How Russian literature's 'enfante terrible' Limonov lived in the U.S. and France

Eduard Limonov (Savenko) turns 75. No matter what his age is, he remains reckless and radical in both art and life

Sergei Karpov/TASS“I consider myself to be scum, the dregs of society… I am scum,” that’s how Eduard Limonov, a famous and scandalous Russian writer who has published more than 50 books, began his first novel, It’s Me, Eddie, which was written in New York City in 1976.

The book tells the story of a vagabond Russian immigrant, Edichka (Eddie, short for Eduard), barely surviving in the U.S. in complete despair. Though Limonov always emphasizes that he and his lyrical hero are not the same, he admits that it’s his story to a great extent.

In the 1970s Limonov began his journey to the

From tailor to émigré

The cover of Limonov's first novel dedicated to his life in New York City

By 1974, after he had left the USSR, Limonov had already lived quite a life. A provincial poet from Kharkiv (now Ukraine) Eduard Savenko took the punk-sounding nom-de-guerre, Limonov, (associated both with lemons and

At first, he had to work as a tailor to make ends meet, but then his poetry grew popular in bohemian circles, among artists and authors not fond of the authorities. In 1973, he married Elena Shchapova, a model

It’s unclear why precisely Limonov left Moscow. In 1992, the author would claim that the KGB (Soviet secret service) tried to convince him to become their snitch, with departure as the only alternative. Nevertheless, in another

In the lower depth

Moving to the U.S. didn’t make Limonov happier – his wife Elena dumped him almost immediately after they settled down in New York City. Broke, lonely and completely unknown in a strange land (he barely knew English), the author hit the very bottom of society, living on welfare and aimlessly wandering through his American life.

It’s Me, Eddie, Limonov’s first novel, was born out of these harsh circumstances – the author describes a hopeless man, both pitiful and arrogant, verging on the brink of collapse. A furious howl full of cursing and pornographic scenes, It’s Me Eddie is characterized as Limonov’s “confession.” The protagonist, Edichka, weeps for Elena and tries to get over her through meaningless sex with both women and men, abusive drinking and embittered denial.

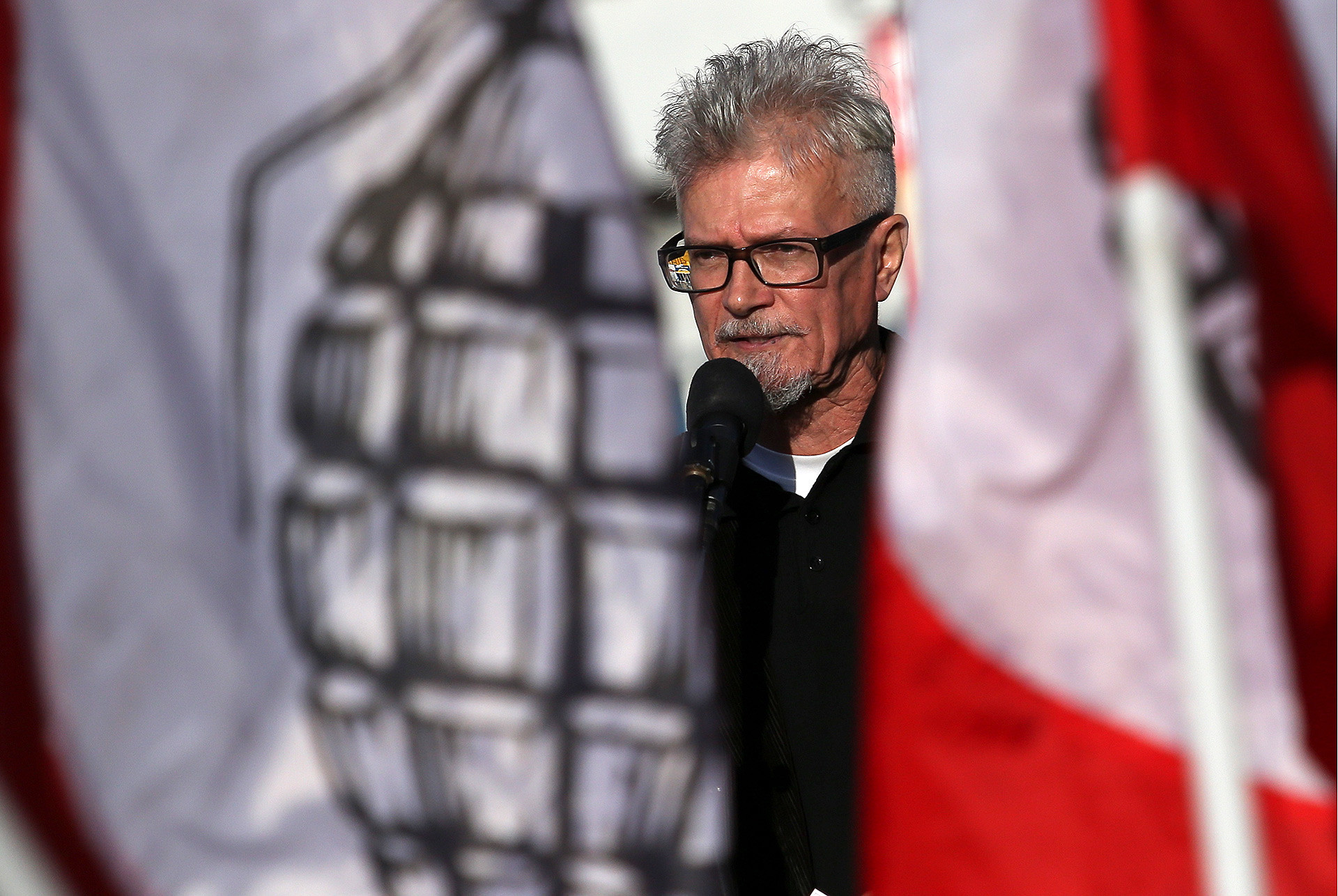

Nihilist, anarchist, punk

The author always was a radical - abroad and after his return to the Motherland. (Photo taken in 1994, on a political rally.)

Tatiana Kuzmina/TASSUnlike many émigrés, Limonov ignored the American “bourgeois” way of life. In It’s Me, Eddie he wrote: “I receive welfare. I live off your labor: you pay taxes and I don't do s***... What, you don't want to pay? Well, then why the f*** did you get me to come here? Take it up with your propaganda – it's too strong.”

This declaration was true only to some extent Limonov had jobs, including as a busboy, a proofreader at a Russian newspaper, and a housekeeper at a millionaire’s mansion. But he loved befriending outcasts: the Trotskyist Workers’ party, vagrants and punk rockers. In one of his short stories, The First Punk, he recalls reading Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem, Left March, on stage at a punk concert.

Crossing the Atlantic

Limonov portrayed in 1987, his 'French era', when he was living in Paris with his second wife.

Nevertheless, Limonov dreamt of success and desperately tried to publish his novel. About 35 American publishers refused to have anything to do with It’s Me, Eddie, considering it outrageous and anti-cultural.

So, in 1979, he found one in France – Jean-Jacques Pauvert, who had previously published the writings of the Marquis de Sade. “I owe him a lot. He discovered me,” Limonov would say later. In France, the novel had another title: “Le poète

After that, success found Limonov, and he became famous and was able to live on his literary income. He continued to write his “fictional memoirs” – stories of life in America, France and of his young years as a Kharkiv thug. In 1980, Limonov moved to Paris with his fiancé, Natalya Medvedeva, a poet and a singer.

A Russian Frenchman

On this picture (taken in 2015) Limonov is far older than during his years in France, but his redoubtable style remains the same.

Besides politics, the writer enjoyed life in

As soon as the USSR collapsed, however, Limonov closed the chapter of his life in

Check out our list of the best books by Ludmila Ulitskaya

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox