“The Beatles brought us the idea of democracy,” rocker Sasha Lipnitsky was once quoted in Leslie Woodhead’s book How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin. “For many of us, it was the first hole in the Iron Curtain.”

In fact, contraband Beatles records were the vinyls to get your hands on in the Soviet Union in the sixties and seventies. The Iron Curtain’s impermeable partition was no match for the band’s dedicated Eastern bloc following, who smuggled their records in bulk and then became hippies, dissidents, and era-defining musicians.

In hindsight, a love of these heartthrobs from Liverpool was one of the few things that bridged the divide between Westerners and Soviet citizens. This was a time when McCarthyism addressed communism’s “threat” from the right and the New Left was busy digesting Orwell and Solzhenitsyn and deciding that the Soviet Union was no longer cool. The Cold War, the thinking went, was no laughing matter.

The Beatles may have embodied popular culture at the time, but that couldn’t stop them being complete smart asses. Ever the antagonists, they couldn’t help but to try and tear this new Western narrative to pieces. Enter the White Album’s opener, “Back in the U.S.S.R.”

From start to finish, everything about “Back in the U.S.S.R.” is tongue in cheek. Before we even get into the song’s Cold War politics, there’s the sound – the upbeat, seven-bar blues-drenched piano riff is a complete and obvious spoof of The Beach Boys’ signature sound (though thankfully, Mike Love was on The Beatles’ retreat in Rishikesh, India while the song was being written, and gave it his seal of approval). Then there’s the title, which managed to poke fun at both Chuck Berry’s flag-waving “Back in the U.S.A.” and British Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s “I’m Backing Britain” campaign at the same time.

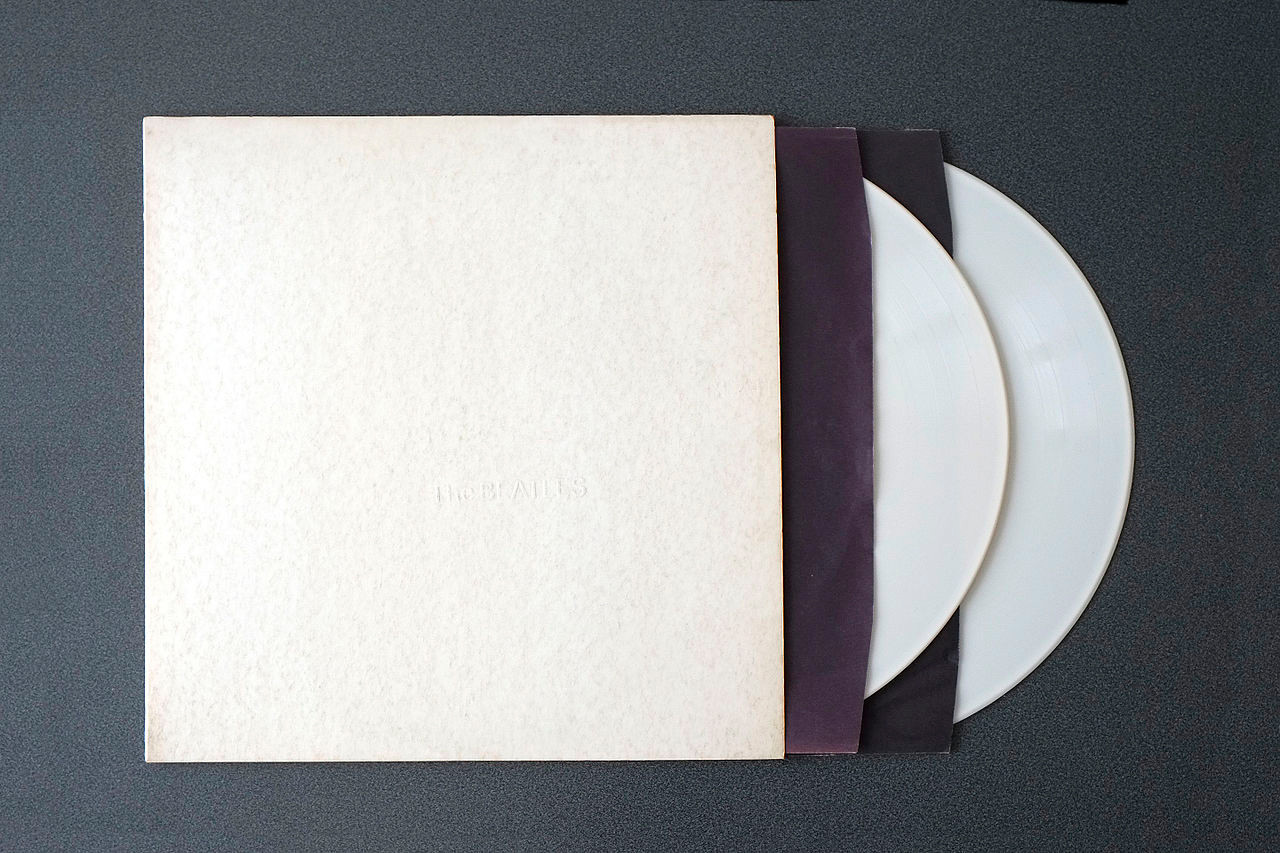

1968's 'The Beatles', aka the White Album

Patrick Despoix/WikipediaOf course, the trolling seen in the iconic song is impressive not only for its multifacetedness, but for its ability to provoke such an uproar from so little. Lines like “The Ukraine girls really knock me out” and “Let me hear your balalaikas ringing out,” far from being celebrations of Soviet culture, were rather little more than light mockeries of its perceived unsexiness (let’s just say the women of Moscow and Ukraine didn’t have the reputation in the 1960s that they have today).

Then there’s “Georgia’s always on my my my my my my my my my mind,” a nod to Hoagy Carmichael’s 1930 hit “Georgia on My Mind” – the only difference, of course, being its referral to the North Caucasus country rather than the southern U.S. state.

In a sense, what made “Back in the U.S.S.R.” satire at all had less to do with what it said about the Soviet Union, and more to do with the fact that it mentioned the communist country at all. For what was essentially a jokey, role-reversed take on The Beach Boys’ “California Girls,” the only resemblance of a political message we can possibly draw from the song is its portrayal of Russians and Americans at parity. As Paul McCartney explained in his biography, the song’s protagonist is “someone who hasn’t got a lot, but they’ll still be as proud as an American would be.”

Among the paranoia of 1968, however, this was enough for a scandal.

To be fair to the people of 1968, they did get the joke. The now 19-times platinum White Album was The Beatles at their most human and playful; in the LP’s wider context, “Back in the U.S.S.R.” was just a rawer, more hard-hitting form of the audacity laced throughout the record.

Others, however, weren’t so impressed. Anyone to whom a parody of classic rock’s slightly propagandistic tinges could be interpreted as Soviet propaganda itself, now deemed The Beatles worthy of sanctimonious political anger in the U.S. The ultra-conservative John Birch Society, for one, took particular offence to the line, “You don’t know how lucky you are, boys” and charged the band with fomenting communism and sympathizing with the enemy.

Beyond outrage came conspiracy theories. Right wing commentator Gary Allen (the Alex Jones of his day) drew parallels between “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and other White Album classic “Revolution” to conclude that The Beatles were in fact Stalinists who “took the Moscow line against Trotskyites.” Allen is also credited with starting the widespread rumor that the band made a secret journey to the USSR and gave a private concert to the Central Committee, a theory somewhat mitigated by the Soviet government’s labelling of The Beatles as “the belch of Western culture.”

Unsurprisingly, parts of the New Left also levelled more minor criticism at the song for its timing amidst the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Ian MacDonald summed this sentiment up in his 1995 book Revolution in the Head by remembering the song as a “tactless jest.”

In a 1964 interview, John Lennon responded to criticisms of The Beatles being “un-American” as such: “Well, it was very observant of them because we aren’t American, actually.”

True to form, the quartet was completely unfazed by the criticism around “Back in the U.S.S.R.” In a defiant reach out to The Beatles’ Soviet fanbase, McCartney told Playboy, “It was hands across the water… ‘cause they like us out there, even though the bosses in the Kremlin may not.”

President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin meeting with ex-Beatle Paul McCartney in the Kremlin, Moscow. May 26, 2003.

Sergey Guneev/SputnikNaturally, no song better demonstrated the band’s verboten connection with its Soviet fans than “Back in the U.S.S.R.”, performed illicitly (but by popular demand) by Elton John at the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. When Paul McCartney finally recited the peacemaking anthem in Russia in 2003 with Putin in the front row, the crowd went into meltdown.

It wasn’t a surprise, either; “Back in the U.S.S.R.” is timeless, but for reasons beyond The Beatles’ global appeal. In a tense world of spying allegations, proxy wars, and shoe-banging, the song was just about political enough to irk the world’s overlords, while playing as a private joke to everyone else. Musical satire just doesn’t get more poignant than that.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox