“You can’t give the public a genuine picture of war by viewing the battlefield through binoculars from a safe distance; you need to feel it, do it, participate in the attacks, assaults, victories, defeats, experience hunger, cold, illness, injury… you mustn’t be afraid to sacrifice your own blood, your own flesh, otherwise the painting just won’t be right,” was Russian war artist Vasily Vereshchagin’s philosophy, which he strictly adhered to at all times.

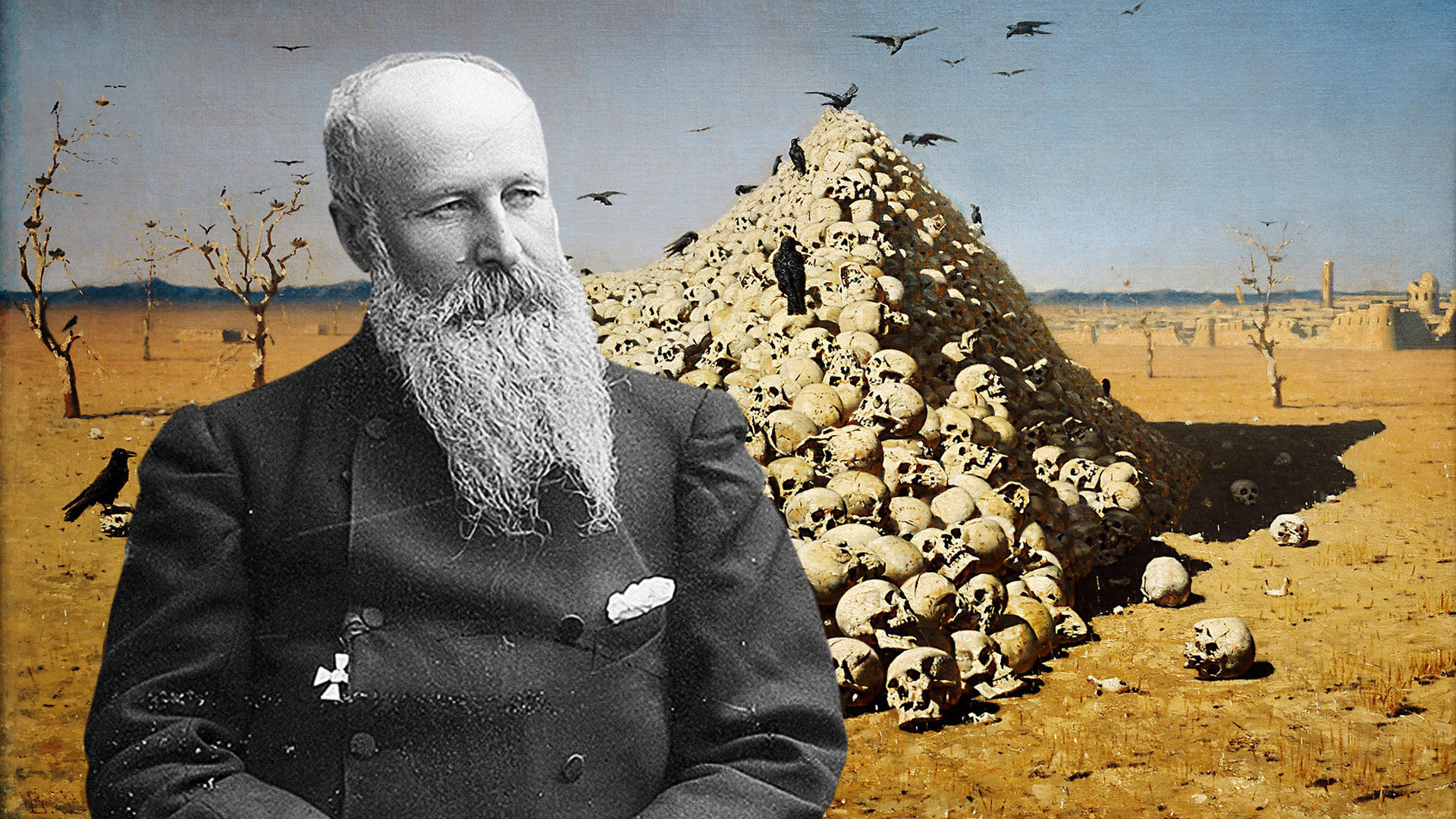

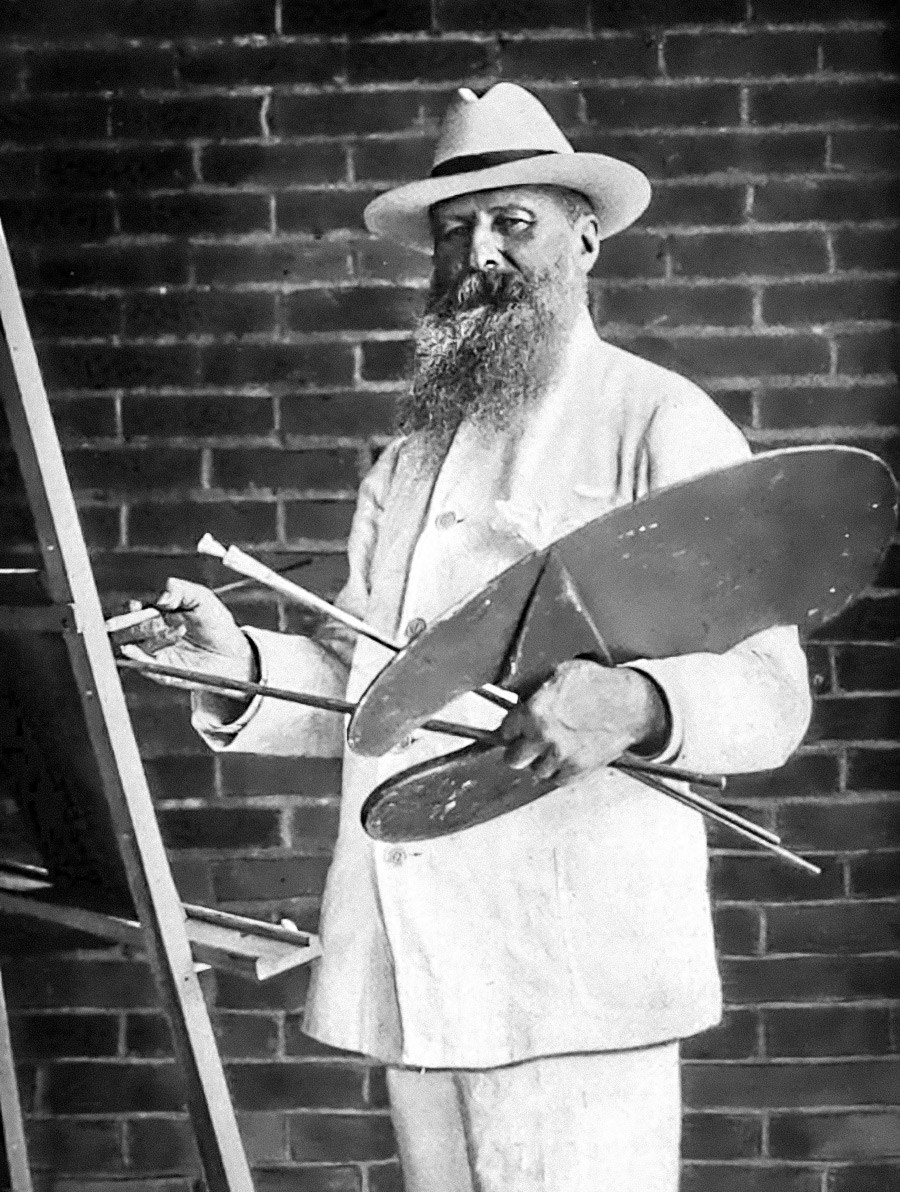

Vasily Vereshchagin in 1902.

Archive photoInstead of a war artist, Vereshchagin might just as easily have made it as a seascape painter. In 1860, at the insistence of his parents, he graduated from the Naval Cadet Corps. However, his soul was not wedded to the sea. So, after studying at the finest art academies in St Petersburg and Paris, and bearing the rank of warrant officer, he departed for Central Asia (then known as Turkestan) to serve as an artist for the local governor.

Winners, 1878-1879.

Legion MediaThe accession of Turkestan to the Russian Empire in the latter half of the 19th century was not an entirely peaceful process. In 1868, Vereshchagin was compelled to take part in the defense of Samarkand, which pitted more than 60,000 enemy troops against a Russian garrison of just 600 soldiers. For his bravery, Vereshchagin was awarded the Order of St George (4th Class).

At the Fortress Walls. Let them Enter, 1871.

Legion MediaInspired by his trips to Central Asia, Vereshchagin created a Turkestan-themed series of paintings that clearly depicted the traditions and ways of life of a culture far removed from Russia and Europe. But whereas his portraits of colorful characters and exotic types were greeted with enthusiasm by the public, his war paintings became a source of deep controversy.

Eaters of Opium, 1868.

The Museum of Arts of UzbekistanInitially, Vereshchagin imagined war as “a kind of parade, with music, fluttering banners, roaring cannons, and galloping steeds.” However, faced with the horrors of reality, he quickly saw that war is about death, suffering, physical and mental anguish, fear, cruelty, and barbarism. That is what he showed in his paintings: dying soldiers, mountains of corpses, severed heads, haggard faces.

After Good Luck (Victors), 1868.

Legion MediaMany viewers, accustomed to works glorifying the might of the invincible Russian army, reacted with hostility, accusing the artist of unpatriotic feelings. “His perpetual tendentiousness offends national pride and causes one to conclude that Vereshchagin is either a beast or a lunatic,” commented the heir to the throne, the future Alexander III, visiting an exhibition.

Mortally Wounded, 1873.

Legion MediaOne of the artist’s most striking works, characterizing his attitude to military conflict, is The Apotheosis of War, which depicts a pyramid of skulls. Originally conceived by Vereshchagin as “The Triumph of Tamerlane,” he later decided not to link it to a specific era, dedicating it to “all great conquerors — past, present, and future.”

The Apotheosis of War, 1871.

Legion Media“In my observations of life whilst journeying through the world, I was particularly struck by the fact that people today still kill each other under all sorts of pretexts and in all sorts of ways... it happens even in Christian countries in the name of the one who taught peace and love,” said Vereshchagin.

Suppression of the Indian Revolt by the English, 1884.

Public DomainAfter the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, in which Vereshchagin was seriously injured and lost his younger brother, he produced his Balkan series of paintings. Like his other military works, they are devoid of jingoism and bravado, truly and realistically conveying the full horror of the carnage.

Shipka-Sheinovo. Skobelev at Shipka, 1878-1879.

Legion Media“In front of me, as an artist, lies war. I strike it with all the strength left to me. Whether my blows have any impact is another matter, it’s a question of my talent. But I strike with force and without mercy,” Vereshchagin wrote to philanthropist Pavel Tretyakov.

Defeated. Requiem, 1879.

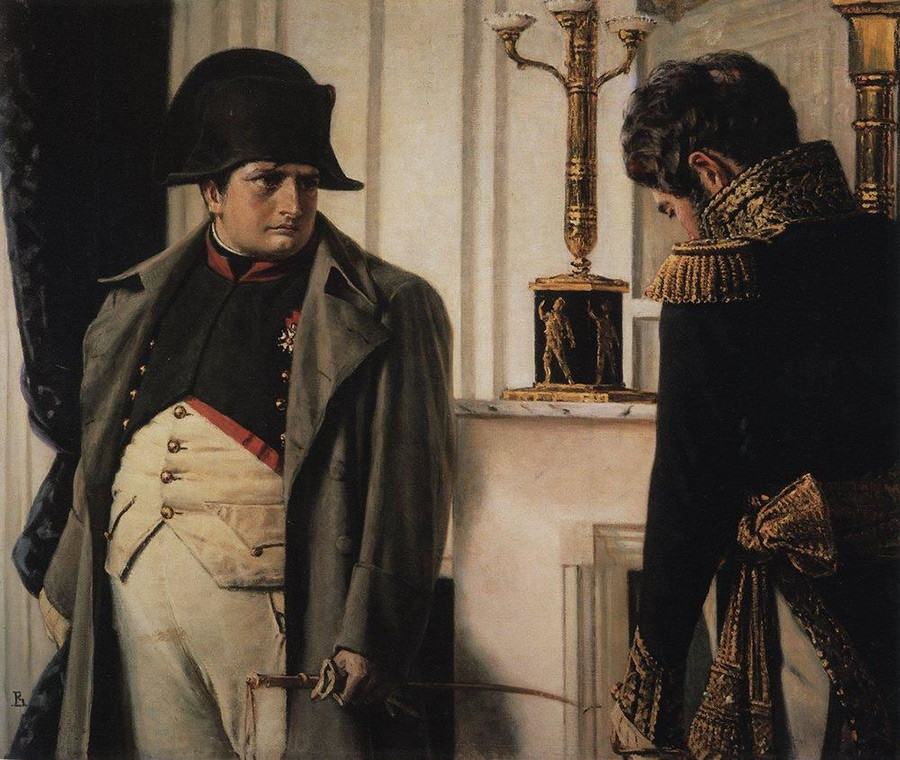

Legion MediaA separate series of works Vereshchagin devoted to the Patriotic War of 1812. The protagonist of most of these paintings is Napoleon — but not the majestic, invincible emperor as was usually portrayed, but a dazed, dispirited man, dumbfounded by the unexpectedly strong resistance of the Russians. As for Tsar Alexander I and his commanders, the artist did not depict them at all, preferring the figures of Russian soldiers and simple peasants who heeded the call to defend their land against the French.

Napoleon and Marshal Lauriston (“Peace At All Costs!”), 1900.

The State Historical MuseumThere were periods in Vereshchagin’s life and work when he grew tired of military themes. “I take what I paint too much to heart; I literally cry with grief at every person killed or wounded,” he wrote in 1882 to critic Vladimir Stasov. Often, he and his wife would go on long trips around the world, including India, Japan, and the Middle East, which resulted in various series of paintings dedicated to the peaceful life, culture, and nature of these places.

The Head of an Indian Man, 1874-1876.

The Odessa Fine Arts MuseumThe Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 was the last battleground in the life of Vasily Vasilyevich. But fate did not grant him an opportunity to capture a single episode of the conflict. At the very start of the hostilities, on April 13, 1904, he perished along with the battleship Petropavlovsk, which was blown up by a mine off the coast of China.

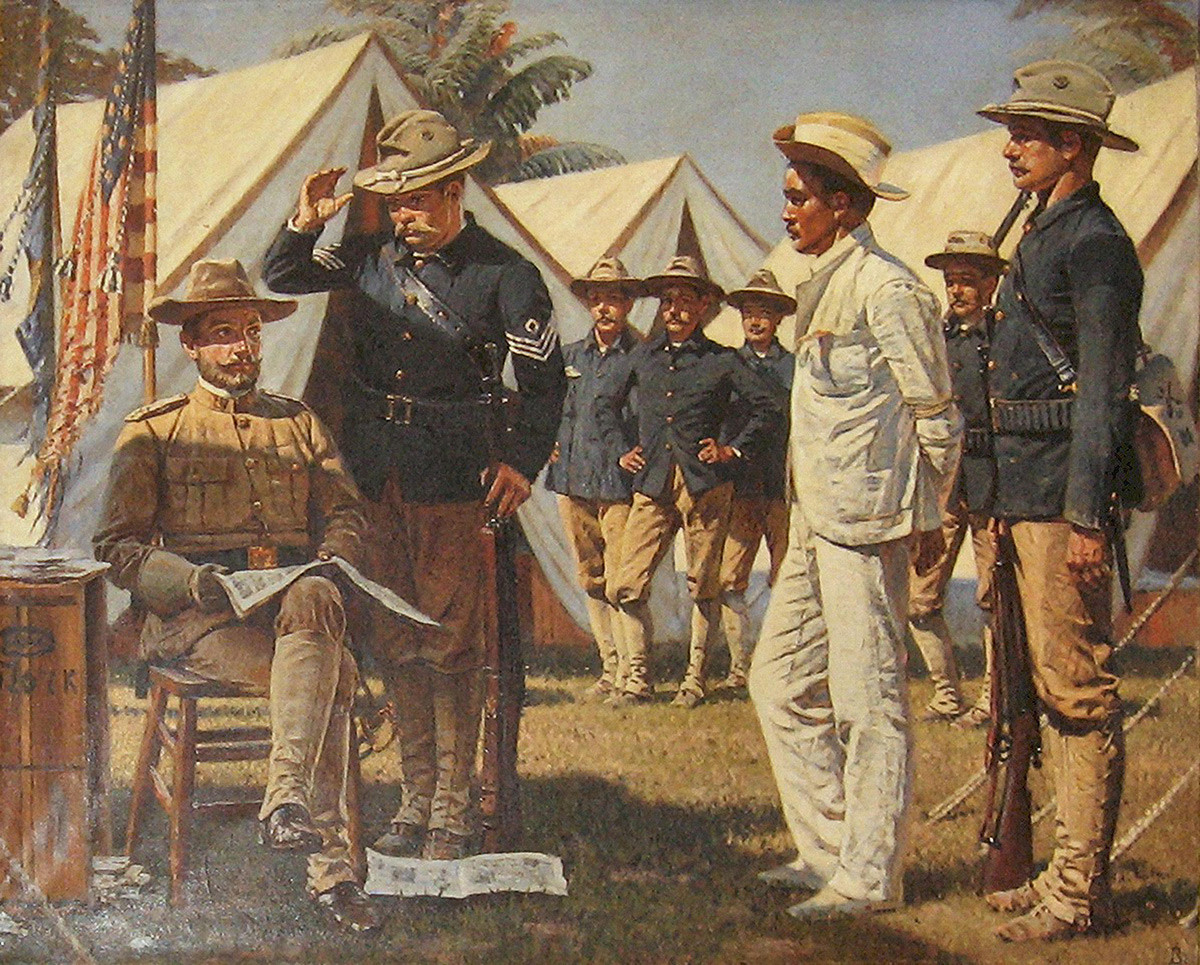

Spy ,1901.

Legion MediaIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox