The media and bloggers have described the Zoya war memorial complex in the village of Petrishchevo near Moscow as the “most beautiful” museum: A minimalist snow-white building appeared here in May 2020, on the spot where young partisan Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was executed and subsequently proclaimed a martyr by Soviet authorities. The enormous building of the modern museum stands among village houses that are half a century old. They did not even have gas until recently - the village was only connected to gas mains this year. In the short period of time since it was constructed, the building, which is very different in appearance from a typical patriotic museum in Russia, has gained popularity on social networks, but has also found itself embroiled in a row.

During World War II, The Soviet Red Army actively joined not only men, but also women and children. Tens of thousands of minors joined the ranks of the resistance, the so-called intelligence and sabotage units.

Commanders did not hide the fact that 95 per cent of members of such partisan groups were essentially destined to die and warned recruits to this effect during their training. Those not ready to die a painful death if captured in the event of an operation going wrong were asked to leave their unit. Eighteen-year-old Zoya, from a family of Soviet teachers, was one of those who, in November 1941, decided to remain in such a detachment.

After successfully blowing up a road, a group of young boys and girls, including Zoya, was transferred to an area near Moscow on a new combat mission: to burn down 10 population centers. Deadline for implementation - five to seven days. The order to set up arson teams had been signed by Joseph Stalin - he argued it was necessary to deprive the German army of the opportunity to live in warm dwellings in occupied villages and towns and instead make them freeze in the open.

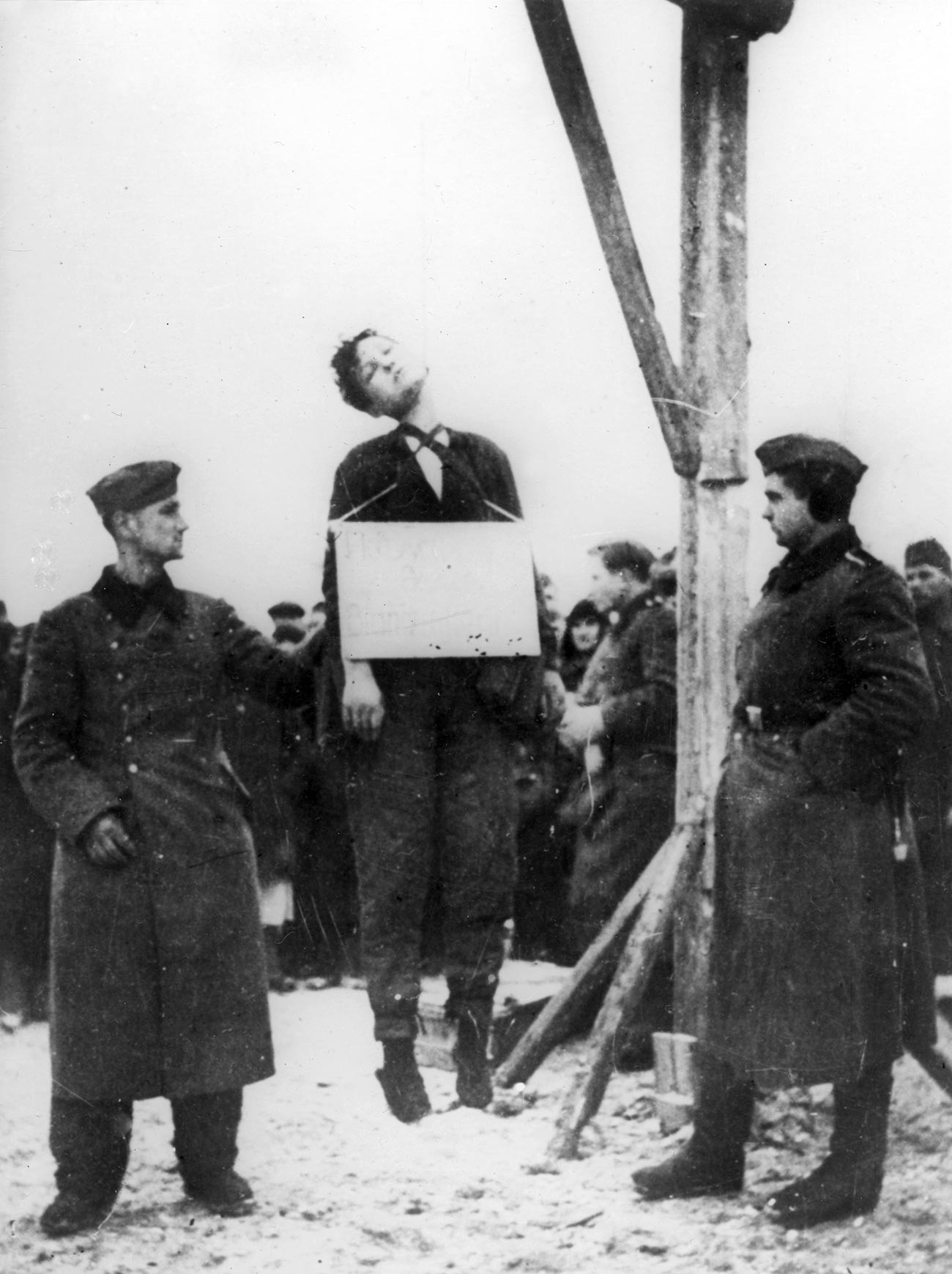

The group successfully set fire to several buildings in the village of Petrishchevo, but when she tried to set fire to another building, Zoya was captured. According to eyewitness accounts, she was stripped naked and flogged with belts, then marched down the street in freezing temperatures in just her underwear. Zoya’s feet were frostbitten and she was kept in this state in a village house until morning, when she was hanged with a board round her neck bearing the inscription in Russian and German: “Houseburner”. Her body was left hanging on the gallows for another month. In December, drunken German soldiers stripped her of her remaining clothes and cut off one of her breasts. Only then was Zoya allowed to be buried outside the village.

Казнь Зои.

Global Look PressThat is what is known for certain about the story of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya. It was war correspondent Pyotr Lidov who broke the story of her heroism and death to the general public. He had spoken to eyewitnesses and, in 1942, wrote an article about her for the Pravda newspaper. In the center of the article was a photograph of the girl’s exhumed body. It transpired from the article, which quoted an elderly peasant, that before she died, Zoya had made a speech about the resilience of the Soviet people and their inevitable victory: “They were hanging her, but she was making a speech. They were hanging her, but she was still threatening them…”

By February 1942, Kosmodemyanskaya had already posthumously become the first woman awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. The authorities saw her story as having a powerful ideological potential for raising the fighting spirit of the Red Army. The image of the partisan martyr as an example of the heroism of Soviet people was quickly elevated to cult-like status and widely publicized. Everyone in the Soviet Union knew about Zoya.

The new museum stands 200 meters from the place where Zoya was initially buried. The eight parts of the museum are connected by a canopy roof set on pillars and as one makes one’s way around the exhibits, every so often, one can glimpse views of the village or open fields.

A snow white museum set among open fields - it is not a random design, but a deliberate choice on the part of the architects.

“We were criticized for our chosen style. We were told that architecture of this kind does not embody those tragic wartime events. But we are of a different view: The building is not meant to embody them. In our view, in the Zoya museum, the architecture is not supposed to import additional meanings to her story,” according to architect of bureau "A2M"Andrei Adamovich, the author of the design concept.

As one comes out of the room dedicated to Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, one can see the place of execution on one side and the house where she was tortured on the other.

There are six interactive exhibition rooms in the museum altogether and not everything in them relates directly to Zoya. The exhibits primarily tell the story of the people of her generation who had to encounter war at such a young age. A room containing a reconstruction of a schoolroom includes recordings of a military announcement and of projectiles in flight, a winter room has the temperature turned down and the story of the Battle of Moscow is told with the aid of a film screened behind a life-size mock-up of a tank.

A room recreating an army canteen contains a display of letters from the front and a recording of reminiscences by Zoya’s relations and contemporaries is constantly played.

And some real food can be had in the museum’s minimalist cafe, where, apart from lattes and muffins, a lunch imitating the menu of an army field kitchen of the 1940s is available: carrot tea and kulesh (a thick meat soup).

Both the building, the cafe and the reception area are in sharp contrast with what can usually be seen in a patriotic museum. “These spaces must be absolutely pure,” say the designers, explaining that they want people to understand that the fortunate times in which we live were largely made possible by these people.

But minimalism and a studied “purity” are appreciated by more than those interested in the story of Zoya. Since the Zoya museum opened, it has become the location of fashion shoots for brands and bloggers.

The popular internet publication The Village has even published an article headlined ‘Place of Kosmodemyanskaya’s execution and the ideal backdrop for fashion shoots’, which sparked a row on social media. Some people find it inappropriate and offensive to hold photo shoots at a place of execution and, indeed, anything connected with the memory of World War II is invariably a rather sensitive subject in Russia. “People, what’s the matter with you? You’ve not only mislaid your consciences, but also your brains,” was how users commented on the sort of people who come to the Zoya museum for the sake of an “ideal backdrop”.

Incidentally, the Moscow Region Ministry of Culture sees nothing wrong in this sort of attention. “We did not set out with the intention of attracting a fashion audience or any other audience. But the fact that the building has proved attractive and that people come here to get photographed is also a good thing,” says minister Yelena Kharlamova.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox