The artist, activist, curator and urban art researcher, Igor Ponosov, has examined the power of street art in Russia by exploring its historical background, from the avant-garde movements of the early 20th

***

In the early 20th century, combatting academic stagnation, bourgeois art, and ‘museumification,’ Russian avant-gardists were among the first to proclaim the necessity of art to engage with the city. Art manifestos and decrees reflected their views on the ‘promulgation’ of bourgeois art through the movement of its objects into urban public space and their subsequent contextualization.

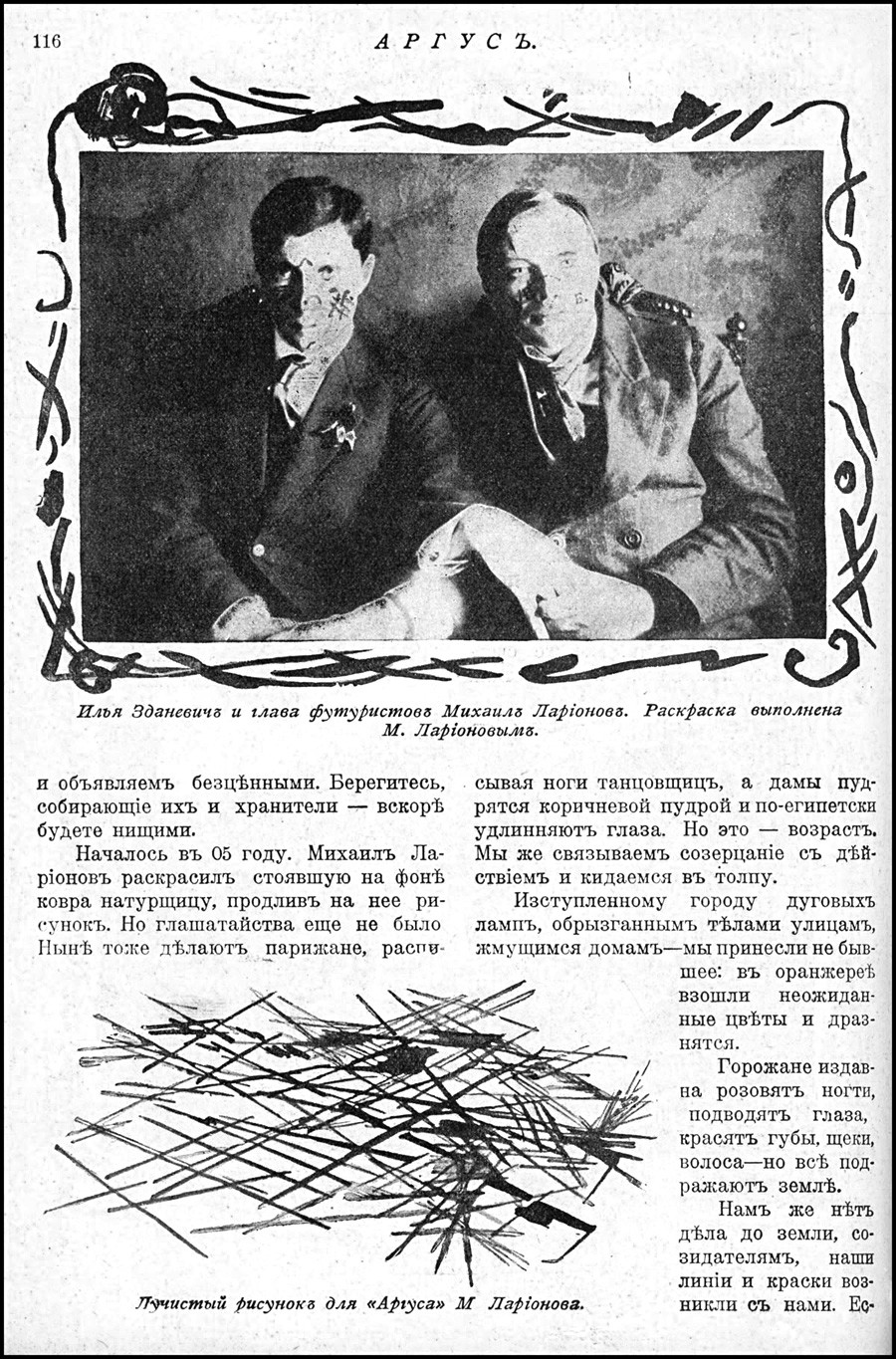

A manifesto 'Why We Paint Ourselves'

Archive photoThe first call for artists to come out into the streets was in public announcements made in 1912 by Ilya Zdanevich (Iliazd), proclaiming the worthlessness of contemporary art, and persuading artists to draw closer to the people and to engage in making outdoor posters and signs. Cautious attempts to insert art into everyday life were undertaken by the Futurists, by means of épatage, i.e. in a manner which violated accepted social or cultural norms.

In 1913, Ilya Zdanevich and Mikhail Larionov (1881–1964) produced a manifesto entitled, Why We Paint Ourselves, in which they announced their intention to paint their faces with bright colors. The artists named this action “the beginning of an invasion.”

L-R: Andrei Shemshurin, David Burliuk, Vladimir Mayakovsky

Anna Akhmatova State museum in Fountain HouseIn 1914, Kazimir Malevich, together with Alexei Morgunov (1884–1935) and Ivan Kliun (1873–1943), organized a performance, a so-called ‘Futurist demonstration,’ in which the artists strolled down Kuznetsky Bridge with red wooden spoons in the buttonholes of their jackets, indicating their proximity to the people. In the artists’ view, these spoons were a symbol of the rapprochement between the artist and the people, rejecting elitism. In pre-revolutionary

From 1916–1918, on the eve of the October Revolution, there were discussions within the Futurist environment on the subject of ‘Fence painting and literature,’ and on the rethinking of art as such. Mikhail Matyushin (1861–1934), David Burliuk (1882–1967), Kazimir Malevich, Alexei Kruchenykh (1886–1968), Ilya Zdanevich, Vasily Kamensky (1884–1961), and others, were actively involved in these debates. ‘Fence painting and literature’ is a controversial lecture by Kazimir Malevich alongside other futurists.

The scandalous aspect of the event was the emphasis of the lecturers on the fence in literature and obscene painting, which at that time was associated with something sordid, for example, with insults and abuse. The futurists tried to create a path from elitism to the people, breaking the established rules of fine art. Campaigns encouraging people to take to the streets can also be traced through several poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893–1930), who was also active in these discussions

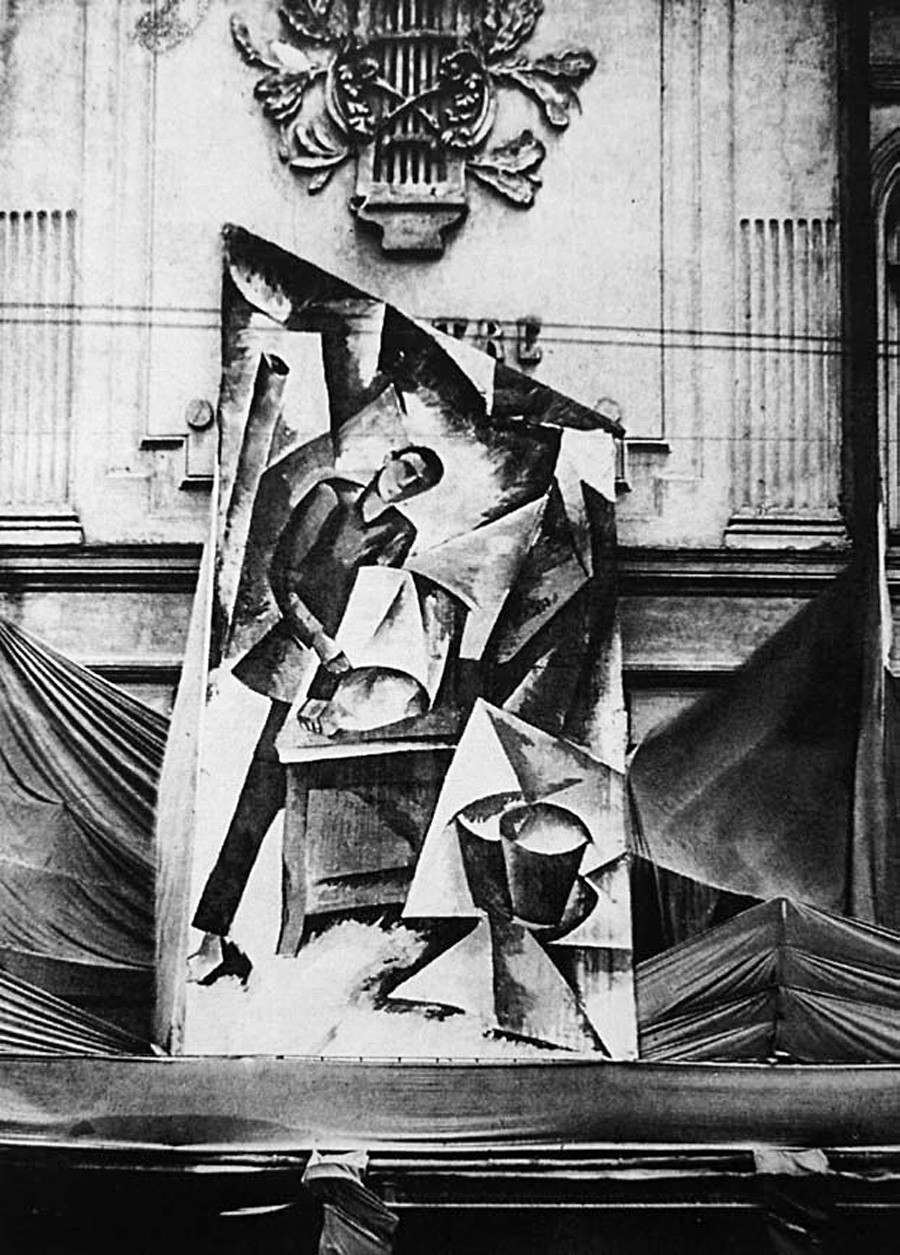

Alexander Osmerkin. Design for Moscow's Zimin Opera dedicated to the first anniversary of the October Revolution, 1918

Irina Bibikova, N. Levchenko/ Iskusstvo magazine,1984The decree contains clear evidence of the call to create an artistic revolution in the art of the early 20th century: “From now on, may a citizen walking down the street enjoy every minute of the intensity of thoughts of great contemporaries, contemplate the flowery brightness of exquisite joy today, listen to the music – melodies, rumble and noise – of excellent composers everywhere.”

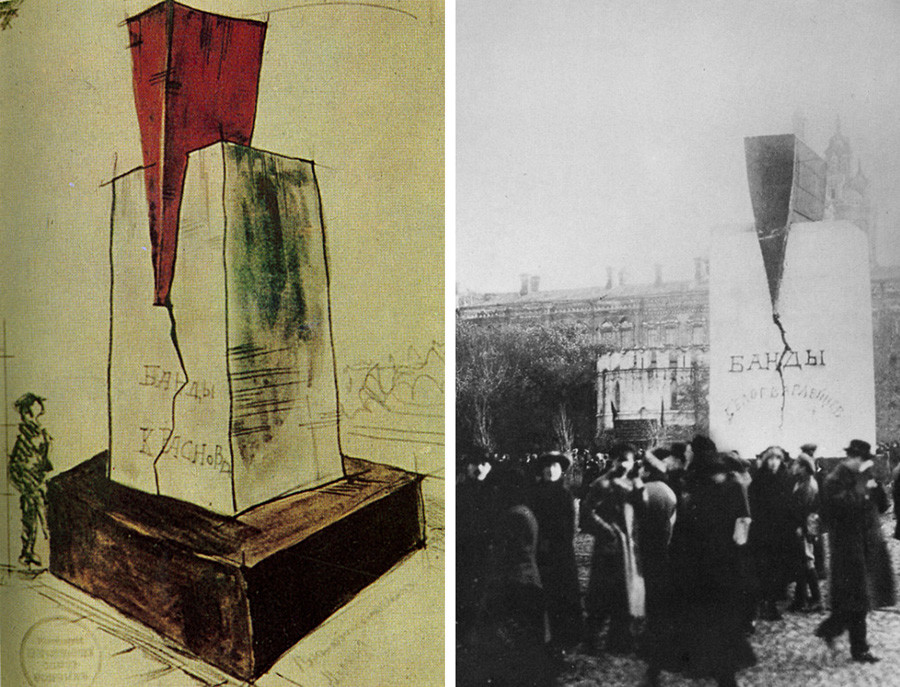

On the left: Nikolai Kolli. A sketch for the 'Red Wedge' architectural composition. On the right: "The Red Wedge" on Revolutsii square in Moscow, 1918.

Irina Bibikova, N. Levchenko / Iskusstvo magazine, 1984“Let the streets be a place for everyone to celebrate art” — all of this is very much in tune with the events of October 1917, and the era of the reforms in Tsarist Russia. On this fertile ground of rejecting the existing system, we can say without a doubt that the Russian Futurists set the tone for contemporary art in a new socialist Russia, based primarily on legal equality and the elimination of elitism

Decorations for Soviet celebrations

Irina Bibikova, N. Levchenko / Iskusstvo magazine, 1984

Decorations for Soviet celebrations

Irina Bibikova, N. Levchenko / Iskusstvo magazine, 1984

Decorations for Soviet celebrations

Irina Bibikova, N. Levchenko / Iskusstvo magazine, 1984Initially, the revolutionary celebrations were reminiscent of military marches, with mock battles, displays of trophies and the people’s enemies, as represented by the bourgeoisie, religion, and 'traitors' of the revolution. In the first years of such celebrations, and up until the mid-1920s, demonstrations were based more on amateur and folk performances, than on engaging professional artists.

Decorating White barracks in Vitebsk by Malevich and students of the Art School, 1919

Getty ImagesIn 1918, this balance reflected the fact that May 1st was not just the date of the universal contemporary art showcase, or as the publicists of that time wrote, “The First Folk Exhibition,” but it was marked significantly by the involvement of the people in the production of art itself.

Read more: 7 very unusual 20th century avant-garde buildings in Moscow

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox