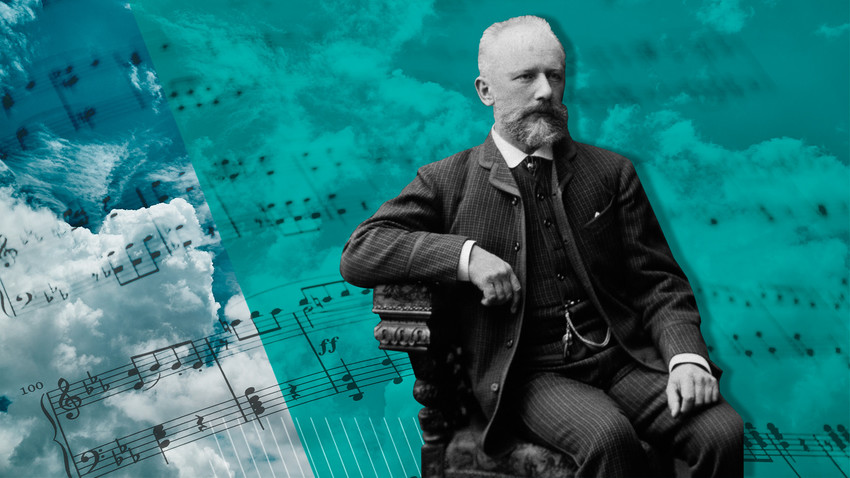

Ten operas, three ballets and seven symphonies, not to mention countless songs, concertos, cantatas, miniatures for piano, and a wide variety of music for orchestra and individual instruments—such is the enormous legacy Pyotr Tchaikovsky left in classical music. The great composer was active in the second half of the 19th century, which is regarded as the "golden age of Russian music."

Tchaikovsky family, 1848 (Peter is on the left).

Public DomainTchaikovsky was born in 1840 in Votkinsk, a town in the Urals where his father was posted from St. Petersburg to run the local ironworks. Incredibly, the plant still exists today.

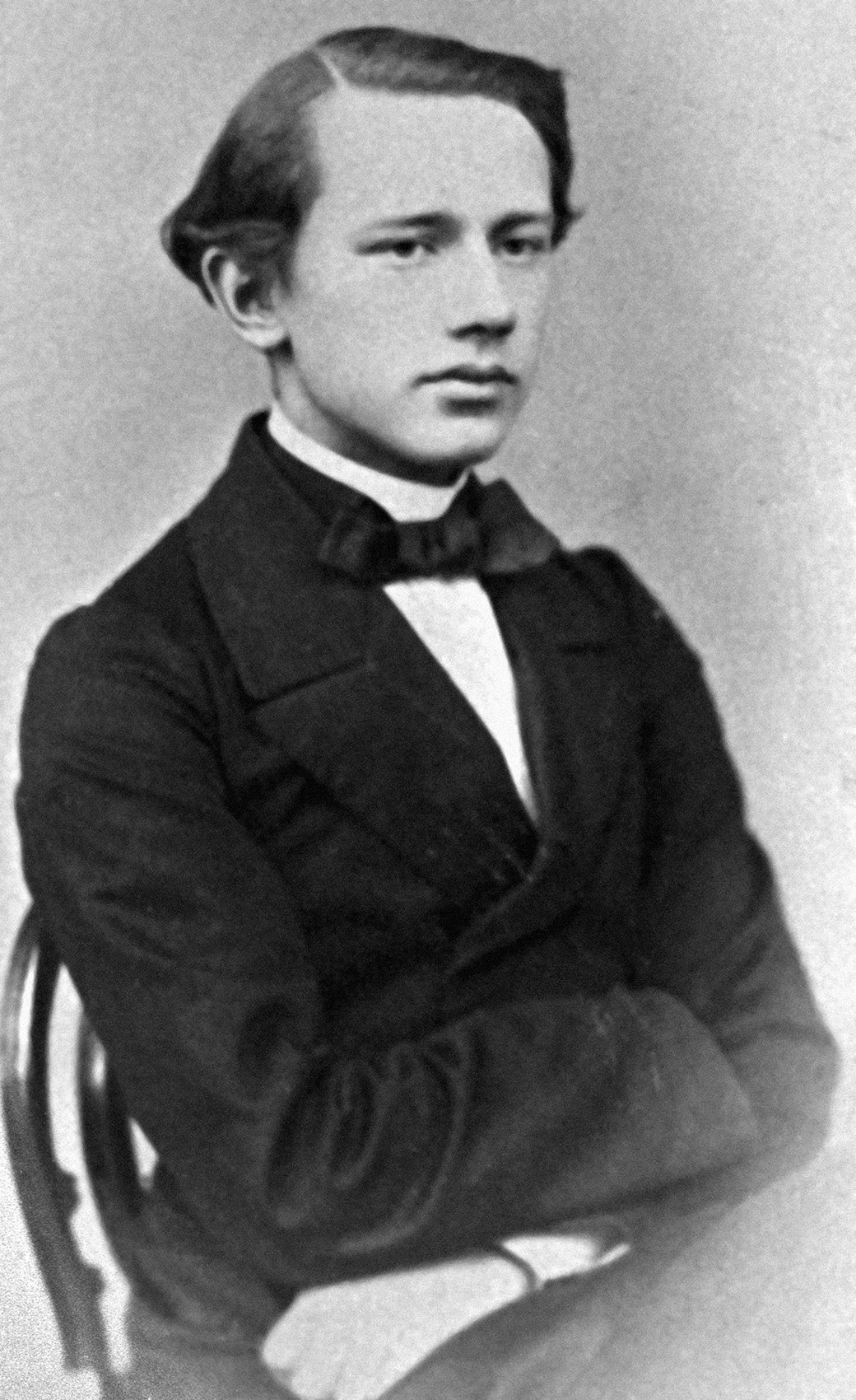

Tchaikovsky, 1859.

Public DomainMaking music, as well as composing short poems, was part of the education young Pyotr received at home. Furthermore, Tchaikovsky's parents had a deep love of music and cultivated this same attitude in their children. There was a curious instrument in the house: a small mechanical organ called an orchestrion that Pyotr loved to listen to as a child. The boy was particularly impressed by Mozart and wrote in his diary that it was, "thanks to him, I learned what music was."

Tchaikovsky, 1859. (the 7th on the left, the 1st row).

Public DomainA young serf named Maria Palchikova gave piano lessons to the boy. There is still no agreement among Tchaikovsky scholars as to how she learned to read music herself—whether she did so on her own or the noble woman she belonged to had spotted the girl's potential and paid for lessons.

When Tchaikovsky was 10, he and his mother moved to St. Petersburg, where he soon enlisted at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence.

1860s.

SputnikLife in St. Petersburg was certainly very different than in the provinces. Little Pyotr was taken to the theater, which he adored, and it was there that he heard what a big orchestra sounded like for the first time.

His father hired a German named Rudolph Kündinger as a private piano tutor for Pyotr, and Kündinger began taking the boy to concerts. Ironically, Kündinger told Tchaikovsky's father that the boy had no special talent for music.

But Pyotr's fascination with music continued. After graduating from the jurisprudence school, he served at the Ministry of Justice, but the theater remained his passion. He became close friends with an Italian vocalist working in Russian theater and became a great admirer of Italian opera.

Despite Kündinger's dubious verdict about Tchaikovsky’s musical potential, his father suggested that Pyotr should have a musical education. And so at the age of 21 Tchaikovsky enrolled at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and studied composition.

In 1865, one of Tchaikovsky’s compositions, Characteristic Dances (later renamed Dances of the Hay Maidens), was performed publicly for the first time. Conducted by Johann Strauss II himself, it was warmly received. Following this, the Conservatory Orchestra performed one of his overtures for the Imperial Family at the Mikhailovsky Palace. Tchaikovsky himself conducted this time.

The end of 1860s.

Public DomainBut despite these advances, widespread recognition remained elusive. Tchaikovsky left the civil service to focus on music and, as a result, no longer had a stable income. This is how biographer Nina Berberova described that period: "There was no money, there were debts…Composition was not going well and at times it would seem that there was only one solution—the ministry department. Should he go back?"

On top of that, Tchaikovsky was left all alone St. Petersburg after his entire family returned to the Urals. According to Berberova, he even contemplated suicide.

Tchaikovsky graduated from the St. Petersburg Conservatory the next year and was invited to teach at the equivalent conservatory Moscow. The Moscow period finally brought him success, albeit as a music critic initially.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (right) with his brothers Modest and Anatoly and N.D. Kondratyev, 1875.

Getty ImagesHe became friends with The Five (also known as the Mighty Handful), a group of composers that included, among others, Modest Mussorgsky, Alexander Borodin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Tchaikovsky traveled around Europe where he naturally went to the theater a lot. He was in raptures over Georges Bizet's Carmen and completely smitten with Richard Wagner's music.

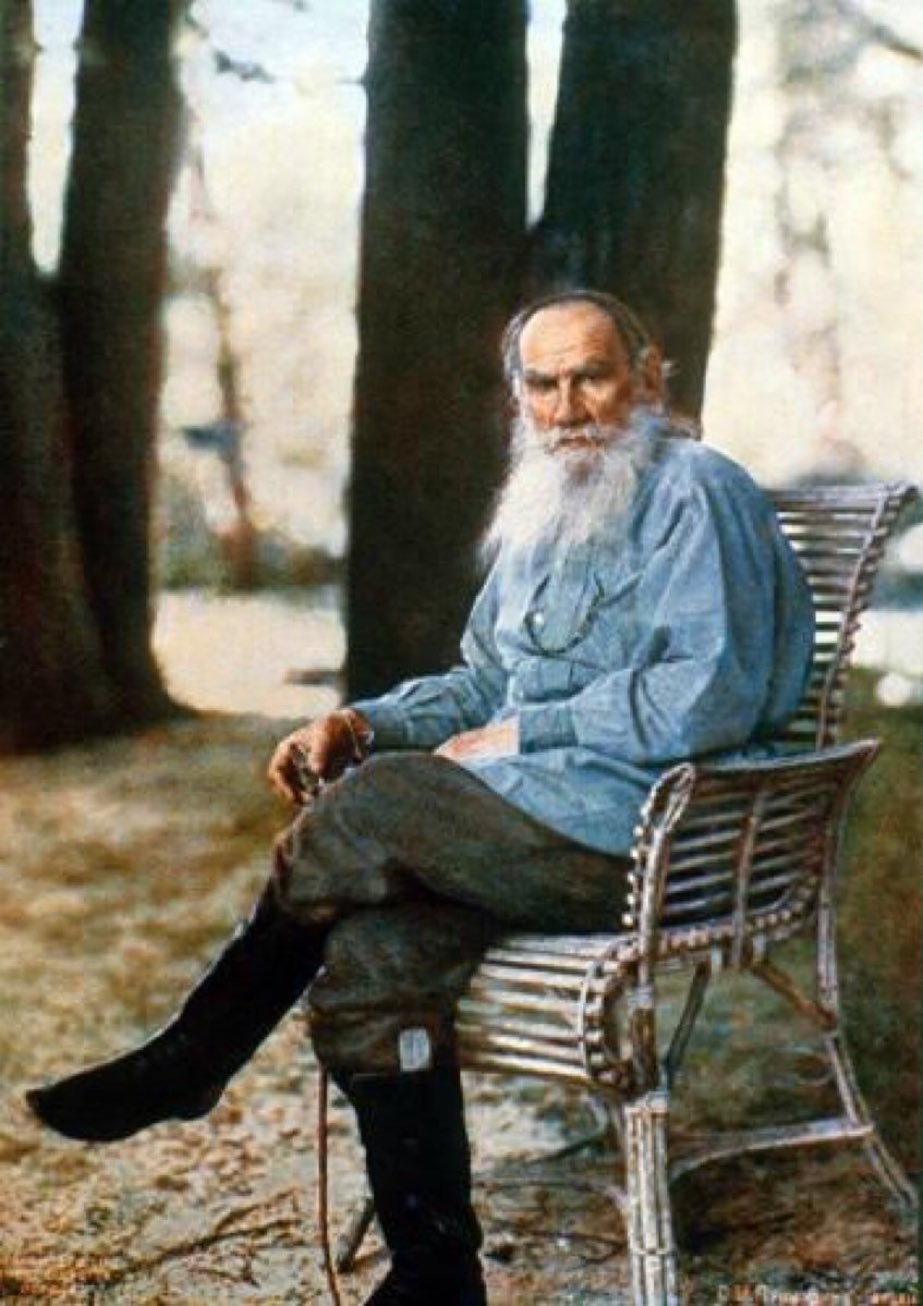

Leo Tolstoy.

Public DomainThere is an amusing story relating to the performance of Tchaikovsky's own works. It turned out that a small concert of Tchaikovsky's music had been organized at the Conservatory specially for Leo Tolstoy, but the doorman failed to recognize the great writer and wouldn’t let him in because since he was wearing valenki [felt boots]. Someone witnessed the scene and in the end the incident was resolved. Tolstoy sat in the first row and was moved to tears by the music of the fledgling composer.

In the 1870s, Tchaikovsky became fascinated with folklore. During this period, he wrote the music for Alexander Ostrovsky’s play The Snow Maiden; The Oprichnik, an opera set in the time of Ivan the Terrible; the opera Vakula the Smith (later reworked as Cherevichki and based on Nikolai Gogol’s story Christmas Eve); and one of his best known ballets, Swan Lake. Tchaikovsky also translated European opera librettos and works by Western music theorists.

The opera Eugene Onegin is what finally brought him real recognition. It premiered on the stage of the main Imperial Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg.

A scene from the Tchaikovsky's "Onegin" opera.

SputnikTchaikovsky advocated treating music composition as a craft that above all, according to the composer, should bring an income. "Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn and Schuman composed their immortal works in exactly the same way as a shoemaker makes his boots—i.e. day by day and for the most part to order," he wrote.

The composer's lifestyle changed and he began mingling with high society and spending time with members of the Imperial Family. He often sat in the royal box at the theater, where he was once introduced to Emperor Alexander III (who later paid in full for Tchaikovsky's funeral). The composer often travelled abroad, including to premieres of his own works. He even visited the United States and performed at the opening of Carnegie Hall in New York.

Odessa, 1893.

Public DomainDespite all this success, Tchaikovsky still didn't have his own house. He either stayed with friends or in hotels. Exhausted by the lifestyle of an eternal traveller, for the last two years of his life Tchaikovsky rented a house in Klin, a quiet town outside Moscow. Nowadays the house is a museum dedicated to the composer.

The house-museum of Tchaikovsky in Klin.

Vladimir Varfolomeev/FlickrTchaikovsky died quite suddenly after coming back to St. Petersburg and catching cholera. The disease fatefully pursued his entire family: His mother died of it and his father nearly died from it.

Tchaikovsky was not particularly happy in his personal life. In 1877, he married Antonina Milyukova, a musician and student at the Moscow Conservatory. They separated after just a few weeks. He had an affair with a French singer named Désirée Artôt and for many years corresponded with—and enjoyed the sponsorship and financial support from—Nadezhda von Meck, a patron of the arts.

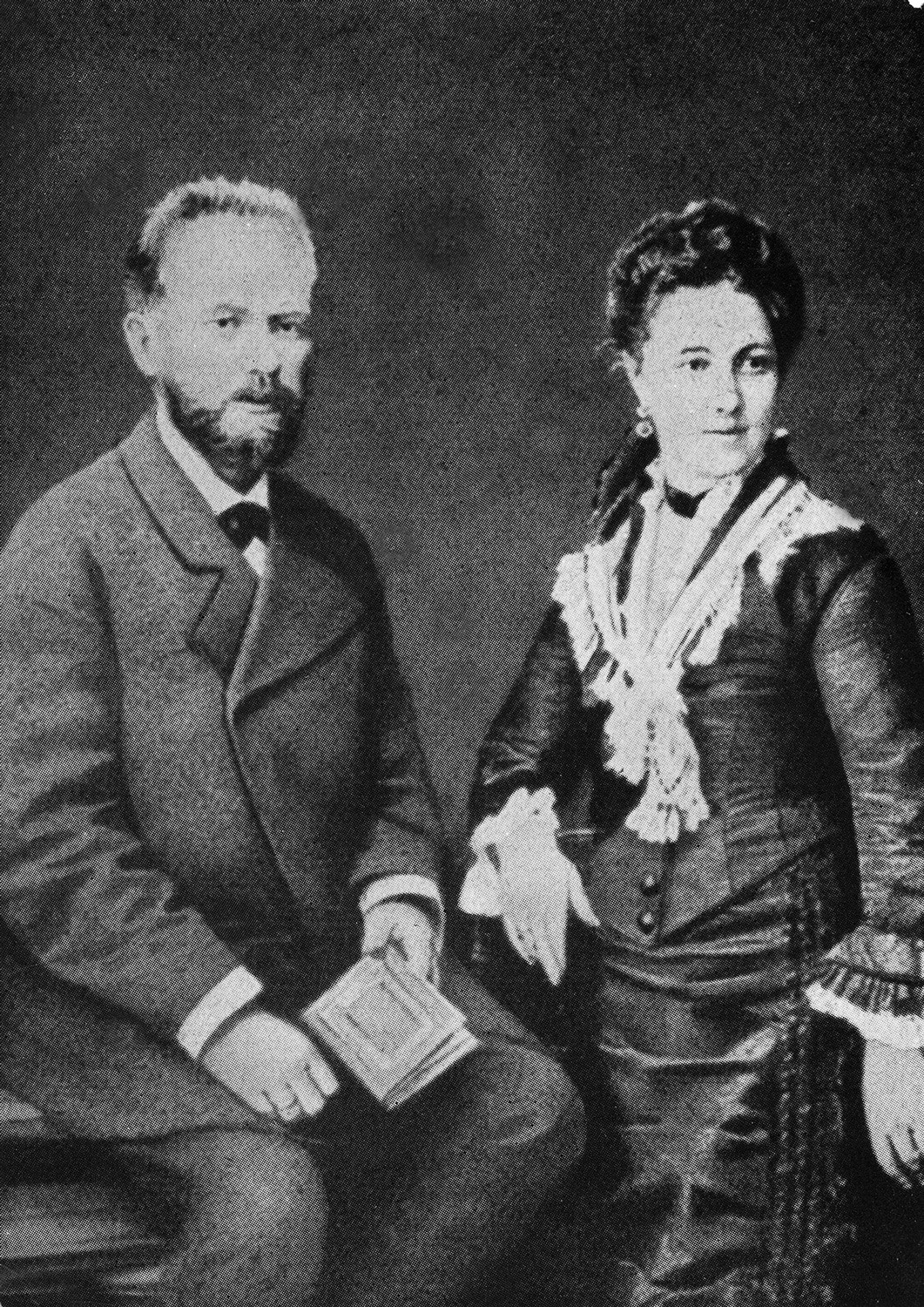

With his wife Antonina. 1877.

Getty ImagesAt the same time, Tchaikovsky was homosexual. His younger brother was as well and subsequently became the keeper of his legacy. It is believed that Tchaikovsky may have had his first sexual experiences back at private school in his younger years. He was later involved in several scandals related to being seen in the company of adolescent boys.

After his death, there were rumors that Tchaikovsky had committed suicide out of fear of being prosecuted for his homosexuality, but biographers refute this.

1893.

Public DomainDuring the Soviet period, information about Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality was suppressed even for researchers since homosexuality was illegal in the Soviet Union (like in any other countries at that moment), and the most famous composer couldn't be a criminal. In Russia, this aspect of Tchaikovsky's private life only came to be discussed relatively recently when a film biopic about his life was made.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox