The first time when Soviet media raised the topic of Soviet labor camps for public discussion was in 1962 when the magazine Novy Mir published Alexander Solzhenitsyin’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. After that followed dozens of memoirs, as well as fiction and nonfiction books about the terrifying life of the prisoners, including Solzhenitsyn’s massive work The Gulag Archipelago, and a talented short stories selection by Varlam Shalamov called Kolyma Tales. (Read more: 5 important books about Gulag and Stalin’s Great Terror).

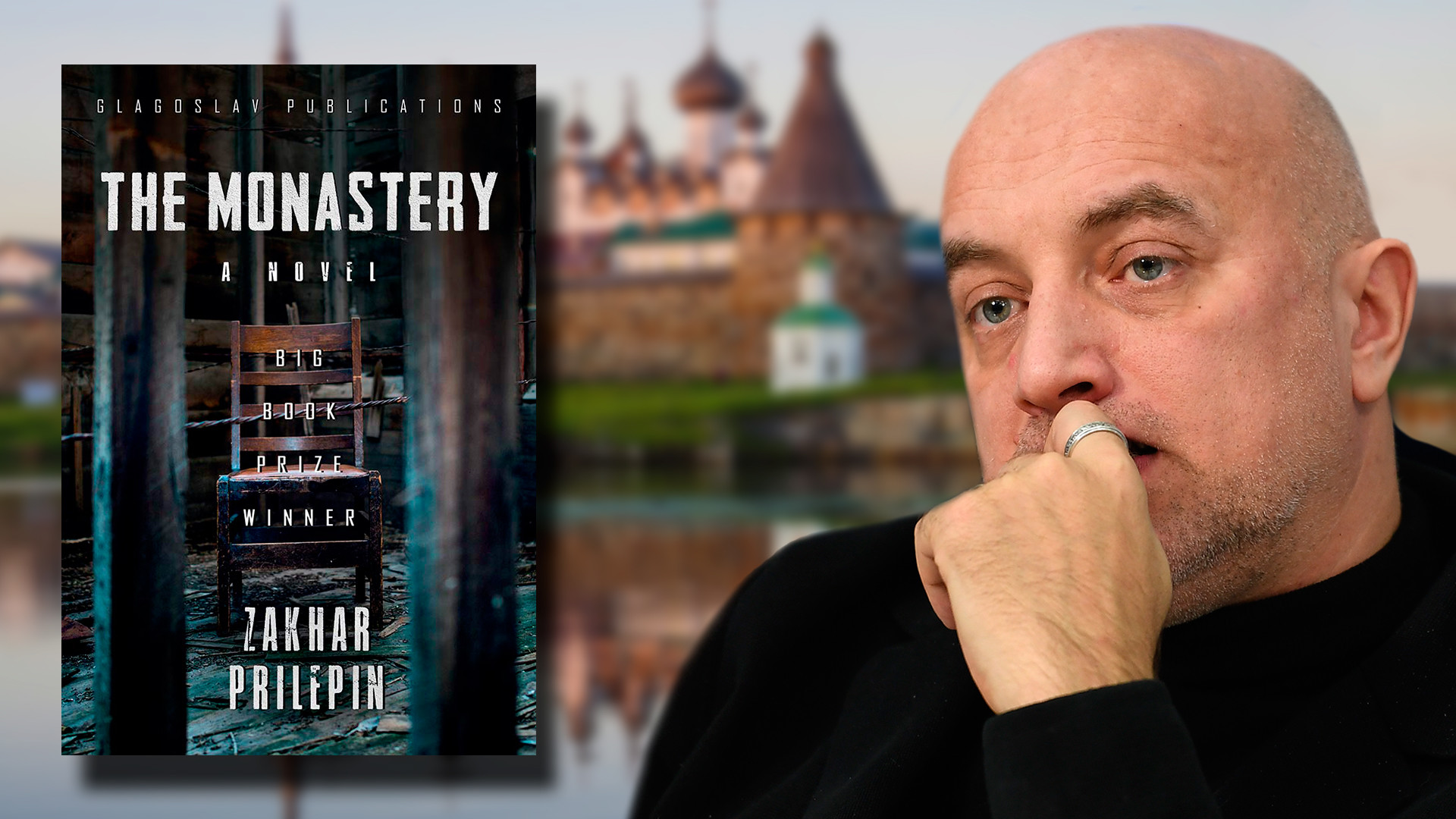

Zakhar Prilepin. The Monastery. Translated by Nicholas Kotar

Glagoslav Publications, 2020After some decades of printing all these sad and tragic books, Soviet publishers ceased, and reader interest declined because digesting such awful matters is not easy. So, Prilepin’s The Monastery is one of the first books in modern Russia that once again delves into the Gulag.

The Solovetsky monastery, 1933

Mikhail Prishvin/State Literary MuseumThe Monastery takes place in the late 1920s on the Solovetsky Islands (Solovki) in the White Sea in the north of Russia. These are the years just before Stalin’s Great Terror, when it still wasn’t that repressive. Solovki used to house an ancient monastery that always was used as a place for exile in tsarist times. In the 1920s, however, it became a labor camp for those who didn’t support the new Soviet regime, as well as for ordinary criminals, with the latter making the life of political prisoners even worse. The monastery’s religious cells were turned into dismal prison cells; and plank beds were installed inside the churches.

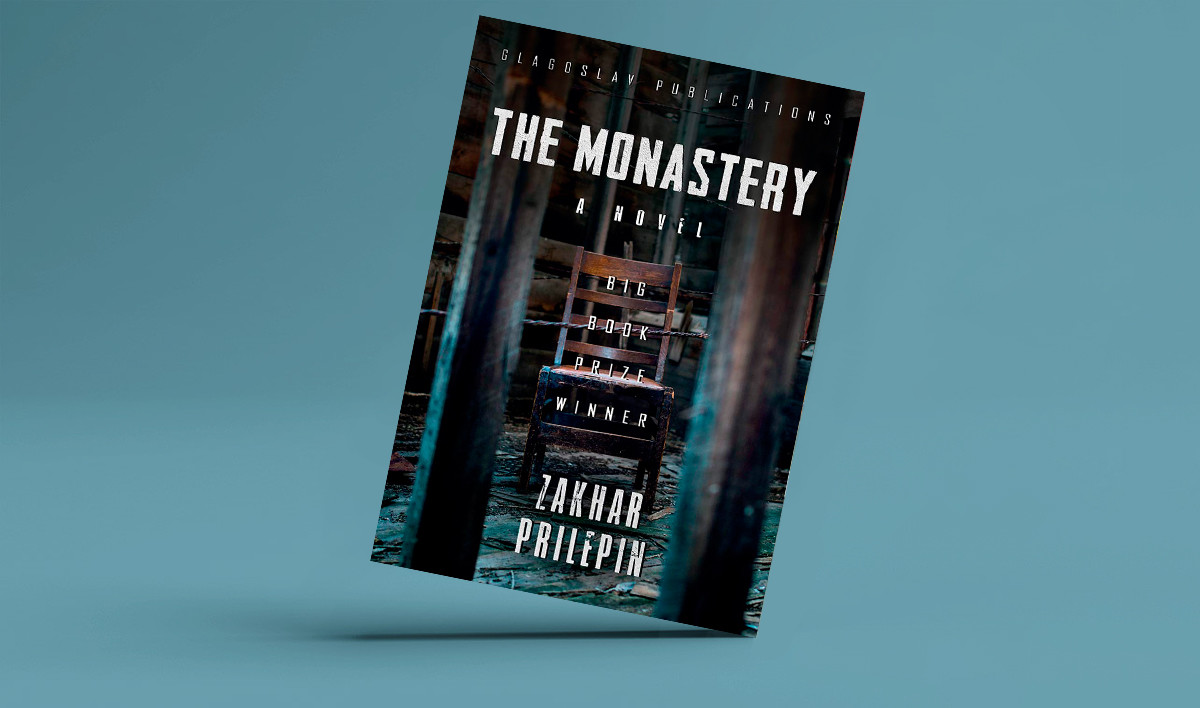

Illustration for 'The Monastery' new Russian edition by Klim Li

Elena Shubina Publications (AST), 2020Artem is a 27-year old prisoner at Solovki. He is trying to survive, and seeks a better life as far as that’s possible in the camp’s brutal conditions. He is constantly in conflict with the criminal prisoners who beat him often. Finally, he finds a clever way to make his days easier - a love affair with a female officer. With her help he is transferred to another wing, one which has ‘prestigious’ labor positions, such as a guard at the animal nursery. Even here, however, he has to always be careful and keep his eyes open.

Prisoners of Solovetsky labor camp mining clay for a brick factory

Public DomainTo write the book Prilepin spent several months on the Solovetsky Islands, investigating the archives and researching its library. While this novel is not a compilation of memoirs, it’s inspired archival documents. All the main characters are based on real-life people. The camp's commandant, Teodors Eihmanis, truly lived (his real surname was Eihmans); he was a leading figure carrying out Stalin's terror and then found himself caught in its meat grinder, and was executed in 1938.

The Solovetsky monastery nowadays

Legion MediaThe main character’s lover, Galina, was also a real person, as well as a former lover of Eihmans. Her diary is quoted at the end of the book. Another commandant, Nogtev, is also based on the true story of a very cruel and ruthless man with sadistic tendencies and who mocked the prisoners, which is also vividly described in the book.

The Solovetsky labor camp in 1933

Mikhail Prishvin/State Literary MuseumOne of the main problems of Russian literature in the 1990s and early 2000s was a lack of excellent thick novels. The critics were unsuccessfully looking for a new Tolstoy, but those new books with a focus on the modern age were not powerful enough or not overwhelming enough (a Russian reader is a spoilt brat who expects a novel to have a startling plot served in an extraordinary manner, human drama, intense philosophical discussion, and all marked by a yearning to comprehend human existence).

A still from 'The Monastery' series based on Prilepin's book (to be premiered in 2020)

Alexander Veledinsky/Valery Todorovsky Producer CompanyIn 2014 when Prilepin published his 752-page novel containing all those essential elements - strong historical setting, human drama, intriguing plot and more from that list, it earned tremendous reader interest in Russia. In addition, it received one of the most prestigious literary awards - the Big Book. Interestingly, The Monastery led a series of novels dedicated to the Gulag written by the most talented Russian authors: Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina, and The Aviator by Eugene Vodolazkin. Each of these authors worked separately, without knowing about each other’s writing; but each wrote things that certainly found a strong demand among readers who were newly interested in the topic, and who had already thoroughly read Solzhenitsyn’s books.

Zakhar Prilepin fighting in Donbass

Semyon Pegov/zaharprilepin.ruWhen The Monastery was published in Russia in 2014, Zakhar Prilepin was already a famous writer. His prose contained mostly brutal scenes that were based on his real-life experience. He wrote a short stories collection about his military service in Chechnya as a riot policeman (The Pathologies). He described life in the Russian provinces and the everyday life of an ordinary boy from a village (Sin). And one of his most famous works was the novel, Sankya, about a young and rowdy oppositioner from the banned National Bolshevik Party who actively took part in protests and was under the influence of his master (in real life, Eduard Limonov).

Prilepin’s books have always been bestsellers and won literary prizes. He is a very talented writer, and he utilizes many unusual and vivid metaphors; his narrative has a dashing pace and tone.

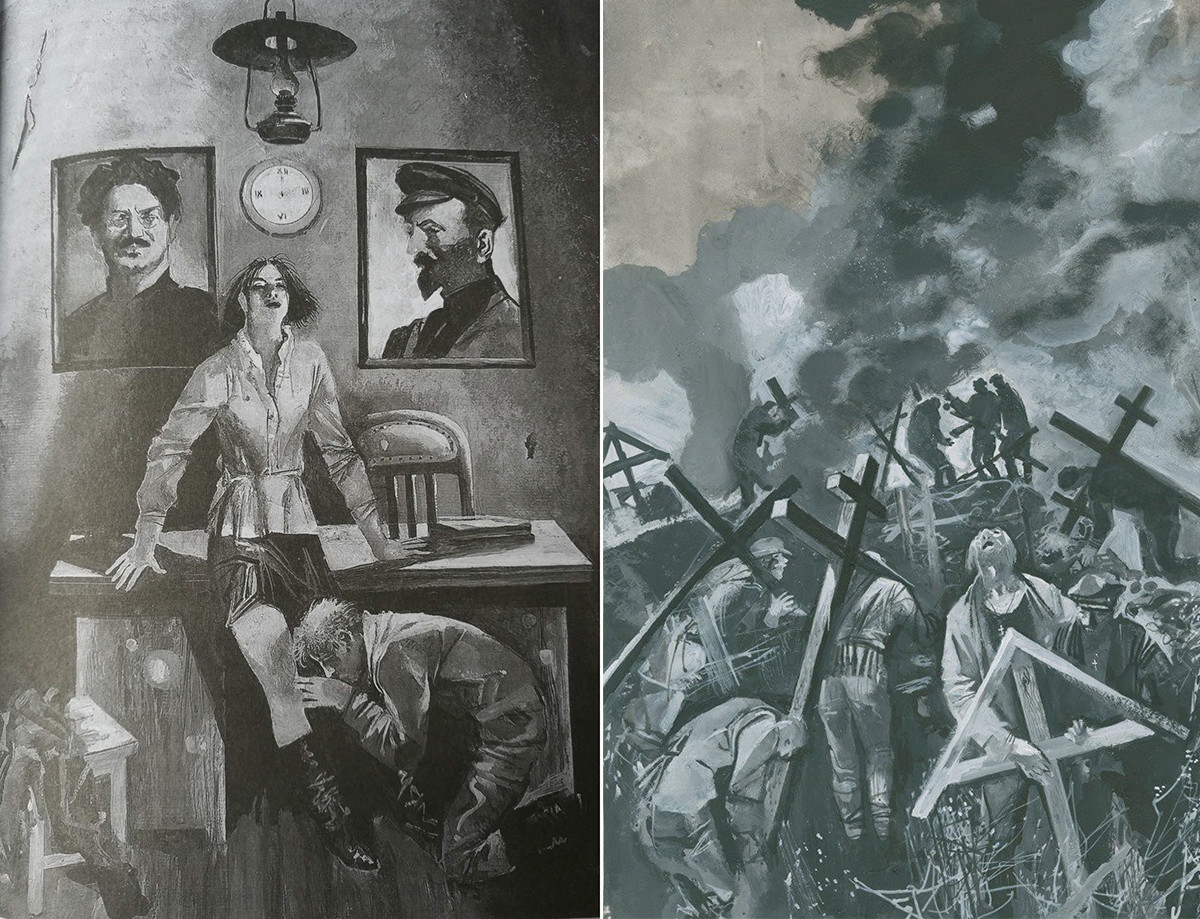

The Russian book cover of the book - Обитель

Elena Shubina Publications (AST), 2020After The Monastery was published, Prilepin went to Donetsk and even took charge of a battalion in the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) that was fighting off assaults by the Ukrainian army - this most likely was the reason why his books almost ceased being translated into English, and why his German literary agency even ended collaboration.

In 2018, when the DNR’s leader, Alexander Zakharchenko, was killed, Prilepin returned to Russia and now continues writing, working as a TV host and is involved in politics. But his time in Donbass made quite a controversy in the media - it split his Russian fans into those who can’t stand reading him any longer because of his political activity, and those who separate the man and his writing. So, now you also have to choose which side you will take.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox