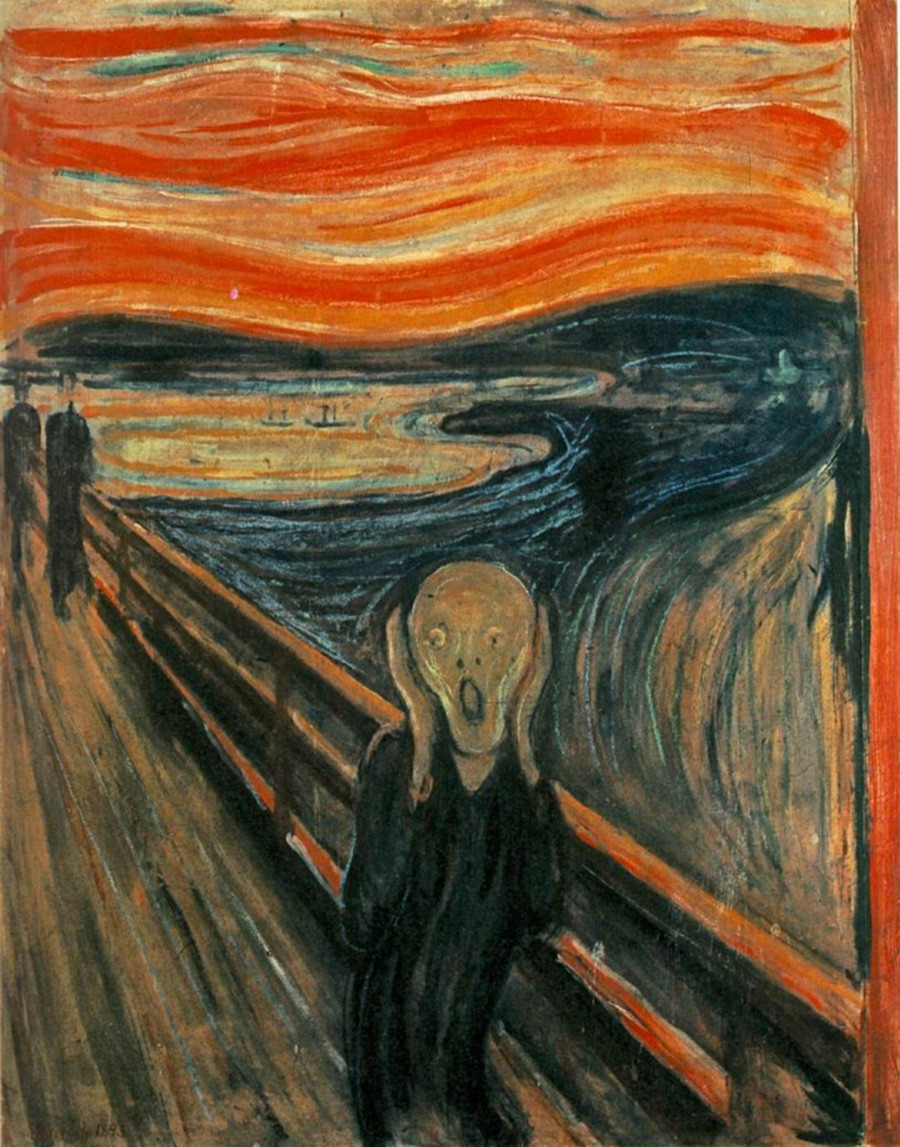

In April, Russia’s first ever major exhibition of one of Norway’s most famous sons, Edvard Munch, opens at the Tretyakov Gallery after several years of negotiations with the Munch Museum in Oslo. Although relatively few of his paintings are known in Russia, Munch’s work has a greater connection with Russia than one might imagine. His idol and inspiration was Fyodor Dostoevsky, and the artist’s most famous piece The Scream looks as if it is possessed by one of Dostoevsky’s demons.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

National Gallery of NorwayThe director of the Tretyakov Gallery, Zelfira Tregulova, noted that Munch essentially did for art what Dostoevsky did for literature: “He turned the human soul inside out and peered into the abyss and the vortex of passions that rip people apart, revealing the complexity of human nature.”

The bohemian atmosphere of 1880s Oslo, of which the young Munch was part, consisted of creative anarchists who fed on the works of Dostoevsky, freshly translated into Norwegian.

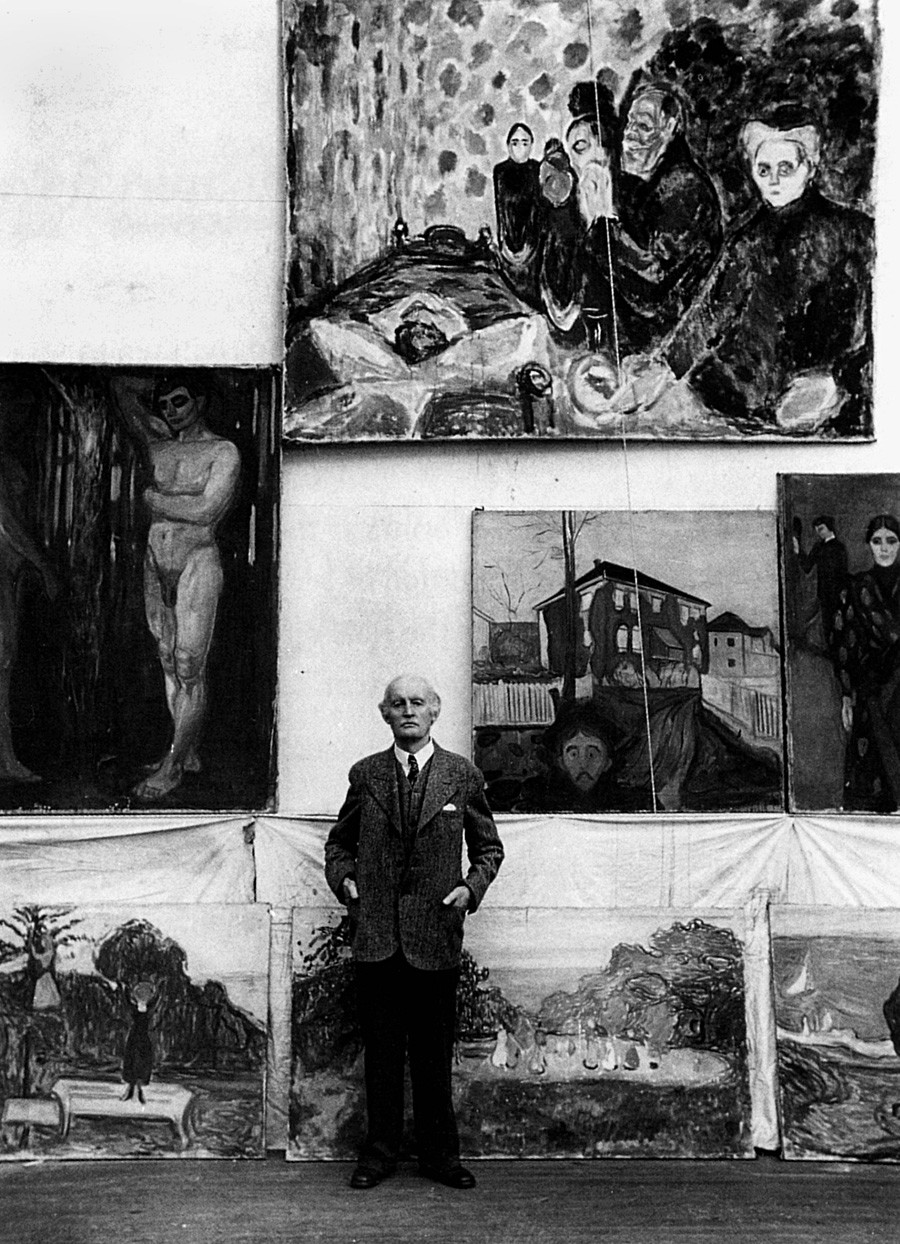

Edvard Munch in his workshop in Norway, 1938

Getty Images“Will anyone ever be able to describe those times?” We need Dostoevsky, or at least a mixture of Krogh [an artist, Munch’s mentor], Jeager [a scandalous anarchist writer], and perhaps myself to describe the wretched existence in Christiania [the old name for Oslo] as convincingly as Dostoevsky’s depiction of a Siberian town—not only then, but now as well,” wrote Munch.

A little-known work of Dostoevsky (or at least overshadowed by the later novels), A Gentle Creature had a profound influence on Munch. It tells the story of the suicide of an unhappy girl who, out of poverty, marries a moneylender she despises.

Experts believe that one of Munch’s most famous self-portraits Between the Clock and the Bed, which shows a nude female figure, might easily be an illustration for A Gentle Creature.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed, 1940-1943

Munch Museum in OsloMunch and Dostoevsky shared an artistic weakness for sick, poverty-stricken wenches. Another of Munch’s most famous paintings, The Sick Child, which prompted a hail of indignation from critics for its “incompleteness,” was a reflection of the artist’s grief over the death of his beloved sister from tuberculosis.

Edvard Munch. The Sick Child, 1885-1886

National Gallery of Norway“I am not entirely sure why I became attached to her, perhaps because she was always ill... If she had been lame or hunchbacked as well, I think I would have loved her even more...” says Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment.

Munch biographer Rolf Stenersen describes how the idiosyncratic artist considered his paintings to be his own children and showed tough love to those that didn’t turn out quite right. Such pictures he exhibited outside in rain, wind, and snow, and returned them indoors only after some time. It is known for a fact that this happened to the painting Separation, which suffered greatly as a consequence. Stains, smudges, and traces of bird droppings became part of the picture.

Edvard Munch. Separation, 1896

Munch Museum in OsloThis strange method Munch called hestekur (translated as “horse treatment”). Experts believe it to be a reference to Raskolnikov’s dream, in which the protagonist, transported back to childhood, witnesses a peasant beating an old nag just because it is “mine.” Soon the crowd joins in with chants of “Flog it to death!”

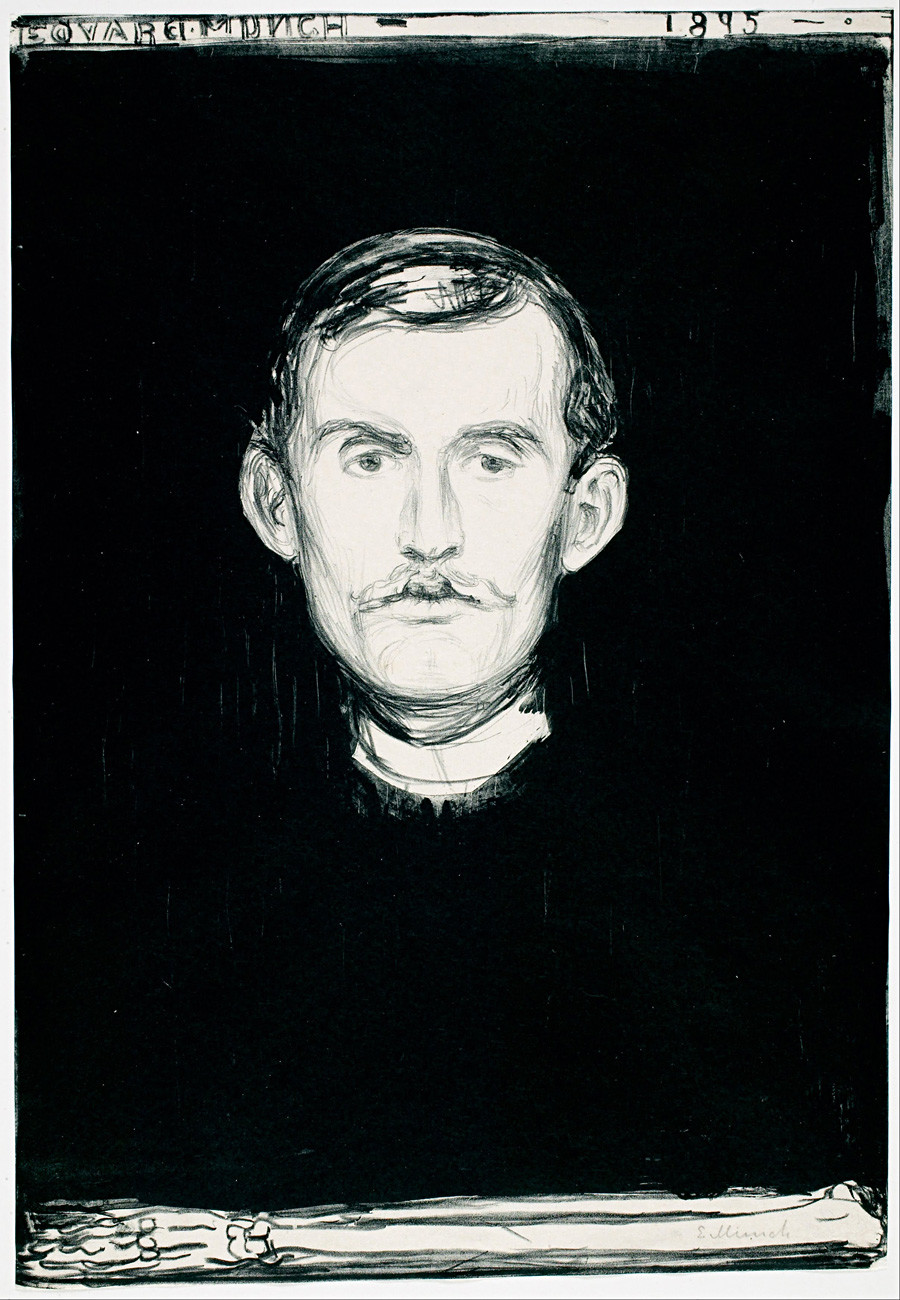

Edvard Munk, Self-Portrait

Munch Museum in OsloMunch created what might these days be described as fan art—artwork created by fans of a particular work. In one of his numerous self-portraits, Munch depicts himself with a skeleton hand. This work is said to have been inspired by a portrait of Dostoevsky made using a similar technique by Swiss artist Felix Vallotton.

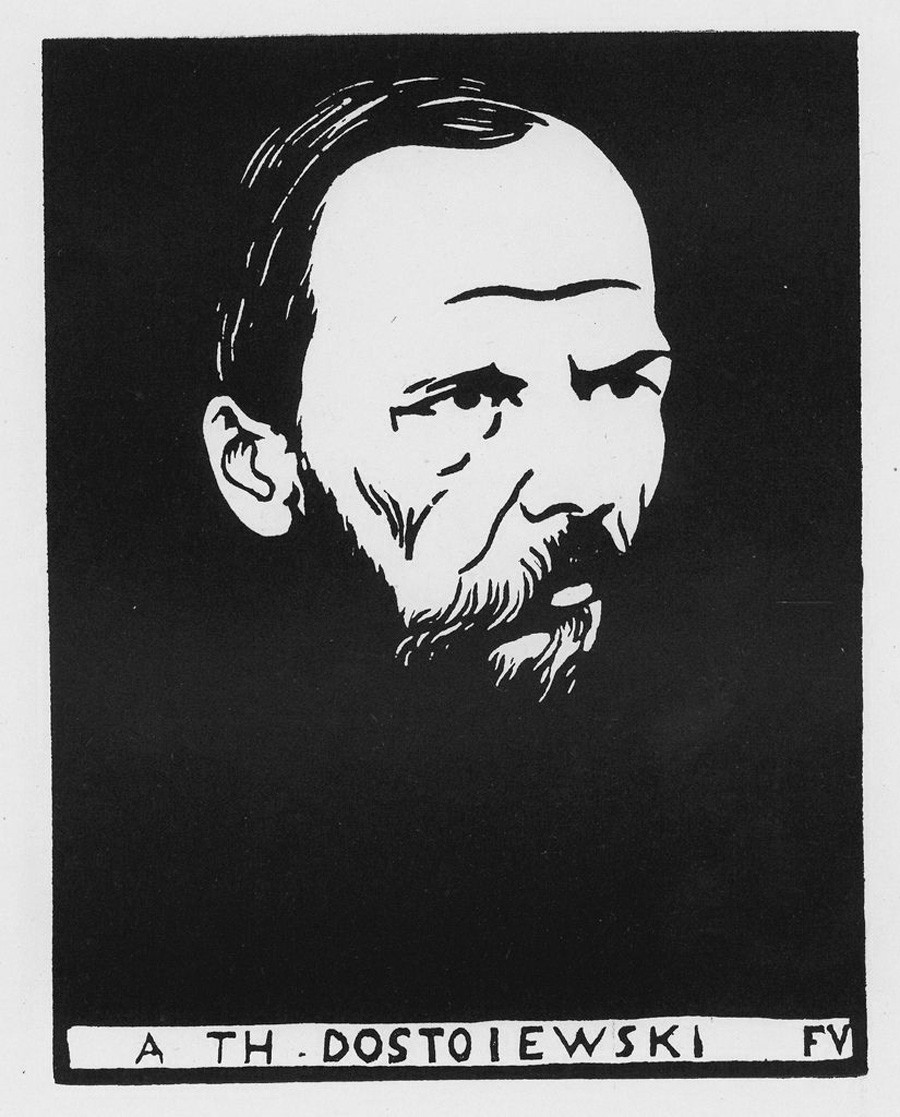

Félix Vallotton. Portrait of Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Foundation Félix VallottonOn display at the exhibition, there is a small volume that belonged to the artist. It is called Djasvlene, the Norwegian title of Dostoevsky’s novel Demons. It was this book that Munch had on his bedside table on being found dead at his country estate, not far from Oslo, in 1944.

Russia Beyond would like to thank Anastasia Chetverikov, culture expert, journalist, “Direct Speech” (Pryamaya Rech) lecturer, author, and host of the podcast “Art for Rebel guys,” for her assistance in preparing the material.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox