When you have lots of opportunities to entertain yourself, reading isn't always the first choice.

Irina BaranovaAccording to a global study on book reading, which was conducted by GfK in 2017, 59% of Russians read every day or at least once a week – that’s second place in the world after China. This fact remains doubtful, however, (it is based on people’s answers only), but if it is correct, such a large number of readers hardly surprises anyone in Russia. Historically, this country has always been literature-centric: in Russia, as Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote, “a poet is more than just a poet.” The same goes with those who write in prose.

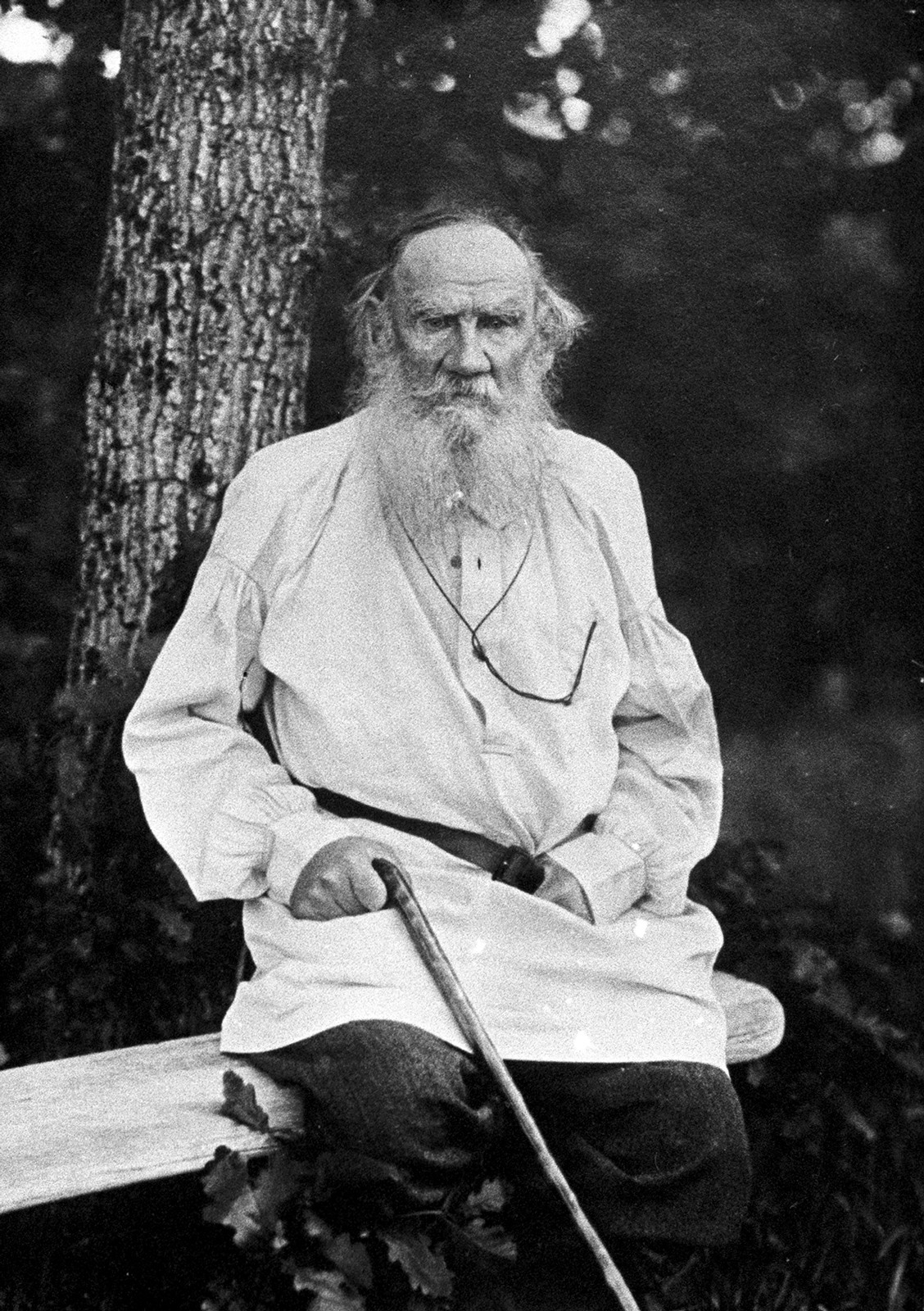

Take Leo Tolstoy. In the 1900s he was as big as The Beatles in the 1960s, or Beyoncé today - perhaps more popular than the Emperor himself. After the author confronted the Orthodox Church and young emperor Nicholas II in 1901, demanding equality and human rights for peasants, publisher Alexey Suvorin wrote: “We have two tsars: Nicholas II and Leo Tolstoy. Who is stronger? Nicholas II can do nothing about Tolstoy, he cannot shake his throne – but Tolstoy shakes his dynasty’s throne.”

Of course, Tolstoy’s case was very peculiar: since the 1880s, he had become more of a philosopher and a public figure than a fiction writer. Nevertheless, other literature giants of the 19th-20th century – Feodor Dostoevsky, Ivan Turgenev, Anton Chekhov, Maxim Gorky and so on – also impacted Russian public opinion with their humanistic novels, which was certainly more influential than any tsarist minister and his orders. That’s when Russia’s obsession with literature started.

Leo Tolstoy dominated Russia's cultural and social life in the early 20th century.

Sputnik“In the 18th to 20th centuries, public life in Russia was all about literature,” explains Lev Oborin, a poet and literary critic. While in the West monarchs were slowly giving up power to parliamentary systems, the Emperor enjoyed a monopoly on all forms of power – so the only place to criticize the powers-that-be was on the pages of a novel.

“Due to the absence of actual politics, writers became defenders of freedom, and enlighteners,” Oborin writes. They had no other choice but to write about the state of mind of ordinary Russians, the evils of serfdom, the strange nature of the Russian soul balancing between West and East, and so on – using metaphors and allegories to escape censorship.

Sadly, the vast majority of Russians didn’t know a thing about the intellectual struggle of their writers, as they couldn’t read. According to the national census of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, at least 60% of Russian adults were still illiterate in 1913. Only the Soviet government managed to provide its people with education – and make them read the great writers of the imperial period.

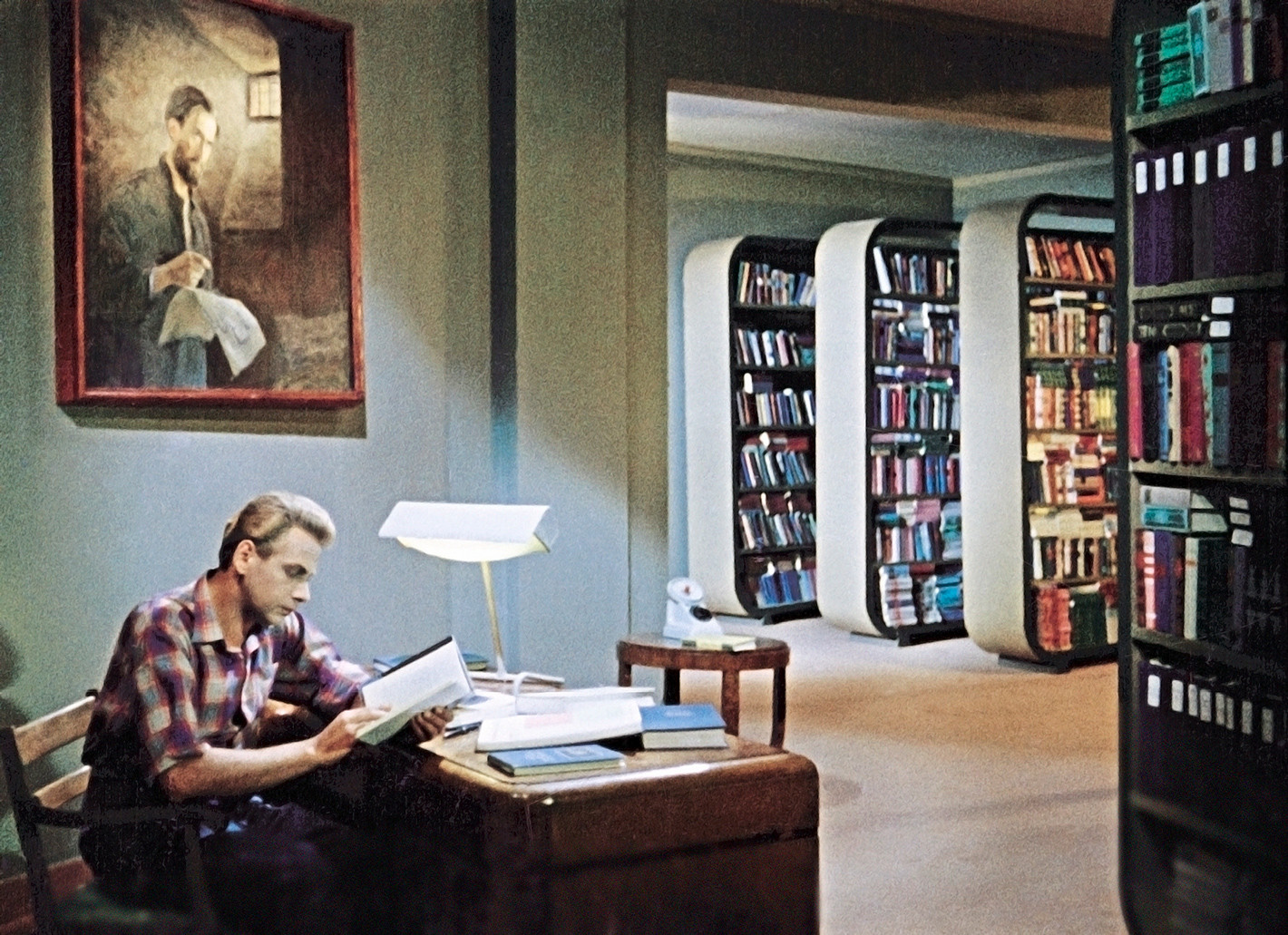

In the Soviet Russia, they surely printed a lot.

Mikhail Ozerskiy/SputnikThough brutal in terms of destroying their political rivals (and later, themselves), the fact is that the Bolsheviks improved the level of education: by 1939, 87% of Soviet citizens knew how to read and write, and the ever-controlling state did its best to provide them with all the literature they needed. As long as it fell in line with Marxist ideals.

The Soviet period was when the literary canon of the school program was formed – the one that we still have at school, though slightly changed today: Alexander Pushkin, Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, and so on. “Those writers were dissidents for the Tsarist regime… Soviet ideology benefitted from taking so-called ‘revolutionary democrats’ as their allies… even though not all of them were socialists,” explains Lev Oborin.

There were plenty of books in the USSR; paradoxically, it was quite hard to get the ones you actually wanted to read.

SputnikOf course, the state decided what to publish. Russian classics? Sure. Some non-too-provocative foreign prose (Hemingway, Remarque, Salinger)? Okay. But don’t forget the complete works of Lenin, Marx and Engels. And, for instance, memoirs of Leonid Brezhnev on his experience fighting in World War II –20 million copies were published in 1978.

The USSR spared no amount of paper on enormous print runs: by the 1980s, billions of copies were sold. “There were around 50 billion copies in home libraries [throughout the USSR],” writes historian Alexander Govorov in History of the Book. This provided the basis for the USSR calling itself ‘the nation that reads the most’ – a formula that is still very popular and pops up every time someone revels in nostalgia for the ‘great’ Soviet times.

The only problem was the total absence of choice. “The print runs grew bigger but public demand remained unsatisfied,” emphasizes Govorov. People wanted fiction and entertaining literature but the state kept on feeding them Marxist books, lying in piles in book shops, unsold.

“They published enough books in terms of quantity but what they published in the circumstances of ideological and economic diktat didn’t reflect what customers wanted to read,” Govorov sums up. In such circumstances, no one but literary critics cared about Leo Tolstoy anymore – people desired the freedom to read what they wanted.

Nowadays in Russia, like elsewhere, people always seem to be distracted, including from reading.

Moskva AgencyDuring perestroika in the late 1980s, which was followed by the USSR’s collapse, they got their chance. It is a long and quite a peculiar story of how the book market emerged and developed in contemporary Russia – but three decades on it exists like everywhere in the world. And even if Russians once were the nation that read the most, that’s no longer the case.

As we mentioned before, 2017 GfK’s research ranked Russia second in the world in the number of readers. But people from the Russian publishing industry doubt such an optimistic rating.

“We follow sales on the book market, and they [currently] are not growing in Russia,” said Yelena Solovyova, editor-in-chief of Book Industry magazine.

In fact, print runs have been slowly falling during the last 10 years: from 760 billion copies printed in 2008 to 432 billion in 2018. This is a very complicated matter to research, however, due to the growth of electronic book sales, as well as the completely unstudied pirate market.

Anyway, current Russian interest towards literature is stable, but future prospects are not encouraging – there is no Leo Tolstoy on the horizon and the years of Soviet megalomaniac printing have ended. Today, people prefer other types of entertainment: literature must compete with Netflix, YouTube and zillions of web pages, so the chances of victory are not good. But this is a global trend.

“All over the world, interest towards reading is declining, and Russia, unfortunately, is following the same trend,” admits literary critic Galina Yuzefovich. “But in recent years it became absolutely clear: reading has a stable and core audience that will never trade a book for other kinds of entertainment.”

So while Russia may be reading less than before, it is very unlikely that it will ever give up reading for good.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox