovs, who had an antagonistic relationship with the Qing Dynasty, and had a long border with Mongolia, stirred the pot and encouraged revolutionaries.”

Kiribizhekov, who is based in Hong Kong, added that Mongolia was involved in a power play between Russia and China in the early 20th century. “Tsar Nicholas II wanted Mongolia to initially be an independent state under Russian influence.”

In 1911, when plans were unveiled by the Qing Dynasty to resettle ethnic Han Chinese in Mongolia, there was a great degree of resistance from the people in the territory. “The very idea of resettling Chinese in Mongolia was supposedly to stop a Russian takeover of the region,” Kiribizhekov added.

Bogd Khan, a religious leader with Tibetan roots, who led the Mongolian independence movement, sent a delegation to St. Petersburg requesting both military and diplomatic assistance for his cause. While Russia refused to provide military assistance, it agreed to use diplomatic channels to help the movement.

Winter Palace of Bogd Khaan, Ulan Bator, Mongolia./Source: Flickr/yeowatzup

Winter Palace of Bogd Khaan, Ulan Bator, Mongolia./Source: Flickr/yeowatzup

“Sando, the Chinese Viceroy in Mongolia, was asked by the Qing Dynasty to negotiate with Bogd Khan and make him withdraw the request for Russian assistance but he lacked the diplomatic skills and behaved in an arrogant manner,” Kiribizhekov said. “The Khan took advantage of the volatile situation in Peking, where the Qing Dynasty was on the verge of collapse, and organized a bloodless revolution and declared independence from China.”

A Mongolian delegation, backed by armed Russian Cossacks under the command of Grigory Semyonov, demanded that Sando leave Mongolia and that Peking recognise the independence of the country. Sando had to agree and was escorted to the Russian consulate for protection and safe passage back to China. Peking however refused to recognize Mongolian independence, although it virtually had no control over the country.

Although it did not officially recognize Mongolian independence, Russia welcomed a buffer state that could halt Japanese expansion in Northern Asia. Just six years earlier, Russia had suffered a humiliating defeat to Japan in a war that cost Moscow half of Sakhalin Island.

Emboldened by the independence of what is called “Outer Mongolia” by the Chinese, Bogd Khan looked to establish a greater Mongolia that would include Inner Mongolia (which was in China) and other lands traditionally inhabited by Mongolian people.

“This is when Nicholas II sensed the real danger,” Kiribizhekov said. “The Tsar feared a large Mongolian state that would comprise of modern day Mongolia and Inner Mongolia, and claim parts of Russia. In such a case, Russia would have had a serious rival instead of a buffer state with China and Japan.”

Bogd Khan ruled Mongolia from 1911 to 1919 and again from 1921 to 1924. The country made numerous attempts to annex Inner Mongolia.

Emperor Nicholas II and Crown Prince Alexis, in the background, carried by a Cossack attendant, 1913. / RIA Novosti

Emperor Nicholas II and Crown Prince Alexis, in the background, carried by a Cossack attendant, 1913. / RIA Novosti

While Russia maintained that Mongolia was an autonomous region of China, it agreed to train the Mongolian Army in return for commercial privileges.

“In this geopolitical game, parts of the modern-day internal Russian republic of Tuva became a Russian protectorate, and a 1915 tripartite agreement between Russia, China and Mongolia, recognized the country as an autonomous part of China,” Kiribizhekov said.

With Russia engrossed in the First World War, China managed to sway Bogd Khan to fully recognize Peking’s sovereignty over the country. “For a few years, Russia was not a player in Mongolia, and China managed to have control over large parts of the country,” Kiribizhekov said.

The ensuing Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian Civil War meant that Moscow’s attention was diverted away from Mongolia.

Ataman Grigory Semyonov / Library of Congress

Ataman Grigory Semyonov / Library of Congress

During the Civil War, Cossack leader Grigory Semyonov mobilized Cossack troops, Buryats and ethnic Mongols to help form a greater Mongolia, but did not enjoy Bogd Khan’s support. Friction between Buryats and Inner Mongolians led to the failure of Semyonov’s plans and China managed to completely seize control of Mongolia.

“Semyonov was a visionary, who could have changed the course of Mongolian history, but his plans could never materialize,” Kiribizhekov said. By 1919, Mongolian autonomy was abolished.

Once China reoccupied Mongolia, it again commenced its program to resettle Han Chinese in the country. The resistance movement was strong in the country, and about to get assistance once again from the White Russians, who were loyal to the late-Tsar Nicholas II.

In October 1920, White Russian troops invaded Mongolia and managed to get the backing of Bogd Khan. In early February 1921, a force comprising of Mongolian volunteers, Buryat and Russian Cossacks defeated the Chinese and forced them out of Urga, now Ulaan Bataar. Some Chinese troops managed to reach the northern borders of Mongolia, while most fled south to Inner Mongolia.

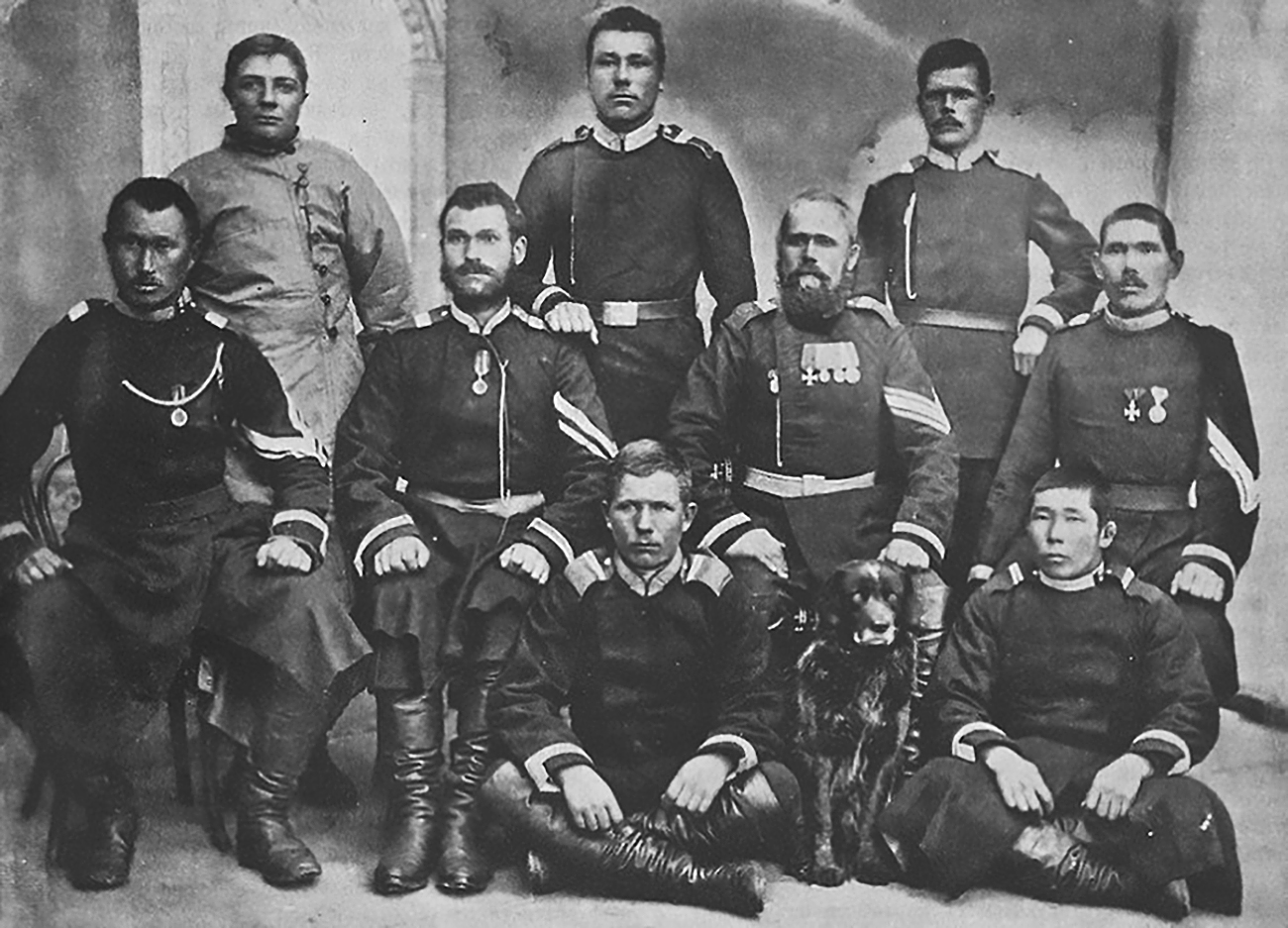

Group of cossacks / Archive Photo

Group of cossacks / Archive Photo

A month later, the Soviet Red Army and troops loyal to Mongolian revolutionary Sukhbataar attacked Mongolia, defeating both White Russians and the Chinese troops.

“This invasion was known as the ‘Mongolian Revolution of 1921’ and essentially created the modern Mongolia,” Kiribizhekov said. “There have been stories of Sukhbataar and Vladimir Lenin meeting in Moscow, but these are probably untrue. Mongolian communists even presented a statue of the two leaders in conversation to the Soviet Union.”

Mongolia adopted the Cyrillic script and remained a Soviet satellite state till 1990 when another revolution established democracy.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox