William Brumfield in the field near village of Predtecha, Totma Region (Vologda Province), August 2011

Personal ArchiveIt’s 1970. A young man from the American South arrives in Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport. It’s his first trip to the Soviet Union, but he’s not worried. He’s traveling with a group of fellow Slavic specialists from the U.S., and he carries a small Konika camera and just two rolls of Kodachrome film (36 shots each) that he bought especially for this trip.

This young man’s name was William Brumfield, then a Ph.D. student at the University of California at Berkeley. In 1970, he knew little about photography or Russian architecture, and didn’t plan to spend hours on busy trains and sleeping on the porches of Russian churches in his effort to capture the best photo.

Now, he is probably the best-known expert on Russian architecture, the only American fellow of both the Russian Academy of Architecture and Construction Sciences, and the Russian Academy of the Arts, as well as author of more than 100,000 photos of important architectural sites across Russia. Why did he decide to devote his life to documenting Russia’s architectural heritage?

“During my first trip, in the summer of 1970, Russia literally opened my eyes to my own gift. There, I started doing photography,” Brumfield, now 73, told Russia Beyond. “When I came back to the U.S. and developed those two rolls of film I was astonished by the high quality of the pictures. I quickly decided to return for an entire year, as a dissertation scholar at Leningrad University.”

That trip proved even more productive, with over a thousand images. During the next several years as an assistant professor at Harvard, Brumfield experimented with photography and found a publisher in Boston who wanted to do a book.

Yet, it was easier said than done. American academia didn’t support Brumfield’s new interest in Russian architecture. “Are you a Slavist or not?” he recalls them questioning his new passion.

Young Brumfield near Andronikov Monastery in Moscow, 1979

Personal Archive“Slavic programs at the top universities were not interested in a thorough specialist in Russian architecture, nor were art historians. These prestigious universities have vastly greater resources than the one that ultimately gave me refuge (Tulane University); yet, their lack of vision – in every sense of the word – was ubiquitous. Those resources were closed to me. The answer: a partisan struggle that made the most of whatever resources and allies I could find in the U.S. and in Russia,” he told Russia Beyond.

With the help of friends, the young Brumfield managed to get a position in the Moscow-based Pushkin Institute, and as director of an American student group he once again could visit Russia and fulfill his photographic aspirations.

“I practically didn’t see my students, I was crazy roaming around Moscow and other cities capturing pictures,” he remembers. Yet, there was one important restriction on his travel. Like American diplomats, he wasn’t allowed to go far from the Soviet capital and was closely watched by the KGB.

“Once in 1979, I was desperate to go to the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin on the Nerl River,” Brumfield recalls. “I had been there once but wanted to go again to take pictures from another angle, so I secretly joined the excursion of another group from the Pushkin Institute but was quickly uncovered. I got to Vladimir and then went to the church by myself. When I arrived the weather was really bad plus some reconstruction was underway, so my expectations were disappointed. At the same time I felt that someone was watching me. There were indeed two men standing nearby taking photos of me. We exchanged words: I said ‘what a beautiful monument,’ and one replied ‘Yes,’ and then added, ‘the people’s path to it will not be overgrown,’ quoting Pushkin. It was a strange meeting, but nothing bad came of it. The KGB knew that I was unlikely to pose any threat.”

Belozersk, December 2010

Personal ArchiveWith time Brumfield managed to avoid restrictions by traveling secretly with his Russian friends, namely Dr. Alexei Komech, who became director of the Moscow Art Research Institute and a fierce supporter of Russian architectural preservation. Together, he showed Brumfield new sites by suburban train and bus.

In 1983, the first of Brumfield’s many books appeared – Gold in Azure: One Thousand Years of Russian Architecture, which featured photos only from sites that he was allowed to visit. With time and more books to come, he traveled wherever he wanted, documenting more and more important sites.

“I placed all my bets on this work, and it was my stubbornness that helped me pursue my passion,” said Brumfield, now Professor of Slavic Studies at Tulane University. Articles, books, lectures and electronic photo archives – he uses every channel possible (including our website) to transmit his unique knowledge, experience and photos to a global audience.

A major influence on Brumfield’s decision to explore Russia was his father’s memories meeting with Russians. “My father, who was born in 1895 near a hamlet north of Lake Pontchartrain on the Mississippi-Louisiana border, was the first person I knew who had seen Russians, and in a very improbable way,” said Brumfield. “In 1918, he served in the Sixth Marine Regiment as part of the American Expeditionary Force in France. Toward the end of that year he encountered Russians who had been part of a little known but sizable Russian contingent in the French Army on the Western Front. He never forgot the experience. He told me that the Russians were our allies, that we should never fight them.”

Brumfield's father in Aix-les-Bains, France, 1918

Personal ArchiveBrumfield also can’t recall any negative moments or conflict situations with Russians. The latter have always treated him with love and respect for his work. “A bridge between Russia and the West”, “a unique person who traveled all over Russia, for whom our country has become his second home” – these are just two of the remarks made by Russians attending one of Brumfield’s public talks in Russia.

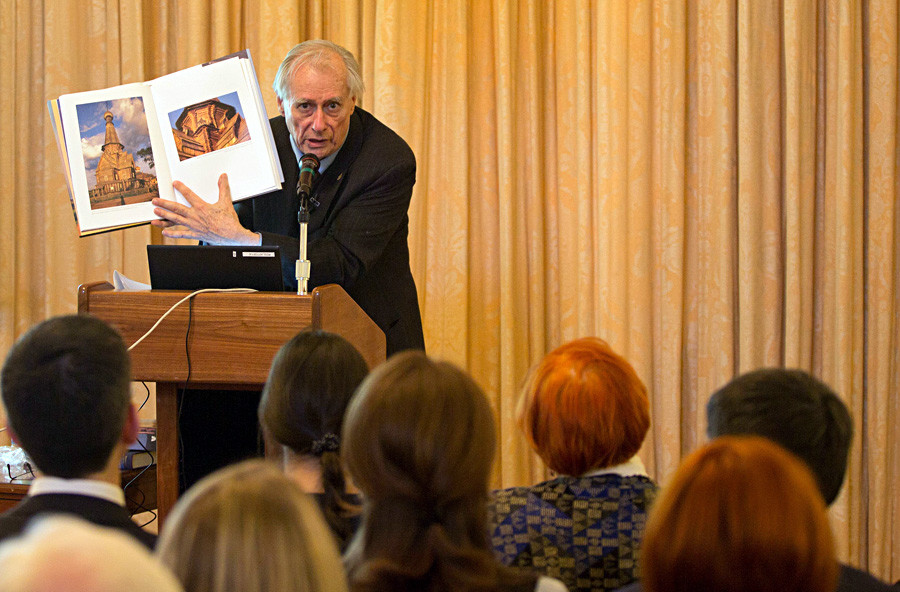

William Brumfield gives a lecture at the U.S. ambassador’s residence in Moscow, Spaso House, March 2017

U.S. Embassy in Russia“Americans often think in stereotypes. While some colleagues understand the work that I do, the majority of our Slavists rarely visit Russia. This worries me. Everyone who values Russian culture should see it, but our academics tend to think in narrow categories and that they know everything – when in fact they don’t. I do my best to wage a partisan struggle against this blindness,” he says. “I devoted my life to studying Russian culture in images, not just words. I made my choice and paid the price, but I don’t regret it.”

This story is a part of Russia Beyond’s new series of articles to inform about the bigger picture of bilateral relations between Russia and Western countries. We are focusing on individual contributions and the role of people who are “creating bridges” between our countries, despite the political intrigues and “muscle flexing.” Know anyone like this? Please contact us here: info@rbth.com.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox