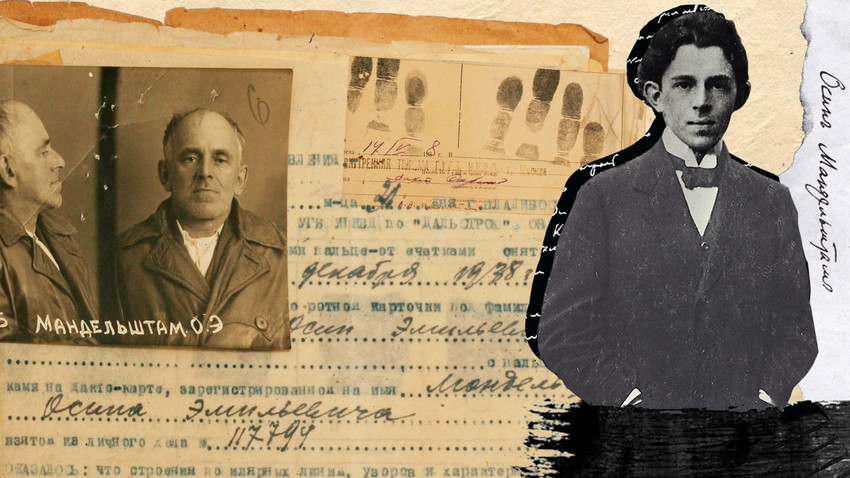

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) was one of the greatest poets of the Silver Age of Russian poetry. He died under mysterious circumstances in a Gulag camp in the Far East. We look back at his life to recall why his legacy is so important.

1. He was the last Russian intellectual

Vadim Nekrasov/Global Look Press

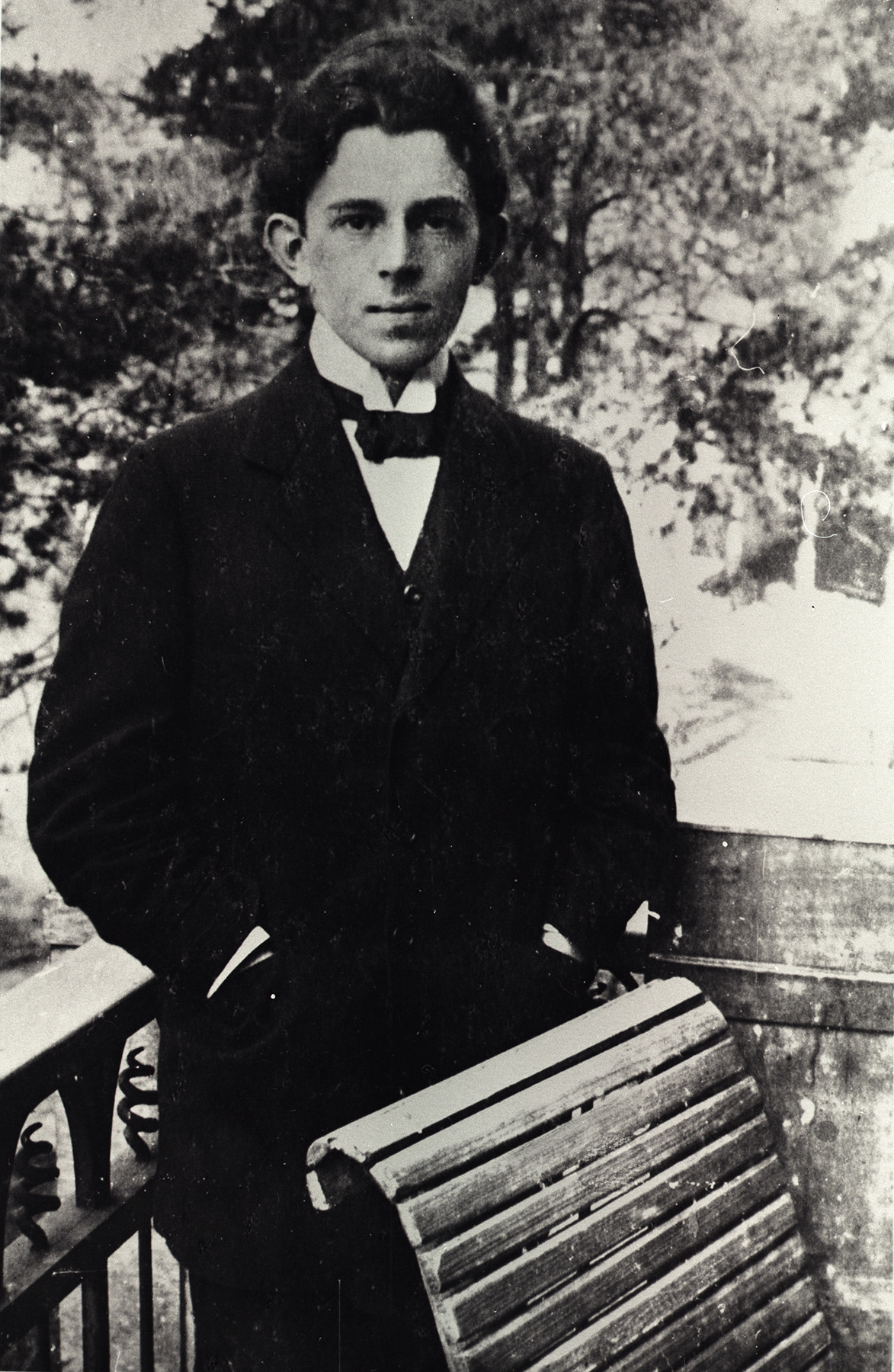

Osip Mandelstam was born into a Jewish merchant family in Warsaw and later moved to St. Petersburg where he received his secondary education at a prestigious school. He also studied at the Sorbonne and at Heidelberg University. He made his first steps as a poet in association with the Acmeist poets (Anna Akhmatova and Nikolay Gumilyov). He was fascinated by antiquity and by French poets Paul Verlaine, Charles Baudelaire, and François Villon, and had a brief affair with poet Marina Tsvetaeva.

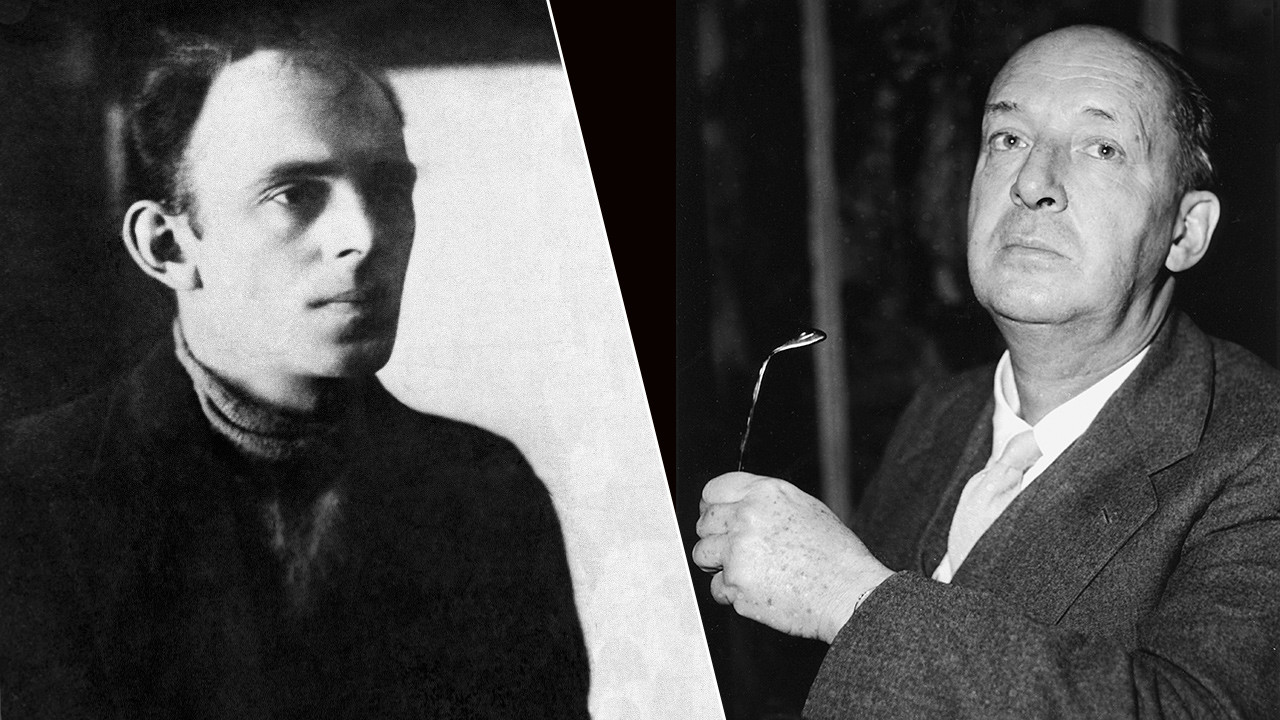

For many intellectuals in Russia today, two poets - Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) and Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996) - have acquired a nearly sacred status. Both are presented almost in the guise of Christian martyrs, as poets who suffered for their verse: One died at the hands of the authorities and the other was forced to emigrate. And yet, if the life of Brodsky was rather successful - he was awarded the Nobel prize and recognized around the world - the no less brilliant Mandelstam fell victim to political repression and sank into oblivion for many years.

2. He is the author of the most famous anti-Stalin verse

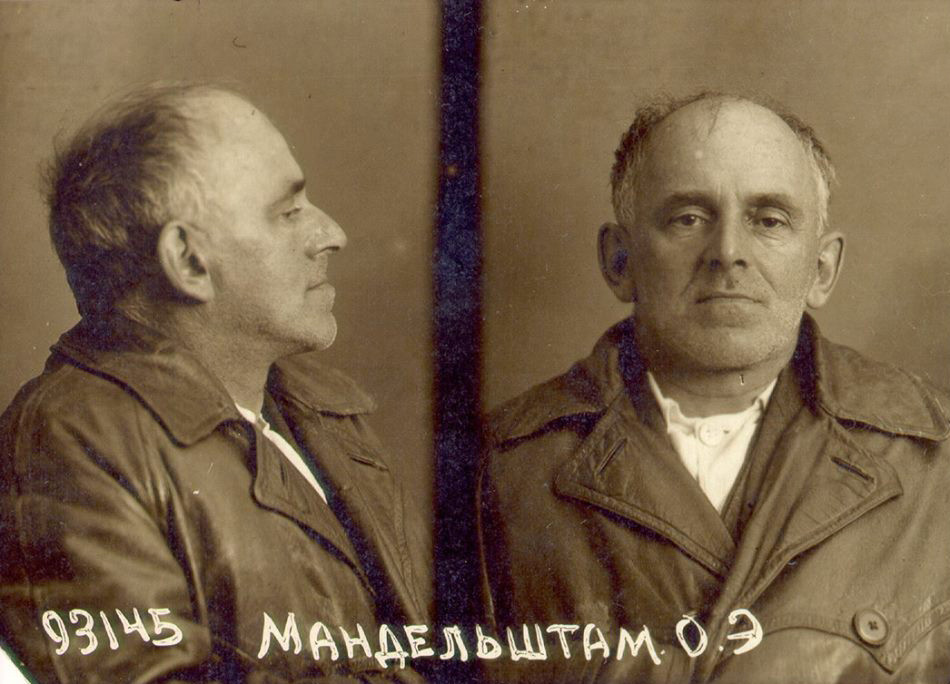

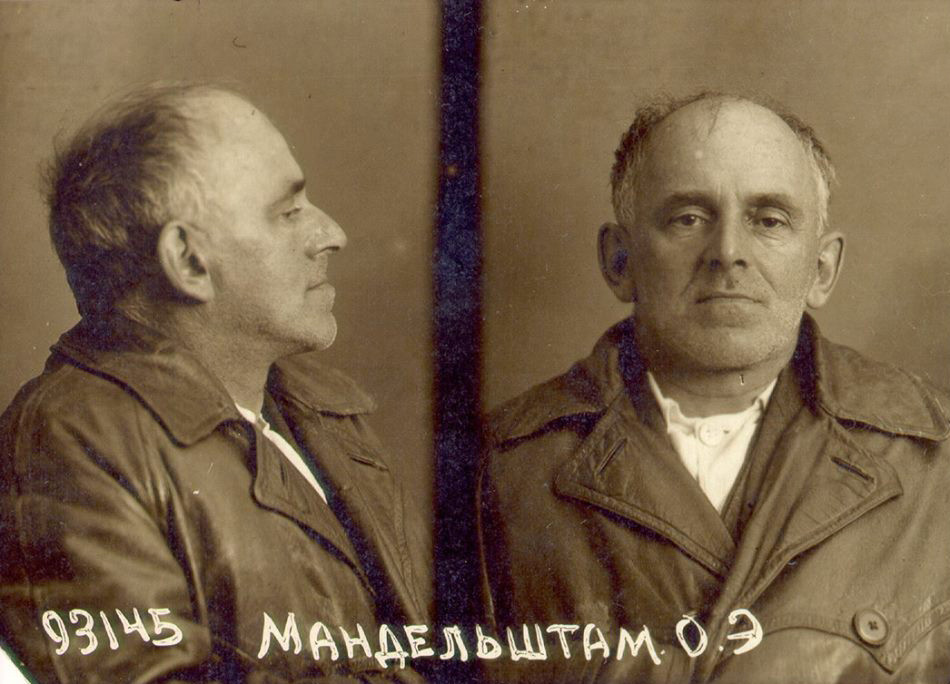

NKVD profile photo of Mandelstam

Public Domain

In 1933, at the height of Stalin’s cult of personality, Mandelstam wrote the poem We live without feeling the country beneath us, which contained unthinkable criticism of Stalin. He calls the Great Leader the "Kremlin mountaineer" and accuses the authorities of ignoring ordinary people: "Our speech at ten paces inaudible." He describes the entourage of the Leader of the Peoples as a "rabble" who merely carry out orders. [The above quotes are taken from the translation by David McDuff].

It goes without saying that the poem was never published either in Mandelstam's lifetime or for a long time afterwards. It was dangerous even to write it down: Mandelstam recited it to friends, but Boris Pasternak called it suicidal and asked him not to repeat it to anyone. The state security archives only have one surviving autographed copy.

Anyway, Mandelstam was prepared for the most terrible outcome, although at first he was only exiled to Voronezh. The poet was arrested in 1938 before dying in a transit camp in the Far East.

And yet, the poem has survived: It was published in the West in 1963 in the Mosty [Bridges] journal, to which it was passed by literary historian Yulian Oksman (thanks to him, many verses of the poets of the Silver Age not published in the Soviet period are extant). That was the beginning of Mandelstam's rise to fame in the West.

3. He is regarded as one of the most significant poets of the Silver Age

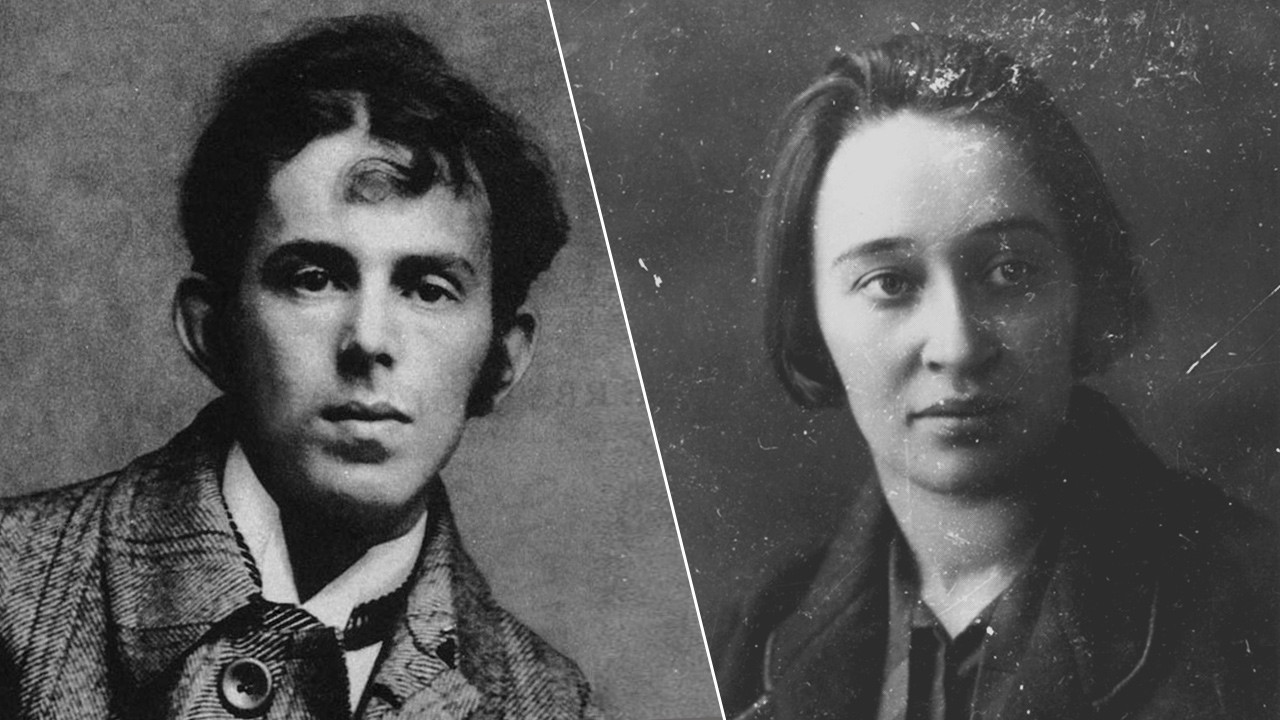

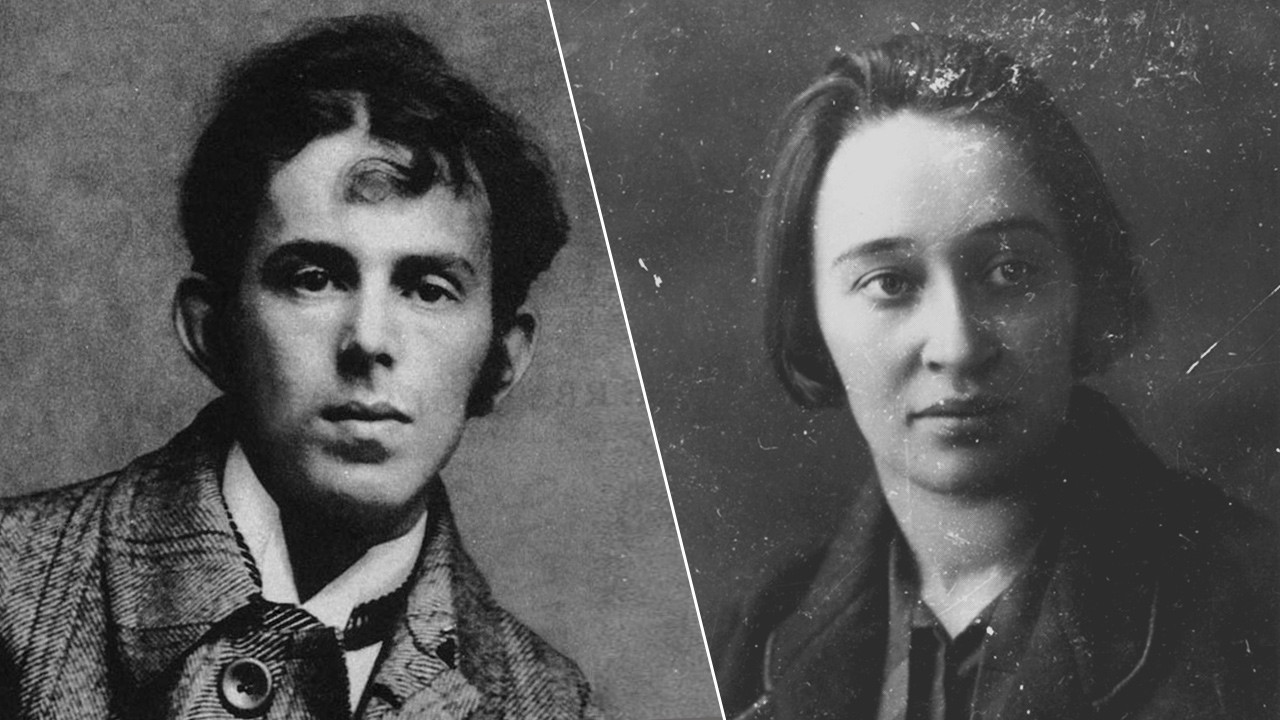

Mandelstam and his wife Nadezhda

Getty Images

Nowadays Mandelstam is considered one of the most important poets of the 20th century, although this was not always the case. During his lifetime he was in the shadow of other poets of the Silver Age - above all, Alexander Blok, according to literary historian and Mandelstam biographer Oleg Lekmanov. Then his poems were banned for many years, until the publication of We live without feeling the country beneath us helped revive interest in him.

However, the main interest in Mandelstam was fueled by two books of memoirs by his wife Nadezhda which came out in 1970. In the West, more copies of the memoirs were published than of Mandelstam's poems. In her memoirs, she describes not only her husband’s life but also provides portraits of many of his contemporaries.

4. He was one of the most complex poets in the world

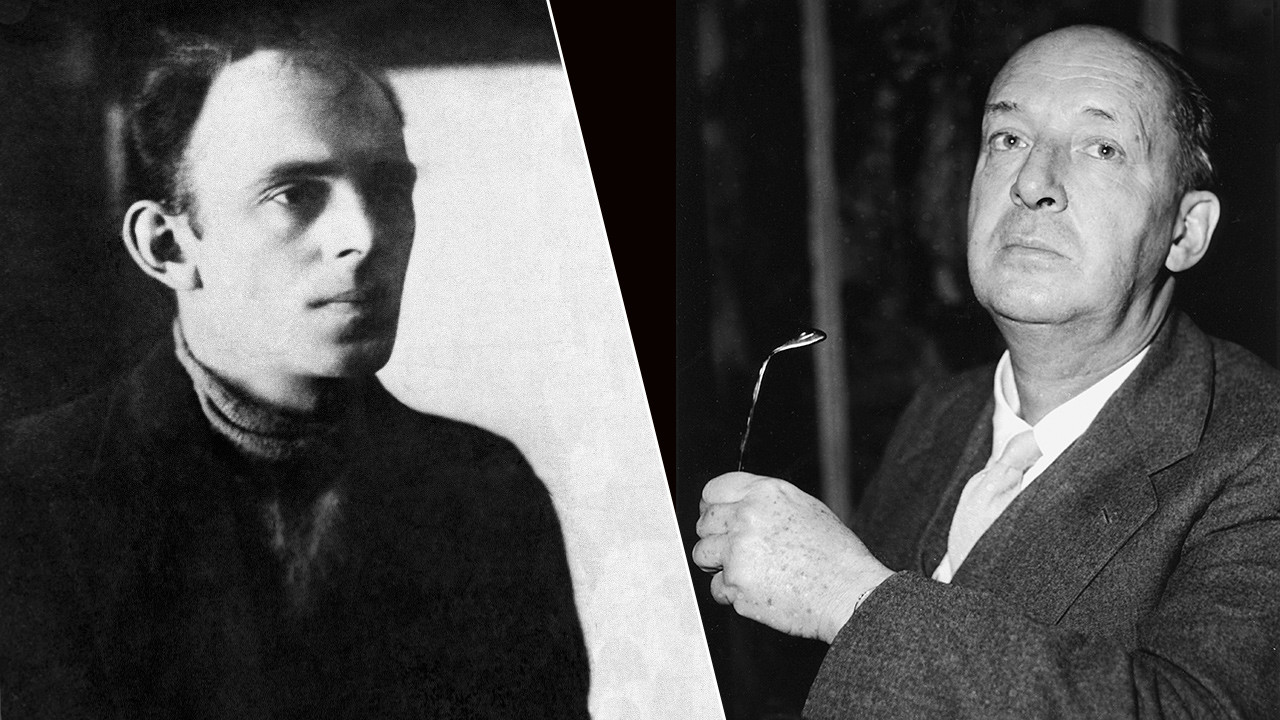

L: Mandelstam, R: Nabokov

TASS, Global Look Press

Western academics began to seriously study Mandelstam after a collection of his poetry was published in the U.S. At the time Kirill Taranovsky, a linguist and literary scholar of Russian origin and lecturer at Harvard University, formulated the term "subtext." It means that the key to the incomprehensible passages in the poems of Mandelstam (as well as Akhmatova) lies in the texts of other poets - those of antiquity, or the French poets, or Pushkin and his contemporaries. By referring to these texts, we gain new shades of meaning.

Mandelstam has been studied a lot, but there is still no academic collection of his writings or a separate book of accounts about the poet by his contemporaries.

The greatness of Mandelstam was recognized even by Vladimir Nabokov who, despised practically everyone.

5. He wrote one of the best love poems in history

Moscow, 1933-1934. R-L: Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Maria Petrovykh, Osip's father Emil, wife Nadezhda and brother Alexander.

Sputnik

Dear mistress of guilty glances... Great poet Anna Akhmatova described it as the "best love poem of the 20th century."

The poem is full of the kind of subtexts mentioned above: Some find parallels in it with Biblical stories involving Mary and fish as symbols of Christ; or oriental fairy tales in which fish were metaphors for sex.

Dear mistress of guilty glances,

glum owner of narrow shoulders,

quieted by men’s dangerous dispositions

she no longer sounds, drowned speech.

Odd fish travel, flashing their fins,

gills inflated. Here, you take them,

with their silently opening mouths,

feed them the half-bread of your flesh.

We are not fish, red and golden,

our sisterly fashion is this:

thin ribs framing a warm body

and the useless, moist glow of eyes.

The brows’ arch marks a risky path.

Must I, like a janissary, love

this miniature, bird-red mouth,

your lips’ pitiful crescent month?

Don’t rail, my dear Turkish girl.

I would be sewn up with you in a sack,

your dark language I would swallow,

on fire water for you I would get drunk.

You, Maria, are an aide to the dying.

We must warn death, fall asleep.

I stand before the hard threshold.

Go away. Please, go. Stay a bit. (1934)

(Translated by Alex Cigale)

If you know Russian, watch Roman Liberov's animated film about Mandelstam, "Save My Speech Forever" below.

READ MORE: 5 reasons you must know Alexander Solzhenitsyn

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.