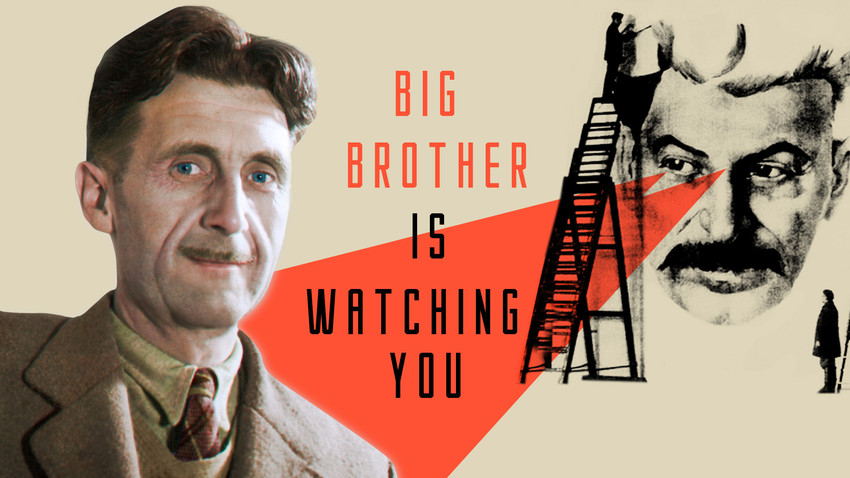

George Orwell. Nineteen Eight-Four

British LibraryGeorge Orwell (born Eric Blair) clicked with Russian readers. First, because 1984 and the “parable” Animal Farm drew clear parallels with Soviet society. And second, because his works were banned for many years inside the USSR, which meant only thing — they were worth reading.

Orwell’s books began to be printed in thesamizdat of the 1960s, and brave readers were able to get hold of a copy for one night’s reading. Vyacheslav Nedoshivin, the author of a new biography of Orwell (AST: Elena Shubina Publications, 2018), recalls how he spent such a night with colleagues from the newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda.

“I clearly remember how the door to the editorial office was locked, a pencil was surgically inserted into the telephone after removing the rotary disk (which supposedly thwarted wiretapping), and the conversation began in hushed tones. It was heart-pounding stuff, especially learning that your newspaper was just a tiny cog in the machine of the sprawling Ministry of Truth; that the ‘disconnected’ phone was not to protect against the KGB, but from Big Brother, who ‘sees’ everyone in the world; that Stalin, Khrushchev, and the ‘immortal’ Brezhnev were Napoleon and Snowball in Animal Farm, or simply power-hungry pigs (at this point my heart stopped pounding and leaped out of my chest!).”

Nedoshivin was so impressed that he wrote his dissertation on the topic of dystopia, carried out the first philological analysis of 1984 in the USSR, and co-authored a translation of Animal Farm into Russian. He believes his biography is just one of many, many more to come.

George Orwell. Animal Farm (A special edition of the book with pictures by Ralph Steadman, is published by Secker & Warburg)

Getty ImagesThere was tremendous sympathy for the Russian Revolution in Britain, and revolutionary ideas pervaded the country. Orwell recalls a school test in which he had to list ten outstanding contemporaries — he and almost the entire class named Vladimir Lenin among them.

At Eton College, where Orwell studied, it was fashionable to behave "like a Bolshevik." The future writer, like most well-read English teenagers, regarded himself as a socialist.

Naturally, the adult Orwell sympathized with the leftist movement. In 1936 he went to fight in the Spanish Civil War in the ranks of the left-wing Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). There he was wounded, but after recovering did not continue fighting, since the party had been banned as anti-Stalinist, and it was vital to keep such an ally as Stalin on the side of the International Brigades.

Later, in 1943-44, Orwell wrote his famous fairy-tale Animal Farm — a satire on the Russian Revolution and the Stalinist regime. At the time, it was considered too radical even for British censors. With the war in full swing, it seemed inappropriate to criticize a crucial ally, so it remained unpublished until 1945.

The KGB archive contains a dossier on Orwell in which he is described as “the author of the most vile book about the Soviet Union.” For many years his name was taboo in the USSR (Read more: 10 books that were banned in the USSR).

For his part, Orwell was eager to ensure that sympathy for the USSR did not spread throughout England. It is known that for many years he kept a special notebook in which he wrote down the names of people whom he suspected of having “criminal” leanings toward communism and the Stalinist regime. In 1949 he was offered a government job in counter-propaganda, but he declined, opting simply to give his list to the British Foreign Office (it was later published). The names included J.B. Priestley, Charlie Chaplin, George Bernard Shaw, and John Steinbeck — with notes on each.

According to some accounts, Orwell had long-standing links to the British intelligence services, which allegedly even paid for his novels to be printed abroad, using them as anti-Soviet propaganda.

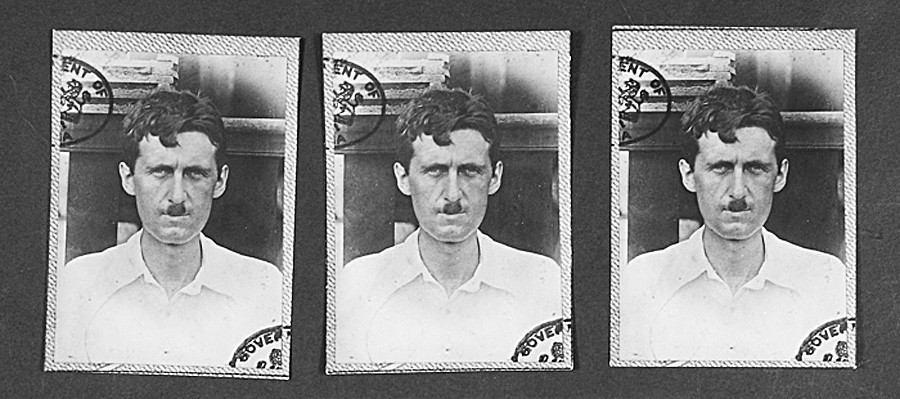

Eric Blair (George Orwell) from his Metropolitan Police file

The National Archives UK/Getty ImagesAs a young man, Orwell went to Paris in search of "writer’s inspiration." These years would later be chronicled in the autobiographical work Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). Like many writers eager to partake of “the moveable feast” (as Ernest Hemingway called Paris), Orwell was crushed by poverty. He was saved from starvation by a Russian émigré who had fled to France to escape the Bolsheviks. He found Orwell a job as a washer-upper in a restaurant, which was frequented by Russians of various stripes.

Orwell’s social circle included several of them — for example, he was acquainted with Russian émigré artist Boris Anrep, known for his mosaics (four of which decorate the floor of the entrance to London’s National Gallery) and his affair with Anna Akhmatova.

Another of Orwell’s Russian acquaintances was émigré Lydia Jackson (née Zhiburtovich), who later became a writer under the pen name Elizaveta Fen. She was a friend of Orwell’s wife, and at some point she and the British author became drawn to one another. It is not known for certain how far things went. Lydia responded warmly to his hugs and even kisses, though she may have done so purely out of sympathy.

In the 1930s-40s, despite the choking censorship, the Soviet magazine International Literature still managed to print excerpts and reviews of Western novels (even Joyce’s Ulysses, which was banned as “immoral” in many countries, including England). Editor-in-chief Sergei Dinamov is known to have written a letter to Orwell in 1937 asking him to send a copy of the latter’s book The Road to Wigan Pier, which he found interesting and wanted to review.

A few months later he received a response. Orwell apologized for not writing sooner — he had just returned from Spain. He also wrote that he had reconsidered some of the views expressed in the book. Enclosing a copy as requested, he nevertheless warned the editor-in-chief that he had fought in Spain on the side of the POUM, which was now regarded as anti-Soviet: “I tell you this because it may be that your paper would not care to have contributions from a POUM member, and I do not wish to introduce myself to you under false pretences.”

The editor-in-chief was required to hand the letter over to the NKVD, and reply to Orwell that he was grateful for the latter’s sincerity, but was forced to break off their relationship.

A portrait of Yevgeny Zamyatin by famous Russian artist Boris Kustodiev

Public domainPenned in 1920, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We was immediately banned in the USSR and first published in the West only in 1927. Orwell read it much later, writing a review of it in 1946.

He describesWeas “certainly an unusual [book], and it is astonishing that no English publisher has been enterprising enough to reissue it.” Orwell was greatly impressed that Zamyatin had written the book before the horrors of Stalinism, noting that “he cannot have had the Stalin dictatorship in mind, and conditions in Russia in 1923 were not such that anyone would revolt against them on the ground that life was becoming too safe and comfortable. What Zamyatin seems to be aiming at is not any particular country but the implied aims of industrial civilization.”

Orwell also drew in-depth parallels between Zamyatin’s novel and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, exposing the source of much of Huxley’s nightmare vision. Orwell acknowledged his own literary debt to Zamyatin, and numerous scholars have since highlighted the similarities between the two.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox