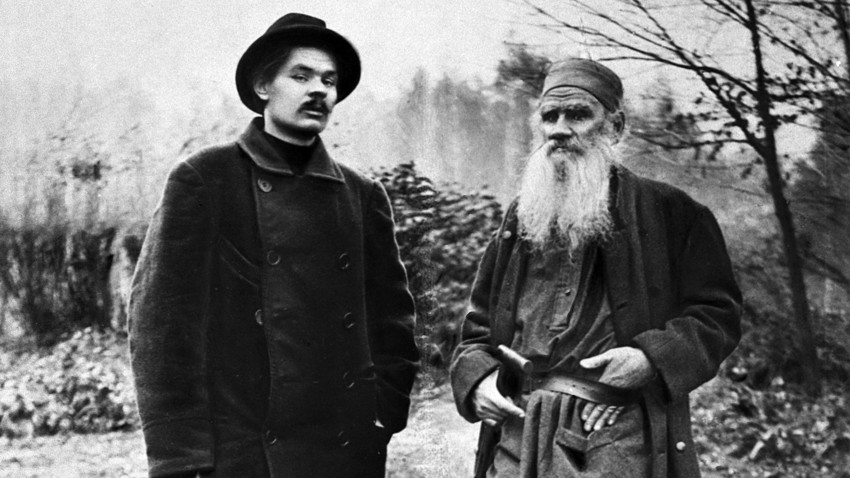

Maxim Gorky and Leo Tolstoy in Tolstoy's estate Yasnaya Polyana, 1900. Reproduction

SputnikThis year, Russia celebrates the 150th birthday of one of its most important

***

Tolstoy’s first diary entries about Gorky were favorable. “We had a good conversation,” “a true man of the people,” or “I am glad that I like both Gorky and Chekhov, particularly the first one.” But from about the middle of

“Gorky – there is a misapprehension,” Tolstoy writes on Sept. 3, 1903, adding angrily: “The Germans know Gorky, but they don't know Polenz.”

But Wilhelm von Polenz (1861-1903), a prominent German writer of the naturalist school, could not compete with Gorky, who by 1903 had become famous in Germany with his play, The Lower Depths, which premiered at Max Reinhardt’s Kleines Theater in Berlin on Jan.10, 1903 under the title, Nachtasyl (Night shelter). It was staged by the well-known director, Richard

It is silly and ridiculous to suspect Leo Tolstoy of envy, but there was a certain element of

Actor Ivan Moskvin (R) as Luka and Margarita Savitskaya as Anna in Maxim Gorky's play 'The Lower Depths' staged by Konstantin Stanislavsky and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko at the Moscow Art Theater

SputnikThe suspicion of jealousy increases if we read his diary entry for April 25, 1906. At the time, Gorky, together with actress Maria Andreeva, were on their scandalous tour of America, meeting writers and giving interviews, and all this was widely reported not just in the American press but also the Russian press. “I read in the paper about Gorky's reception in America,” writes Tolstoy, “and found myself feeling annoyed.”

Here are the diary entries for Dec. 24 and Dec. 25, 1909. “I read some Gorky. Neither fish nor flesh.” So what was he reading? The play, The Philistines. But why did he read it so late, given that it is Gorky's first play, dating to before The Lower Depths? “Last night,” he writes on Dec. 25, “I read The Philistines by Gorky. Miserable.”

On Nov. 9 and Nov. 10 of the same year: “At home in the evening, I finished reading Gorky. All imaginary, unnatural, enormous heroic feelings and hypocrisy.” Again – “hypocrisy”! Admittedly, he adds: “But the talent is big.”

The talent is big but the work is miserable and hypocritical?

Nevertheless, the great old man's interest in the “hypocritical” writer does not decrease. A diary entry for Nov. 23 of the same year, 1909, goes as follows: “I read about Gorky after dinner. And, strange to say, I had a negative feeling towards him, with which I am struggling. I explain to myself that, like Nietzsche, he is a harmful writer: A major gift and an absence of any religious convictions at all – i.e. any concern with the significance of life – and together with that a cocksureness, supported by our ‘educated world’ which sees him as its spokesman, a cocksureness which is infecting that world even further. Take his saying: You believe in God – and there is a God; you don’t believe in God – and there is no God. A vile saying, but all the same it made me think hard. Does the God in Himself about whom I speak and write exist? It’s true that one can say of that God: If you believe in Him, He exists. And I always thought so. And for that reason in those words of Christ, ‘love God and your neighbor,’ a love of God has always seemed to me superfluous, and incompatible with love of one’s neighbor – incompatible because love of one’s neighbor is so clear, clearer than anything can be, while love of God, on the contrary, is very unclear. You can accept that He exists, this God in Himself, that's true, but can you love Him?... This is where I encounter something I have often experienced – a slavish acceptance of the words of the Gospel.

“God is love – that is so. We know Him only because we love Him, but that God in Himself exists is a rationalization, and often a superfluous and even harmful one. If I am asked: Does God in Himself exist? I am bound to say and will say: Yes, probably, but I don't understand anything about Him, this God in Himself. But it isn't so with the God of love. Him I know for certain. He is everything to me, the explanation and the purpose of my life.”

In

The great Leo continued to be annoyed. Here is an entry dated Jan. 12, 1910, the last year of his life. “After dinner I went to see Sasha [his daughter – Pavel Basinsky], she is ill. If Sasha hadn’t been reading I would have written her something agreeable. I took something of Gorky's from her. I read it. Very bad. But the main thing that it's not good that I find this false assessment objectionable. I should see only good in him.”

Behind all of Tolstoy’s angry and irritable comments about Gorky it is impossible not to glimpse an intense, partisan and even jealous attitude towards him. Tolstoy realized that Gorky voiced the sentiments of the new generation of young people and this was the reason for the exorbitant attention that the intelligentsia paid to Gorky. Tolstoy did not consider Gorky to be a “voice of the people.”

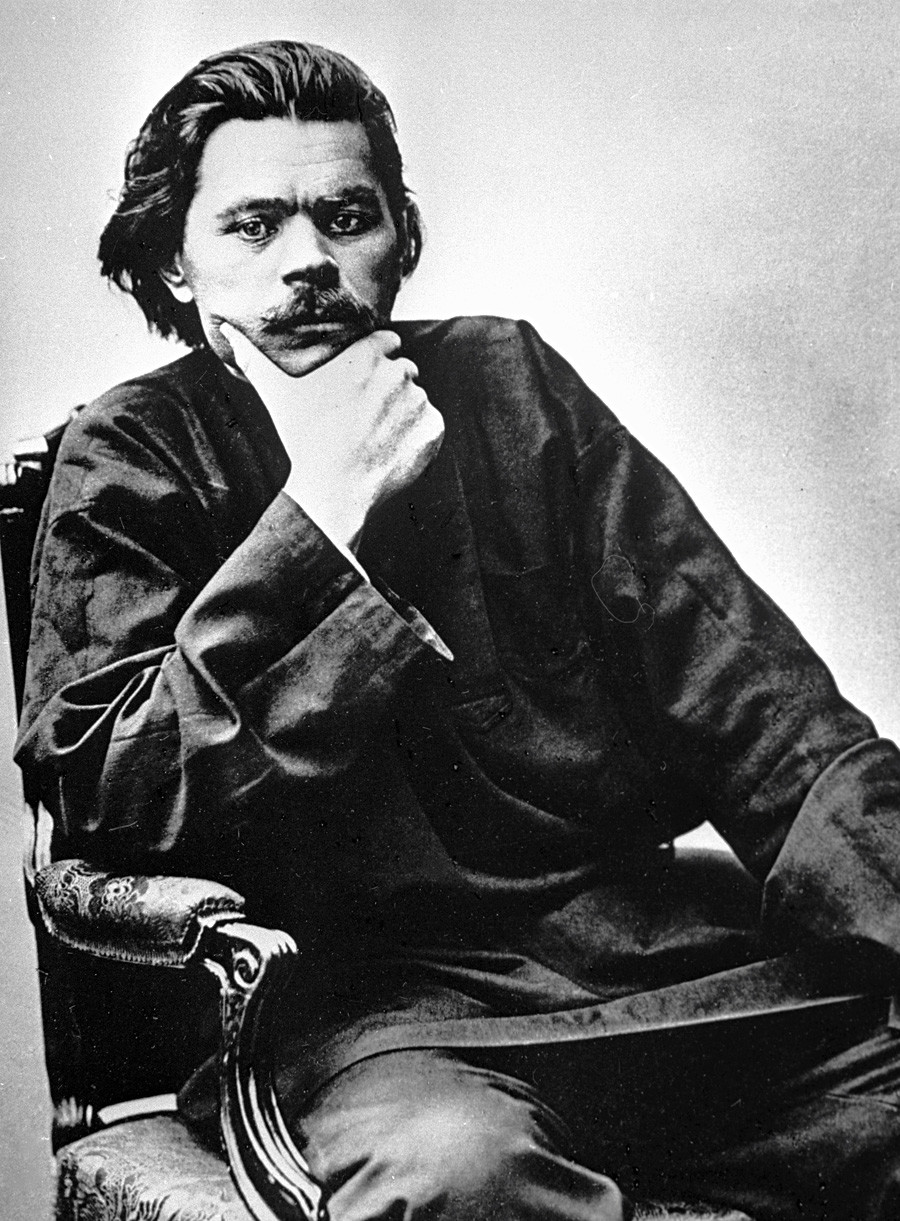

Maxim Gorky

SputnikBut Gorky was in the vanguard of the new era with its new ethics and new culture. Gorky was throwing down the gauntlet. Tolstoy did not know how to respond to the challenge. Thus, Gorky was for a short time the man who put Tolstoy “to the test.” Particularly in the person of Luka, the wily old man who unsettled Tolstoy’s faith with his words about God.

Whereas Gorky was merely one episode in Tolstoy’s life, Tolstoy exerted one of the strongest possible influences on Gorky. In Tolstoy, Gorky had encountered someone who put him “to the test,” but in a way that was not even remotely comparable to the way the cook Smury or Romas had done [characters in the autobiographical works, In the World, and My Universities – Russia Beyond]. The only person in Gorky’s spiritual biography who came close to Tolstoy was his grandmother, Akulina Ivanovna. Gorky felt Tolstoy’s death as acutely as he had the death of his grandmother:

“Leo Tolstoy is dead.

There was a telegram and in it the announcement was made in the most commonplace terms: he had died. It was a blow straight to the heart. I howled from anguish and grief and now, in some kind of dull-witted state, I can see him before me as I knew him and saw him. I desperately want to talk about him.”

When his grandmother had died, Alyosha Peshkov [Gorky's real name – Russia Beyond] did not cry. But it was “as if an icy wind had swept over” him. And once again, as in the case of his grandmother’s death, he had no one to talk to, apart from his dearest departed.

***

Read more: 3 must-read books by an iconic Soviet writer Maxim Gorky

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox