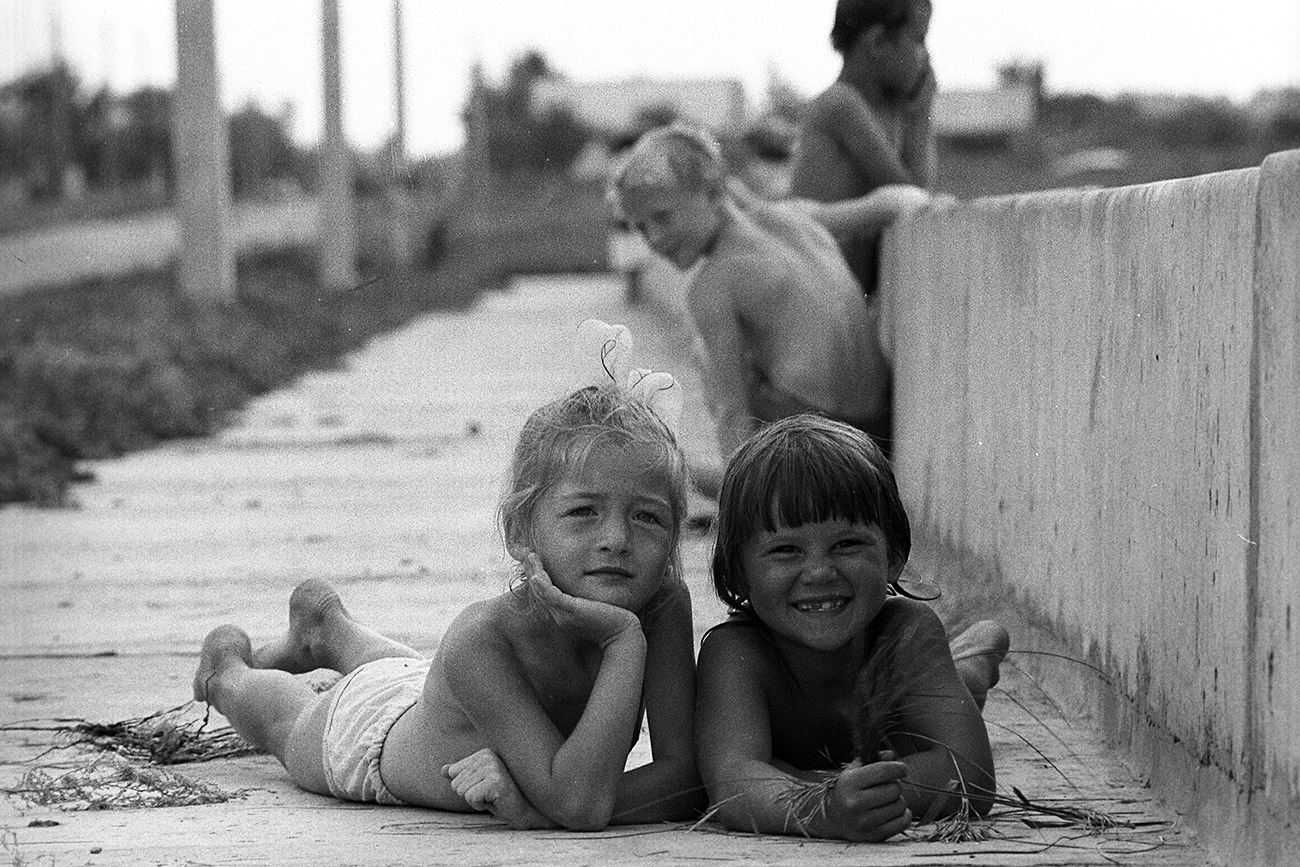

Young Muscovites.

Igor Zotin/TASSIf a child has Internet access you can safely bet they will spend their summer holidays online. But how did children in the Soviet Union entertain themselves, before the Internet had been invented? Well, thinking outside the box was key!

Pioneers of Young Sailor pioneer camp on a camping trip / Tihanov/RIA Novosti

Pioneers of Young Sailor pioneer camp on a camping trip / Tihanov/RIA Novosti

Soviet children would spend massive amounts of their holidays outdoors, only coming home when they absolutely had to. A summer hike with classmates – lasting days or even weeks – was always hotly anticipated, and kids would learn valuable survival skills like making campfires and map reading. It was always an adventure, nothing short of the tales written by Jules Vernes and James Fenimore Cooper, who Soviet kids loved so much.

Young Pioneers (Soviet schoolchildren aged nine to 14, equivalent to today’s Scout movement) would be supervised on a hike by a Pioneer leader, who explained everything from the history of the region they were hiking in, to how to find minerals. In the evenings the group would gather around the fire, cook and devour a simple dinner (mostly tinned meat and potatoes baked in the campfire’s ashes) and sing to a guitar.

A collector of car models. 1968 / Boris Ushmaykin/RIA Novosti

A collector of car models. 1968 / Boris Ushmaykin/RIA Novosti

Children of all ages usually collected something such as model trains, cards with cartoon characters, or decal (a design prepared on special paper for durable transfer onto another surface such as glass or porcelain). Every self-respecting decal collector had some on display, either stuck onto their bedroom window or some other glass surface, usually against their parents’ wishes. These pictures would never come off no matter how hard mum or dad scrubbed. Other collectables included postal stamps and rare coins, all of which could be swapped with friends.

Student of the music and arts boarding school gets ready to enter Bogorodsky Wood Carving College, 1990 / TASS

Student of the music and arts boarding school gets ready to enter Bogorodsky Wood Carving College, 1990 / TASS

For every child old enough to be trusted with a penknife, whittling figurines out of wood was an enjoyable pastime. Toy boats, swords, and slingshots would also be created, so finding a suitable branch always took time – old table or chair legs would also do. Bottles or cans lined up on a wall became target practice, with stones catapulted from slingshots. Parents would look on with concern etched onto their faces, afraid a stray stone might smash a window or worse, hit their child in the eye.

Girls during French skipping after school classes. / ussr-kruto.ru

Girls during French skipping after school classes. / ussr-kruto.ru

While the boys were busy cutting wood and smashing bottles, the girls entertained themselves with French skipping, a wildly popular pastime during the Soviet era. The game involved three girls and a long piece of elastic tied into a circle. Two of the players (the “holders”) would stand inside the elastic facing each other, place it around their ankles and tighten it into two parallel strings of rubber. The third one (the “jumper”) would perform a series of increasingly difficult moves over the strings. The ring would be gradually raised to the holders' knees, thighs, waist – and if the jumper was skilled enough – ears!

If the jumper made a mistake she had to rotate positions with one of the holders. There could be more than one person jumping at a time if the elastic was long enough!

Children in a village of Saratov Region. / Vitaliy Karpov/RIA Novosti

Children in a village of Saratov Region. / Vitaliy Karpov/RIA Novosti

Getting your hands on chewing gum in the USSR was difficult. Only rarely would some lucky kids' parents bring some from abroad. Such delicacies would be chewed into oblivion, long past each stick had lost its flavor.

Children dipped them into jam or sugar to add some taste past a certain point. It may sound strange, but for those unfortunate souls with no hope of finding gum, road tar was plucked from the streets and chewed instead. It could also be pulled off roofs where it was used as sealant. Tar is hard at first, but chew on it long enough and it softens - we don’t advise you give this a go today.

The schoolchildren watch funny slidefilms during a big break, 1984. / Sergey Edisherashvili/TASS

The schoolchildren watch funny slidefilms during a big break, 1984. / Sergey Edisherashvili/TASS

Strict parents would send their kids to bed immediately after the legendary Spokoynoy nochi, malyshi! (Good night, little ones!) children's television program. The older ones were allowed to stay on for a little longer, reading a book or looking at filmstrips in the dark.

Filmstrips were pieces of color photographic film, with each frame representing a different episode in a story, with pictures and text. The film roll was fed into a special projector, a distant relative of the first movie projector. Watching filmstrips was a family event. A white bed sheet would be hung on a wall or a wardrobe to serve as the screen. The projector would be put up on a stack of books, the film fed into it, and the lights switched off. Mother, father, or the elder sister or brother read the text aloud, and the younger kids listened and gazed at the illustrations.

An ordinary interior of an apartment in USSR, 1979 / Nikolai Akimov/TASS

An ordinary interior of an apartment in USSR, 1979 / Nikolai Akimov/TASS

Those who did not have a filmstrip projector at home would have to settle for staring at a carpet on the wall. Such carpets, usually hanging above the sofa or bed, could be found in virtually every Soviet apartment. They served a dual purpose: Concealing imperfections in the wallpaper and as sound insulation. Trying to fall asleep at night, children would turn to face the carpet and seek out silhouettes of animals, contours of human faces, or outlines of plants its patterns. Each child would see different things and try to point them out to their brothers and sisters.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox