Tolstoy was a unique and controversial character. In the story of his life, dozens of love affairs and romantic entanglements sit side by side with sermons on morality, chastity and family values. Was he perhaps using moral preaching in his works to atone for his own sins?

“When my brothers took me to a brothel for the first time and I committed the act, I then stood by the woman's bed and wept,” Tolstoy wrote about his loss of virginity. He was 16.

For the first time Tolstoy experienced romantic and carnal feelings for a woman when he was about 13. He wrote in his diary: “One strong feeling, like love, I experienced only when I was 13 or 14 years old. But I [don't] want to believe that it was love because its object was a fat maid (albeit with a very pretty face). Besides, the period between 13 and 15 years of age is the most confused time for a boy (adolescence): you don’t know what to apply yourself to, and lust hits you with extraordinary force.”

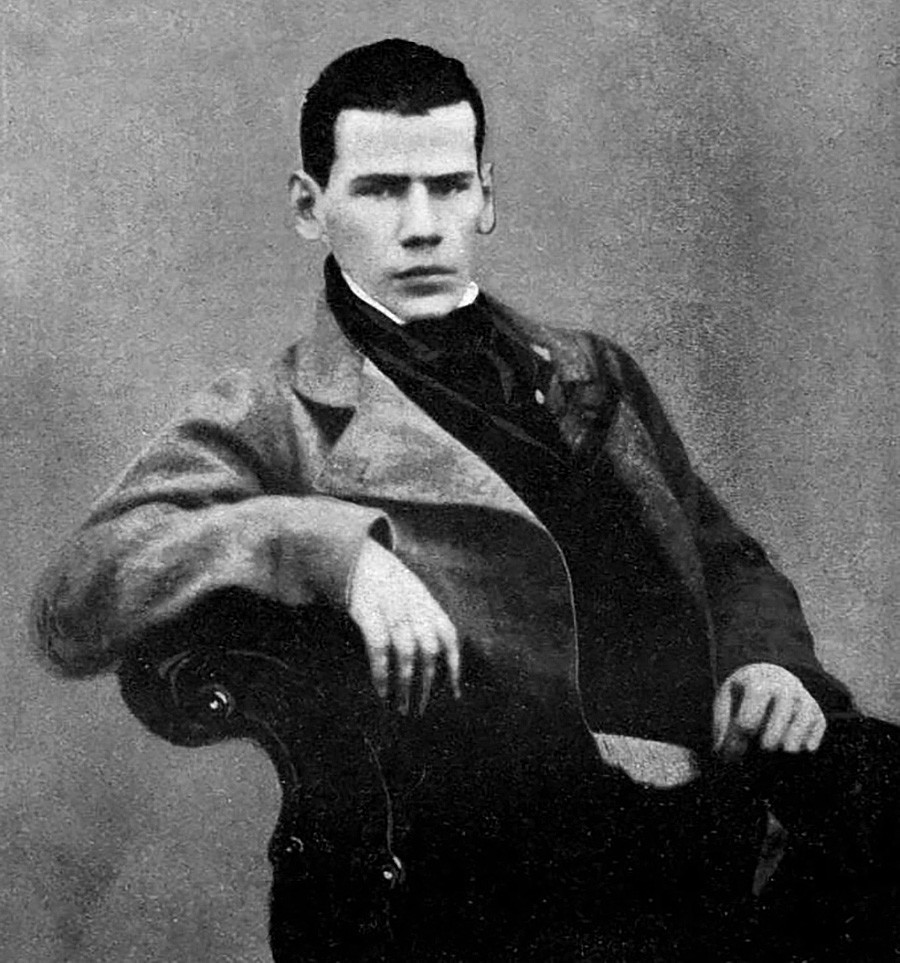

Leo Tolstoy in 1848 (aged 20)

Public domainAt 18, the future writer began to keep a diary: he was in the hospital, receiving treatment for a sexually transmitted disease. This affliction came as a real shock, and he needed to sort out his feelings. However, even the illness did not stop the young Tolstoy from seeking more carnal pleasures: he often wrote about sensuality and reflected on his own lust.

In 1854, during the Crimean War, Tolstoy's military unit spent some time in Bucharest. With obvious disappointment, the 26-year-old writer once again noted in his diary how he “had gone bad”: “I had several women, I lied, I was vain, and, worst of all, I did not behave under fire as I had hoped I would."

A couple of years later, he came to his estate, Yasnaya Polyana, and, suffering from idleness, complained that every day he experienced lustful desires and felt terribly sordid as a result. “I have decided somewhere and somehow to get a mistress for these two months,” “Terrible lust, reaching the point of physical illness,” “I was wandering in the garden. A very pretty peasant woman, of very pleasing beauty. I am unbearably disgusted with these helpless impulses at vice. Vice itself would have been better."

Judging by the writer’s diaries, it may seem that Tolstoy was an unthinkable womanizer, and many researchers come to this conclusion, spreading rumors about a huge number of children supposedly conceived by Tolstoy with peasant women (in fact, only one such child is known). And yet, dissipation and visits to brothels were commonplace for a young aristocrat of that era. It is the way Tolstoy endlessly reproached himself for this, the amount of attention he paid to this, and the concern he felt that made him stand out.

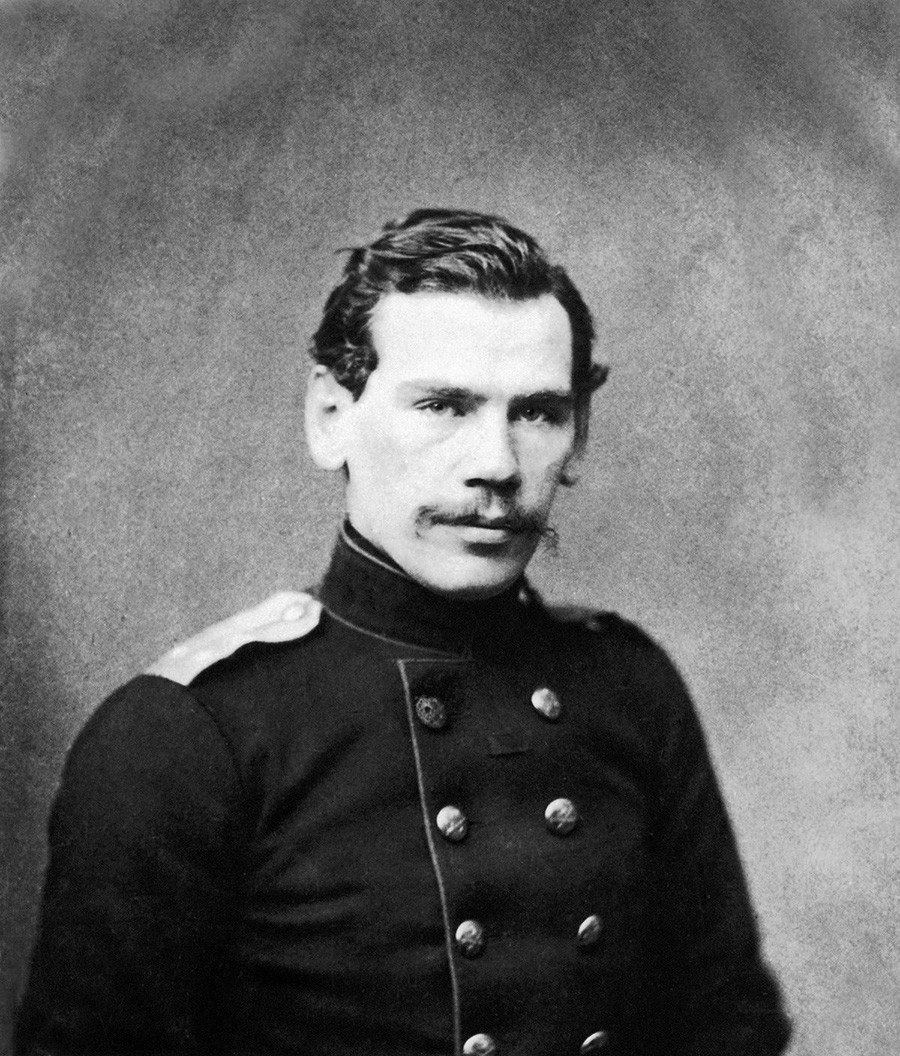

Leo Tolstoy in 1856

Public domainThe writer constantly reconsidered his attitude to carnal love and set himself a goal of what kind of person he should become. Thus, in 1855, he wrote: “A human being generally strives for spiritual life, and to achieve spiritual goals one needs a position in which the satisfaction of one's carnal desires is not counter to or is aligned with the satisfaction of one's spiritual aspirations <...> So, here is my new rule in addition to those that I set myself long ago - to be active, reasonable and modest.”

To stifle his lust, Tolstoy decided to constantly keep himself busy. Starting in 1856, he vigorously searched for a wife and was determined to put an end to his debauched lifestyle. Yet, none of the young ladies that he met proved to be a match. Only six years later, when he turned 34, Tolstoy met 18-year-old Sophia Bers, who “suited him”.

Before the wedding, he tried to "clear his conscience" and showed his fiancé his diaries: he wanted no secrets between them and swore he would be faithful to her. The amorous affairs described in his writings brought Sophia to tears. However, she agreed to go ahead with the wedding, and after the ceremony Tolstoy immediately took his young wife to Yasnaya Polyana.

Sophia Bers in 1862

Archive photoTolstoy was not only moral but also very devout. He is believed to have been a tyrant at home, forcing his wife to have 13 children, giving one birth after another for the simple reason that he was “afraid of calling down the wrath of God”.

Once, when Sophia had a malignant tumor, a doctor was called and he asked her husband’s permission for surgery. But Tolstoy could not bring himself to make a decision for a long time, believing that “one cannot resist the will of God”, even if his wife might die.

Nevertheless, his wife loved him and was completely devoted: she conducted his affairs (and the affairs of the whole Yasnaya Polyana), raised the children and did the household chores, as well as copied War and Peace by hand several times.

Tolstoy believed that a woman's destiny was at home and in family life, such as, for example, Natasha Rostova in War and Peace, who found happiness in her children, or Kitty Shcherbatskaya in Anna Karenina, who was transformed by motherhood. Everyone remembers what Tolstoy did to Karenina, who had sacrificed her family for the sake of passion, forgetting about her son.

In the 1880s, Tolstoy experienced a spiritual revolution and completely changed his view of the world. For example, he wanted to renounce private property and copyright to his works. His attitude to marriage also changed. If previously his works presented family as the highest value, now he was absolutely disappointed in marriage, and such thoughts were reflected in The Kreutzer Sonata.

In the novella, he speaks about the base nature of passion, about a human being's inability to control one's lust, and about the destructive power of jealousy. The protagonist, who in his youth was as much a libertine as the author himself, says that women are created only to excite men. Out of jealousy, he kills his innocent wife.

At the time, Tolstoy was not just a famous writer but a real spiritual leader. Each of his new works was devoured by the public and had an enormous impact. That is why after its release The Kreutzer Sonata was banned by the tsar's censors. Tolstoy scholar Pavel Basinsky writes: “Having read The Kreutzer Sonata, young people renounced matrimony and procreation, arguing that family life was based on an unchaste sexual instinct.”

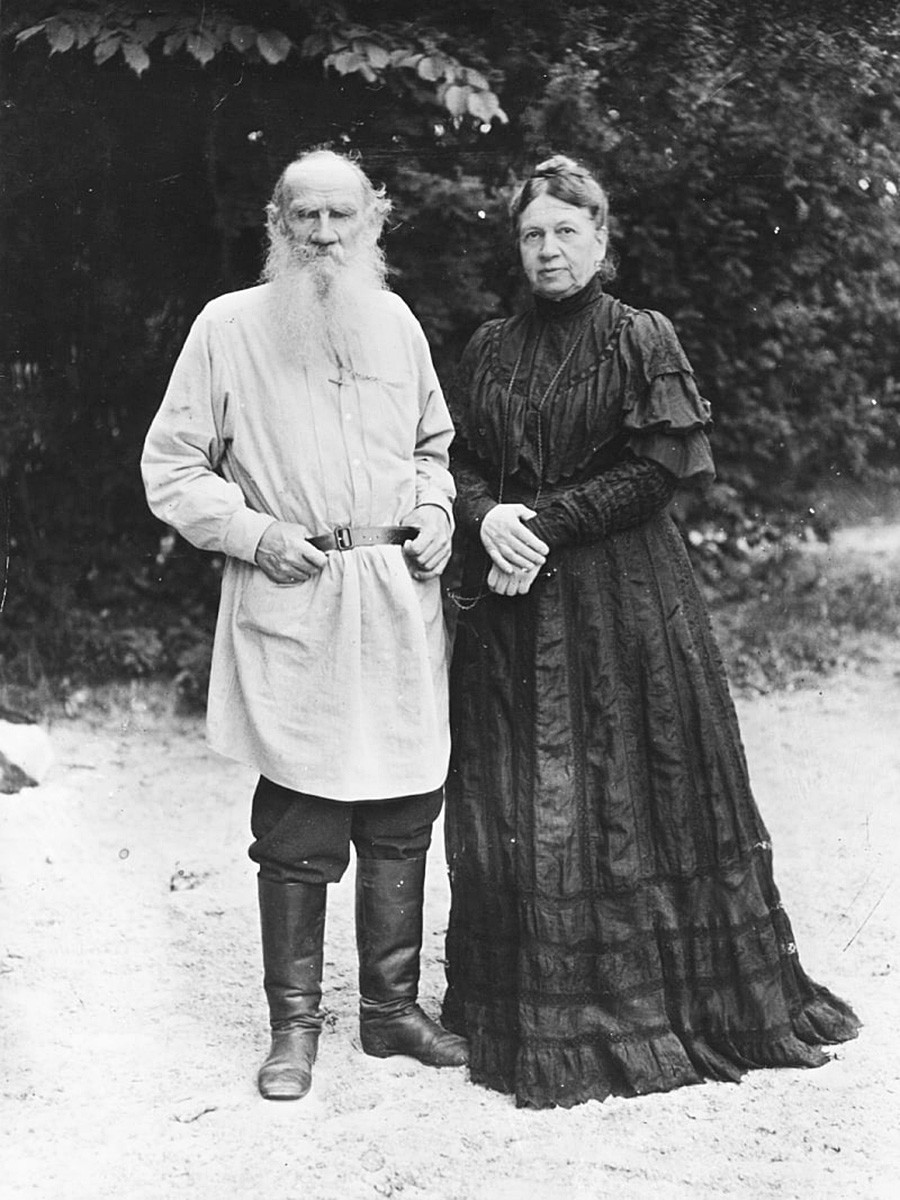

Leo Tolstoy and his wife ca. 1906

Archive photoThe writer now perceived sex not as a joy of youth, but as a serious addiction. “A fornicator is not a term of abuse but a condition (I think the same applies to a fornicatress), a state of anxiety, curiosity and the need for novelty deriving from pleasurable interaction not with one, but with many. Like a drunkard, he can abstain, but a drunkard is a drunkard and a fornicator is a fornicator and at the first loss of guard he will fall,” Tolstoy wrote in a diary. “I am a fornicator,” he continued.

While working on The Kreutzer Sonata, Tolstoy received brochures from the Shakers, an American religious movement that preached celibacy. He wrote to his friend Vladimir Chertkov that they had only strengthened his view of marriage. Now, he preached not only morality and the fight against fornication, but chastity and celibacy.

At the end of his life, Tolstoy decided to free himself from marriage altogether: he left his wife and his home. Ten days later, he suddenly died in a railway station in a neighboring region.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox