All publishing houses in the USSR were state-owned, and every text had to get past the censor before appearing in print. This role was carried out by the Main Administration for Literary and Publishing Affairs (Glavlit), a kind of Orwellian Ministry of Truth.

In the days of Stalin a literary work that may have been published accidentally could be recognized as criminal retroactively, and the author and censor could get into serious trouble. In the opinion of many authors, however, under Stalin it was easier to comprehend where writers stood, and in extreme cases the tyrant himself became a critic of a controversial author. In the 1960s, the arbitrariness of the censors reached the point of absurdity, and in this regard, for many people that era was even more frightening, driving authors to despair.

There were many reasons why books were not published. According to the censors, books might be critical of the Soviet system (even in an allegorical or veiled form), or perhaps were not patriotic enough, or did not reflect the values of the Soviet people.

Furthermore, books were not supposed to portray religion in a positive light, or offer an un-Soviet interpretation of various historical events. Also, authors who emigrated from Soviet Russia were never published - they were considered to be state enemies and traitors to the Fatherland.

Here are some of the books that were published just before the collapse of the USSR.

Bunin lived in Moscow when the 1917 Revolution took place. He did not support the Bolshevik coup, but sympathized with the White movement and even wanted to volunteer for their army. In 1920, he emigrated to France.

In his diaries Bunin described his attitude to the Bolsheviks and his horror at the chaos and disorder that reigned in the streets during the Revolution and Civil War. On the basis of these notes he later compiled his famous Cursed Days. In Paris it was published straightaway in 1925, but in the USSR this "anti-Soviet" text simply could not see the light of day.

After the death of Stalin, some literary works by Bunin were published in the USSR in small print runs, but Cursed Days, with its scathing condemnation of the Bolsheviks and the Revolution, was banned until Perestroika, and came out only in 1988 with some amendments demanded by the censor. The full text was published only in 1990.

Read more: 6 unmissable films about the 1917 Russian Revolution

Zamyatin's dystopian sci-fi novel greatly influenced both George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. 1984 and Brave New World were written after We. None of these novels were allowed to be published in the USSR.

We describes a totalitarian state very reminiscent of War Communism in which a person's life, including his intimate life, is under the authorities' control. Soviet censors saw the novel as a lampoon on the Soviet system (and were right to do so), and perceived some of its references to the events of the Civil War as unflattering to the Bolsheviks.

They wanted to expel Zamyatin from the country together with a group of other anti-Soviet writers, but then he was arrested "until further notice". Thanks to petitions from his friends, eventually he was released.

Zamyatin managed to smuggle the manuscript to the West prior to his arrest, and the novel was published in the U.S. and later in Europe. At home, the author was subjected to persecution for this "betrayal", and in 1931 he asked Stalin for permission to leave the country. Once again, influential people came to his rescue - Stalin's favorite, Maxim Gorky, interceded on Zamyatin's behalf, and the author of We was allowed to leave the USSR. From 1931 until his death in 1937, Zamyatin lived in Paris.

We was eventually published in the USSR in 1988.

Most works of literature for which Russian readers admire Bulgakov were published after his death. During the thaw of the 1960s, The White Guard and The Master and Margarita were officially published, albeit with passages cut and appalling meddling on the part of the censor.

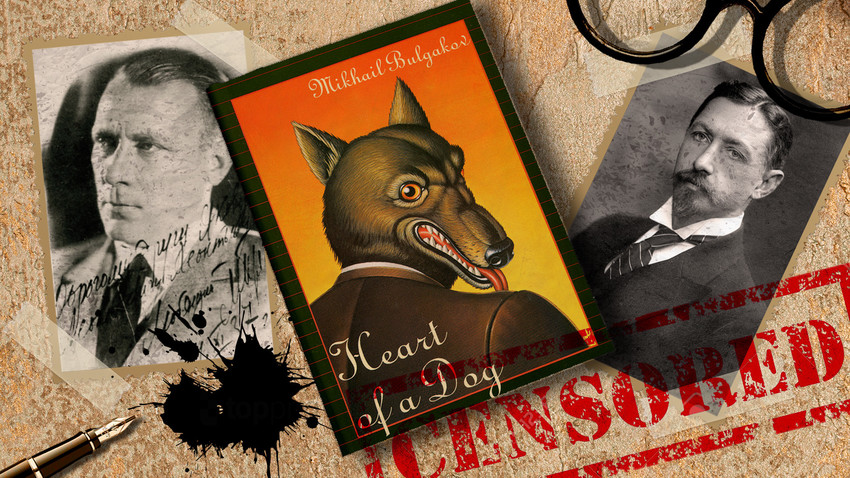

In The Heart of a Dog the author draws a clear parallel between a stray mongrel, which after surgery turns into the disgusting "prole," Sharikov, and the wretched lower social classes that seized power in the country and were terrorizing the more educated parts of society. Bulgakov was advised not to bother showing it to Glavlit, but he did, and not surprisingly the watchdog construed it as a cutting political satire unsuitable for publication.

In 1926, the manuscript was confiscated, but at the request of Maxim Gorky the author later got it back. Soon, it appeared in samizdat and became incredibly popular.

The Heart of a Dog was published in the USSR for the first time in 1987, and in 1988 a film adaptation of the book came out. The novel became a huge hit, with quotes from it entering the Russian language as popular catchphrases.

The novel, which is an impartial telling of the Revolution and Civil War in Russia, is one of the best works of 20th century Russian literature (and not just 20th century). Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Doctor Zhivago but, at the same time, the book led to his being subjected to a real hate campaign in the USSR.

After the "heavyweight" literary journals that customarily serialize all the latest works of literature refused to publish the novel, he sent it to Italy where it was finally published (recently declassified documents show the CIA's involvement in the publication of the novel in the countries of the socialist bloc). Following this, Pasternak was branded a traitor in his homeland, and his persecution began.

The editorial board of Novy Mir literary magazine claimed in an open letter that the book was a slanderous portrayal of the October Revolution "and the people who carried out the Revolution and built socialism in the Soviet Union". The Nobel Prize was described as a political stunt. In the opinion of the "genuinely Soviet" editors, the prize was the result of "anti-Soviet hype around the novel," and in no way reflected the "literary qualities of Pasternak's work".

The denunciations became so widespread that ordinary workers were dragged into it. A phrase was even coined paraphrasing an accusatory speech at a party meeting: "I haven't read Pasternak but I condemn him." In the end, Pasternak had to give up his Nobel Prize due to threats of expulsion from the country.

Doctor Zhivago was published in the USSR only in 1988 - ironically by Novy Mir.

Read more: The spy story behind the Zhivago Affair

As a war reporter, Grossman was one of the first to arrive at the Treblinka extermination camp that was liberated by Soviet soldiers. His article, The Hell of Treblinka, was the first publication about the Holocaust in the Soviet press.

For Grossman the topic was also very personal - his mother died during the mass executions of Jews in Berdichev. Together with another war reporter, Ilya Ehrenburg, Grossman compiled documentary evidence about the Holocaust, alongside his personal observations, in The Black Book.

The USSR didn't want to publish the book in order to avoid specifically highlighting the deaths of Jews. It was believed that writers should not single out any particular nationality, but rather, to write about Nazi crimes and the suffering of the Soviet people as a whole.

In 1947, the book was published in English in the U.S. The Russian-language version was first published in 1980 in Israel, but even then, not in its full version. In Russia the book’s full version came out only in 2015!

The story of this novel’s writing sounds like a blockbuster. In many ways it is based on the life of Grossman himself. In Life and Fate Grossman writes about the Battle of Stalingrad, into the vortex of which he was swept as a war reporter, about life during wartime evacuations, about the political purges, and how neighbors and friends turned away from the relatives of victims of the purges.

Grossman's epic, now described as the ‘War and Peace of the 20th Century’, was seen in the USSR as ideologically harmful because it contained too much criticism of the Stalinist regime (Grossman even compared Stalin to Hitler). Grossman was refused permission to publish the novel. Moreover, the KGB carried out a search of the author's home and confiscated the ‘dangerous’ manuscript.

Fortunately, a friend had a copy and managed to smuggle it out of the country. The novel was published in Switzerland in 1980, and then finally in 1988 in the USSR during Perestroika, but with some passages cut. The full version came out only in 1990.

In 2013, at an official ceremony, the FSB (successor to the KGB) formally presented the manuscript to the Ministry of Culture.

The story of forbidden love between a man and an underage nymphet was banned in many countries, such as France and Britain, and even in the U.S. several publishers refused to handle Lolita.

In the USSR, Nabokov could not be published at all because he was the son of a centrist politician who was vehemently opposed to the Bolsheviks. The entire Nabokov family left Russia after the Revolution and were regarded as "traitors".

Books by Nabokov, however, were circulated in samizdat, and the intellectual elite had the opportunity to read them. In the 1950s-1960s, academic literary articles began to quote individual works by Nabokov, including his commentary to Alexander Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, which Nabokov translated into English.

Nabokov himself didn't believe that Lolita would ever be published in the USSR. In his postscript to the Russian translation, which he penned in the 1960s, he wrote: "I find it difficult to imagine the regime in my homeland, whether liberal or totalitarian, under which the censorship would pass Lolita."

Still, the book was officially published but only in 1989.

Read more: 7 reasons why we adore Vladimir Nabokov

Thanks to Solzhenitsyn the Soviet press began to talk about the Gulag for the first time. Many families had been persecuted and tens of thousands of people served prison sentences on political charges. However, for many years the press kept quiet about the real conditions of prisoners, such as hunger, disease and unendurable labor.

In 1968, Solzhenitsyn's One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was, as if by a miracle, published by Novy Mir. It was based on his personal experience of eight years in prison camps.

Solzhenitsyn devoted the rest of his life to researching the USSR’s penal system and political persecutions. He collected information about camps across the country, and described how they had been set up and who worked in them. All of this was described in The Gulag Archipelago.

Solzhenitsyn was one of the most prominent Soviet dissidents, a freedom fighter and vehement opponent of censorship. The KGB kept him under close surveillance and it eventually found the manuscript of The Gulag Archipelago. By that time, however, he had already passed the text to the West, and in 1973 it was published in Paris. Solzhenitsyn was condemned as a traitor to the Motherland, stripped of his citizenship and forced to leave the country.

In 1989, individual chapters of his work appeared in Novy Mir, and in 1990 the book was published in full. Also at that time, Solzhenitsyn had his citizenship restored and he flew back to Russia.

The author describes her book as a "chronicle of the era of the cult of personality". Like many other works of literature exposing the horrors of the Stalinist regime, Ginzburg's book was first published abroad, and it came out in the USSR only in 1988.

Ginzburg was arrested during the time of the Great Terror in 1937, and spent 10 years in prison. The autobiographical novel describes beatings during interrogations and fabricated charges, and tells of people forced to confess to crimes they did not commit and how they were intimidated with threats of their whole family being arrested.

Ginzburg writes about denunciations, about neighbours snitching on neighbors to the authorities in the hope of ingratiating themselves with the NKVD [precursor of the KGB], but subsequently finding themselves in prison for not reporting enough or on the basis of further denunciations.

Particularly shocking is her depiction of a women’s prison where men wearing shoulder-straps beat up their female fellow citizens until they lose their memories and their minds.

A film based on the book, Within the Whirlwind, with Emily Watson as Eugenia Ginzburg came out in 2009. Since 1989, and until this day, the play, Journey into the Whirlwind, has been running at the Sovremennik Theater in Moscow.

The fate of many poets of the Soviet period was a sad one. The Party and Glavlit demanded patriotic verse devoted to the heroism of the Soviet people, their work and their happy life in the USSR. Lyricism, love and suffering - none of this was allowed to appear in print, and was regarded as hostile, "capitalist" and something irrelevant to the Soviet people. The emigre writers Zinaida Gippius and Dmitry Merezhkovsky did not appear in print. Only in the 1960s were selected poems by Konstantin Balmont and Marina Tsvetaeva published. The poetry of Nikolai Gumilev, who had been persecuted for political reasons, appeared in print only in 1986, and the first publication of the avant-garde poems of Vladislav Khodasevich were a big event in 1989. Many poems by Sergei Yesenin, once one of the most popular peasant poets, were not published for a long time.

Many poets were forced to write for themselves and keep their work in the drawer of their writing desk, but it was dangerous to keep certain poems even inside a writing desk. There is a story that Anna Akhmatova would write her poems on scraps of paper and give them to friends to memorize, and then burn the scraps of paper. Her friends would ask their friends to do the same, and that is how her poems were disseminated. Also, collections of poetry were actively circulated in samizdat.

Many poets were subjected to political persecution, although the charges, by and large, had nothing to do with poetry - they were suspected of involvement in anti-Soviet conspiracies. However, Osip Mandelstam paid the price for his epigram about Stalin: "We live without feeling the country beneath us" (tr. David McDufff), in which he calls the leader a "Kremlin mountaineer", hinting at his poor level of education.

The NKVD, later the KGB, confiscated manuscripts and samizdat compilations of poems, but didn't destroy anything. All the texts were stored in the archives of the security services or sent to special library repositories, access to which was available for only a restricted number of people. Thanks to these archives, many lost works of literature were restored and published after the collapse of the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox