OPINION: Why do Russians fight about the ‘Cult of Bread’ (and why it’s stupid)?

Current Russia is a relatively easy place to live in. This presents us with an identity problem. Today, more than ever, our culture is dependant on “skrepy” (pillars) to unite us and give us a modern sense of nationhood. These pillars can be your religion, your attitude toward elders, motherhood and so on. For Russia, “bonding through adversity of hunger” was a unifying pillar unto itself. Today, Russians are no longer just “surviving.” However, in the absence of strong reasons to update our past identity, its cult-like character traits get carried over.

The 'cult of bread'

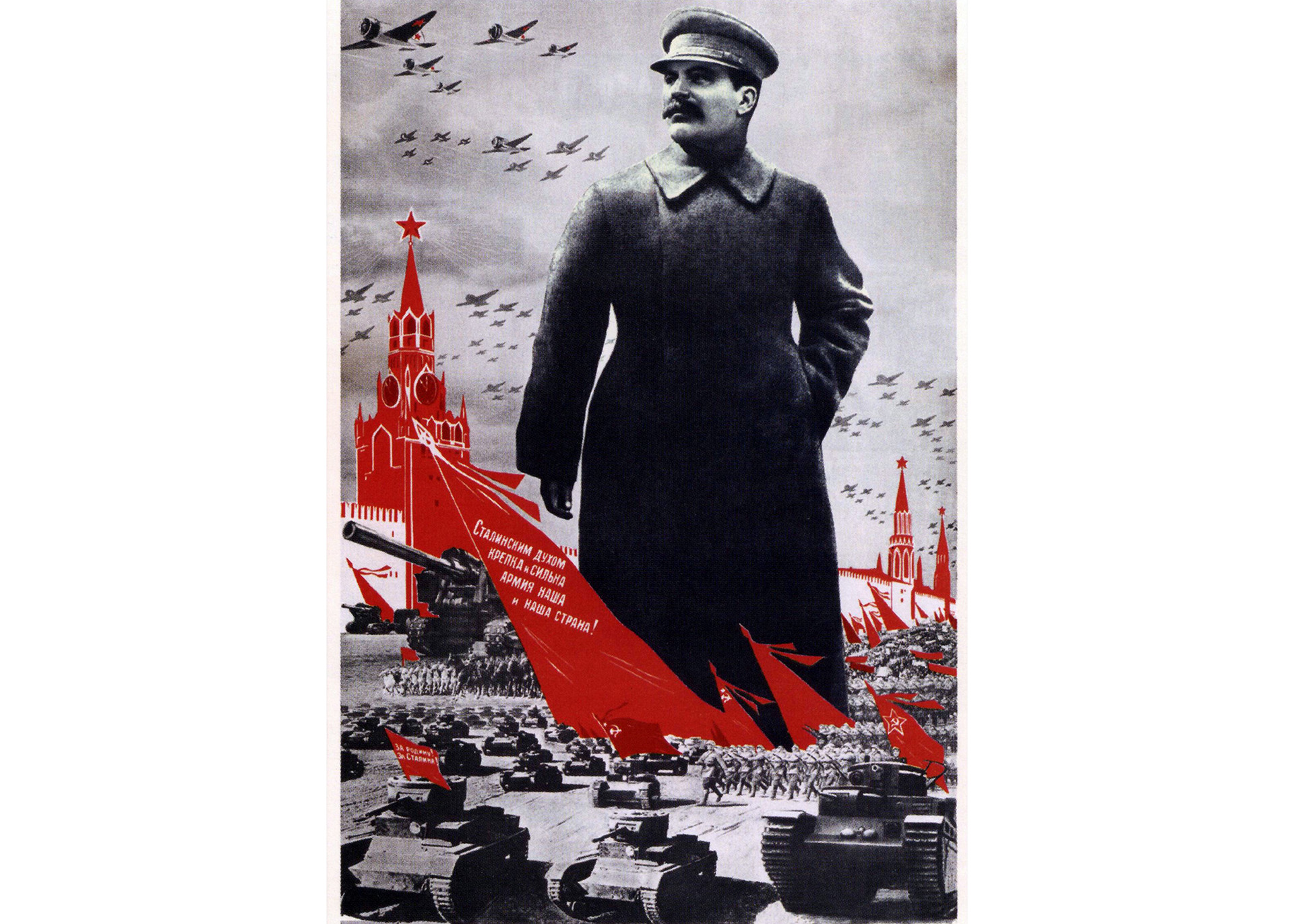

Poems, songs and propaganda posters - a whole system of morality based exclusively on the respect for bread was set up in the 1940s. As a child, you could be punished by parents or scolded in public for appearing to treat a piece of bread with disrespect.

Those school teachers must be in their seventies today, but that hardly makes a difference. I regularly get into arguments with my own mother when visiting once a week for lunch. My bread consumption has decreased over the years, but serving bread with every meal is an incredibly tough habit to shake: she gives me more bread than I ever need - so that I don’t go hungry, and I proceed to criticize her for giving me too much, because I cannot stomach the sight of an unfinished piece of bread. And so it perpetuates through the years.

Here’s the thing: our family was never hungry. We are simply acting out our culture - like a play. In Russia, stuffing your children like they’re a Thanksgiving turkey is like bowing in Japan. It’s custom. But that custom isn’t rooted in some age-old belief. It’s an invented tradition.

The grandparents of my generation remember the days of hunger they experienced as children of the War. Until the early 1950s, the Soviet Union was in damage control mode. Among other things, there was the difficult task of tackling food shortages, and it was imperative that the Soviet government firmly establish itself as the sole saviour of its people. It was about divorcing society from all forms of belief but those in the primacy of the State. This wasn’t difficult to do because the hunger was real, and the state was uniquely poised to solve it.

During war time, Soviet citizens were given bread cards. The hunger was so rampant - especially in Leningrad (present-day St.Petersburg) during the Blockade, that bread was synonymous with survival. Potatoe, for example, never gained that status. Neither did cabbage. To have bread meant you were living in a rich land - something the government would count on for the remainder of the century as it rallied the masses behind it.

READ MORE: OPINION: Why is Russia so damn 'depressing?'

Being anti-religious didn’t mean the Soviet Union wasn’t religious by nature. Although by the time WWII struck, organized religious expression was back on the menu, even before then, the Russians were always adept at organizing around cult-like beliefs, where something by its nature ordinary was imbued with mystical properties in times of hardship. For example, the heavy losses sustained by Russia in the First World War had created a sort of ‘cult of death’, based on embracing sacrifice for the greater good. Joseph Stalin’s personality cult is also very well known. It was in that Russia that our Bread Cult was born - although agricultural worship itself was nothing new, we’d been doing it for thousands of years.

In other words, Soviet Union was the religion.

Stalin’s time is very difficult to discuss with any kind of unbiased rigor. While the man is irrefutably responsible for tens of millions of deaths, he is also considered to be behind the incredible growth spurt that brought the country back from the brink of oblivion. When you’re the biggest country in the world, and you’re also still largely agrarian and illiterate, any idea will do, because you need a miracle.

Today, one side remembers the inhumane collectivization; the other remembers that Stalin got results with his rapid program of industrialization. Both are true. But there’s also a third set of people arguing - one that never even lived in the USSR.

Soviet religiousness was poisonously hypocritical

The bread cult of the 1940s and the accompanying ad campaign that lasted for a half-century afterwards had firmly become etched in the minds of people. So firmly, they still can’t agree on what was happening. It’s not the bread cult that is disputed - it is how it was implemented.

People of different ages tend to give different responses: some will remember being saved by Soviet initiatives - because “you had it worse during tsarism, so, shut up and eat what you’re given.” Their children, born in the 1950s, will remember the hypocrisy and the wasteful attitudes taking place in the aftermath of Stalin’s badly overseen - and absolutely inhumane - collectivization programs that claimed up to 12 million Soviet lives.

Many people failed to be swayed by infomercials about hungry African children - as well as the hunger on their own streets. Often, bread that went a little stale would be given to dogs, or otherwise thrown out. Some of the poorer quality bread produced by village cooperatives would even be bought expressly as animal feed. Hardly what you’d do to a sacred object.

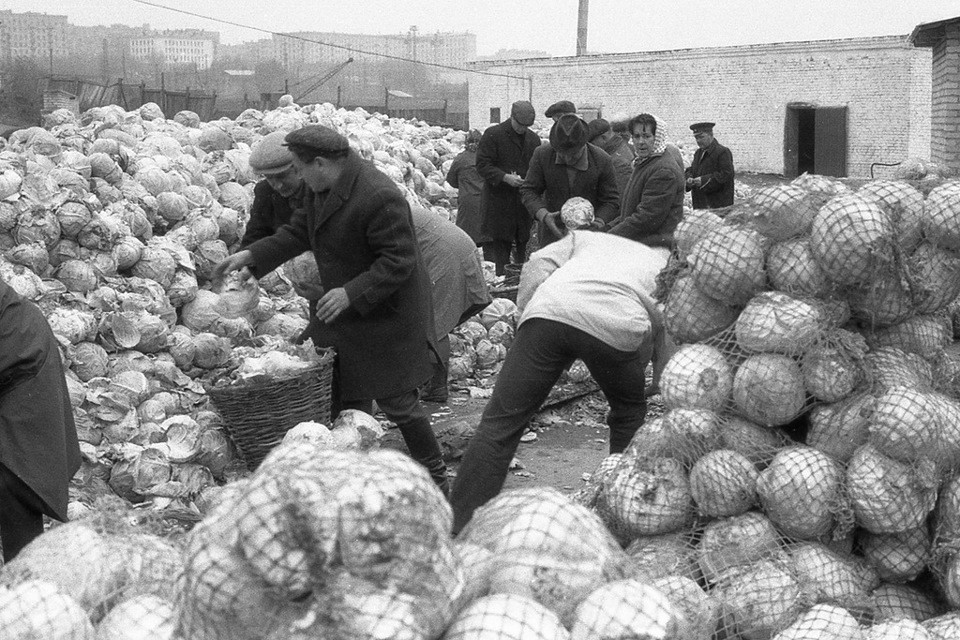

Meanwhile, heaps of cabbages and potatoes lay rotting in markets: there was comparative ignorance of those foods’ nutritional value because they didn’t get their own religious cult, compared to His Royal Majesty Bread. “Bread rules over all,” we used to say - because bread came to save us at the worst of times. And we had more bad times than good.

Even though the hunger was all but eradicated by the start of the 1950s, the bread zombification would continue into the early 1990s. My own school building was chock-full of Soviet symbolism for another decade, until - slowly - the bread poems, the Yuri Gagarin murals, the social-realist wall frescoes of pioneers marching toward a brighter future were beginning to be painted over.

Then why are we still living the aftermath?

People argue over interpretations of the past because it helps us better understand who we are and where we are headed. But it is hard to do when the past was literally 30 years ago, and we no longer have any use for its symbolism.

Bread was never that nutritious, and its association with hunger was always a sort of agrarian PR - a problem for the state to solve.

Mere weeks ago, in Novgorod, citizens went head to head because of a Christmas tree that a local bakery had made of loaves of white bread, and set up at the entrance. Newspapers reported people posting messages such as “Hideous”; “unconscionable!”' “Take this horror down, now!” Others shot back with stuff like “It’s just bread” or “it’s not even real.” Either way, the story proved contentious and ended up in many papers. Somebody wrote in a local group: “It doesn’t matter - even if the bread was stale, this is no way to treat it.” This goes to show that bread’s significance still goes beyond just being food.

Elsewhere, two bloggers insult each other over how the bread cult is to be remembered. As is predicted, the older of the two believes the younger to be an “anti-sovetchik” because he dared to use the topic of bread propaganda as a tool to take a stab at the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, both have solid points, but their arguments read exactly like the ones fit for their age. What’s funnier - the older of the two wasn’t even alive during the worst years: he was born sometime in the mid 1950s, so would have felt as little physical hunger as the younger blogger he sought to diminish.

Until the Soviet generation passes, there will be little reason for Russians to dispense with Soviet symbolism. Quarrels about history and “what actually happened” are in themselves ahistorical in nature. Especially those of young people that love to argue about a country they’ve never lived in. Could it be because the Soviet Union - for all its sins - was the kind of colossal undertaking that modern Russians will never truly grasp? It certainly could be - which would explain why history gets treated so exotically: the grandness of Soviet attempts to rebuild - even those that we get wrong - are still more exciting to us than current reality. Today, we neither fight for survival, nor dream about the future.

The Soviets used to be miserable, but miserable together. The new Russians laugh at the old Russians’ obsession with bread. At least the latter had something. New Russians have no new cultural symbols. We are just globalized Soviet culture dealers.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox