Who would grasp Russia with the mind?

For her no yardstick was created:

Her soul is of a special kind,

By faith alone appreciated.

This short poem, which Tyutchev penned in 1866, is one that every Russian knows by heart. It is hard to imagine a more comprehensive and clear definition of the essence of Russia or a more accurate key to the mysterious Russian soul. There is a widely held opinion that Russia does not belong either to Europe or Asia and that it has its own path.

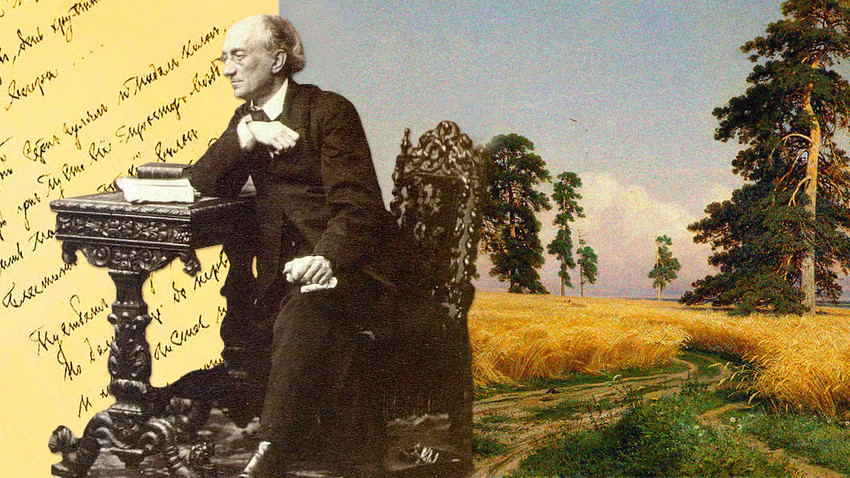

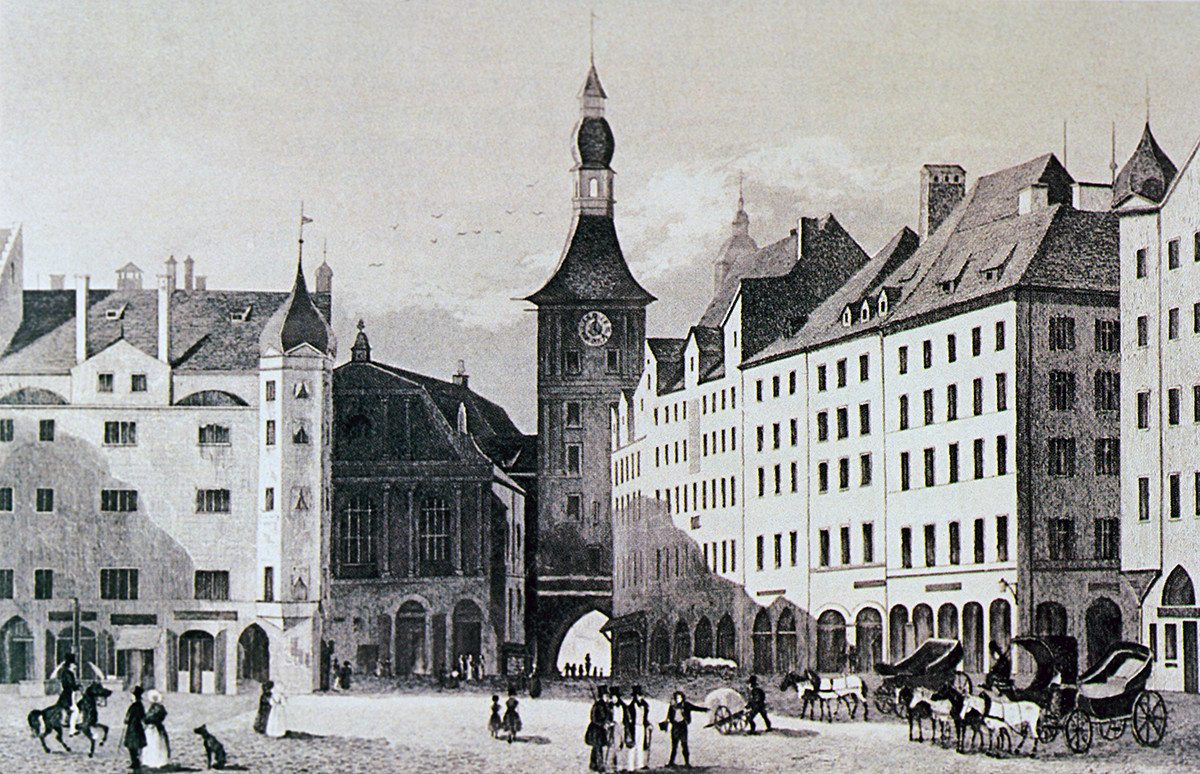

Munich, 1840. From the collection of Tyutchev's Museum-Reserve "Muranovo"

SputnikTyutchev belonged to an old aristocratic family and was born at his family estate of Ovstug in the Bryansk Region. He received an excellent education at home, knew Ancient Greek, Latin and several modern European languages. As a young man, he already translated odes by Horace.

After university, Tyutchev joined the diplomatic service and was sent on a posting to Munich. There he became friends with Heinrich Heine and was the first to translate the German poet's works into Russian. He also translated poems by Goethe and Schiller, as well as by Byron and Hugo. Many of Tyutchev's translations are still recognized as canonical by Russian philologists.

Heinrich Heine

Getty ImagesIn Germany, the poet was known as something of a ladies' man. It was there that he married a local woman, Eleanor Peterson, who bore him three daughters. All of them later became ladies-in-waiting to the Russian imperial family. Incidentally, some of Tyutchev's most famous poems "I love a thunderstorm in early May," and "Winter’s spite is vain...", which many Russians lovingly quote looking out of their windows, were in fact written in Germany and inspired by the local nature and climate.

Ippolita von Rechberg. Portrait of Fyodor Tyutchev, 1838

Tyutchev's Museum-Reserve "Muranovo"The style of Tyutchev's early poems was not unlike that of the complex archaic poetry of the 18th century. In form, those poems were similar to odes, in which he addressed an interlocutor, appealing to something. In 1820, Tyutchev developed his own theory about the purpose of poetry. He expressed it in a poem that he wrote in response to the ode, "Liberty," by Alexander Pushkin, for which the latter had been sent into exile. According to Tyutchev, the purpose of poetry lay not in criticizing the tsar or denouncing vices:

With your magical chord,

Soften hearts instead of troubling them!

Starting in the 1830s, Tyutchev's poetry began to resemble that of the Romantics: he was clearly under the influence of German poets. His poems were often short and precise, each addressing a specific topic.

One of his favorite subjects was a human being's dialogue with the universe. Personas in his poems often found themselves alone with the sky and the stars, and realized their own insignificance in comparison with eternity.

There are many small and nameless

Constellations in the sky above,

To our weak and misty eyes,

They are out of reach…

However, in his later years, Tyutchev's rhetoric underwent a complete transformation. After an almost 10-year break from poetry, he began writing again in the 1850s, this time mostly political verses. Tyutchev contemplated Russia's fate, responded to attacks from the West and extolled his homeland's lonely opposition against the rest of the world. The poem, "Who would grasp Russia with the mind?", belonged to that period.

Stepan Aleksandrovsky. Portrait of Fyodor Tyutchev, 1876

Tretyakov GalleryTyutchev returned to Russia in 1844 and continued to serve in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, overseeing its censorship division. During this time, he wrote many essays and opinion pieces, including in foreign languages. He analyzed Russia's relations with the West and expressed the idea that the Slavic peoples should unite, with Russia at their head.

Tyutchev wrote a report, "On Censorship in Russia," addressing it to the minister of foreign affairs, Prince Alexander Gorchakov (who was a fellow student of Pushkin's at the famous Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum). Concerned about the unrest in Europe, Tyutchev believed that the press should be handled with care, that it can be used to express the position of the state. At the same time, he did not advocate indiscriminate restrictions, instead urging the state to act as a parent educating the minds of immature adolescents.

"Censorship alone, no matter how it works, is unable to meet the requirements of the current state of affairs. Censorship serves as a restriction, not as a guide. Whereas in literature, as in everywhere else here, we should be thinking not of suppression but of guidance."

Emperor Nicholas I personally authorized Tyutchev to appear in the Western press, supporting Russia's positive image in the West.

Isaac Levitan. Over Eternal Quiet

Tretyakov GalleryShocked by the European revolutions of 1848-49, Tyutchev wrote a treatise, “Russia and the Revolution,” where he described the sorry state that France, Germany, and Austria found themselves in after uprisings and revolutions. He also reflected on the nature of the Russian people, concluding that revolution was alien to them.

“First of all, Russia is a Christian state, and the Russian people are a Christian nation not only because of their Orthodox faith, but also because of something even more heart-felt.” The poet argued that readiness for self-sacrifice was in Russians' blood. Whereas a revolution was contrary to Christianity and moral norms, and therefore presented no risks for Russians.

Tyutchev considered tsarist autocracy to be the path drawn for Russia by God. The poet died in 1873, so he did not live to see either the 1881 assassination of Emperor Alexander II by revolutionary terrorists or the first Russian revolution of the 20th century.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox