Mikhail Romm started out as an impostor. He became a director by just calling himself one and then actually having to prove to others that he was for real. From the very beginning, the film industry was a battleground for him.

Mikhail Romm liked to experiment with different movie genres.

Tolchan/SputnikHe was born into a Jewish family in the Siberian city of Irkutsk where his father, a physician and bacteriologist, was sent into exile for his revolutionary activities. In 1907, the Romm family was finally allowed to return to Moscow. Mikhail graduated from the Institute of Arts and Technology as a sculptor. After several years in the job he began to get itchy feet.

Romm tried his hand at many forms of art. He wrote historical novels, short stories, children’s tales, newspaper essays, translated works by Zola, Maupassant and Flaubert, tried his hand as an actor at the theater. Eventually, the idea of filmmaking took hold.

In the late 1920s, Romm worked as a freelance researcher on the theory of cinema. Having gained access to dozens of films, he watched them over and over to memorize the most significant features frame by frame. That’s when he began to write his own scripts.

Romm believed that if a person knew what elements a motion picture is made from, he could piece it together himself, like a puzzle. “Why did I decide to take up filmmaking in the first place? I just thought it was something totally irresponsible, kid’s stuff, easy-peasy, you know. Literature, for instance, is a serious matter that requires certain efforts. That’s why I took up film," Romm later recalled, with a twist of irony.

It takes a special combination of selfishness and self-awareness to be a director. Romm proved he had enough of both.

In 1933, he was allowed to make his first silent film, titled ‘Boule de Suif’, (Pyshka) based on Guy de Maupassant’s famous story.

It’s no big secret that during Joseph Stalin’s reign everything had to conform to type. The notion of “social realism”, imposed by Stalin on the heels of Vladimir Lenin’s death, forced many talented artists to create idealistic, rose-colored and often fake pictures of Soviet life. Censorship was widespread and systemic to the point where all books, periodicals, paintings, films, theater performances – everything, including how to sneeze, had to be approved by the omniscient Soviet authorities. Personal style and artistic freedoms were only allowed in micro, nano-doses.

READ MORE: 5 reasons why Soviet writer Maxim Gorky is so great

The founder of the socialist realism literary method and author of ‘The Lower Depth’, Maxim Gorky, watched Romm’s ‘Boule de Suif’ and said it was “a good movie”. But several opponents and critics accused the director of falsely portraying France and the people, claiming that Romm’s film had nothing to do with Maupassant’s 1880 short novel. Criticism was a serious matter during the years of the Great Purge. Millions fell prey to Stalin’s repressions between the 1920s to the 1950s. Even the mildest of criticism could cost a man his life.

Everyone waited for Stalin’s reaction, as he always had the last word. The Soviet leader, who was notoriously unpredictable, made a smart Alec remark. He wondered why anyone would need to compare a novel and a film adapted from it. And it worked. ‘Boule de Suif’ immediately got the green-light, winning accolades overseas. In 1934, Romm’s drama received a prize at the Venice International Film Festival.

Romm liked to experiment with different genres. In 1937, he made ‘Thirteen’, an adventure movie in which brilliant Soviet actress Elena Kuzmina played the only female role. As is often the case with directors and their stars, she ended up as Romm’s wife.

In the late 1930s, Romm switched from Maupassant to the 1917 Revolution leader, Vladimir Lenin. His new film, ‘Lenin in October’ was a biopic, starring the charismatic Boris Shchukin.

His portrayal of the iconic leader became the gold standard of Leninist acting. The shooting lasted from early morning to midnight. It took about two weeks to shoot the entire film whose content was guided by Joseph Stalin. It was scheduled to premiere on November 7, 1937, to mark the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution.

READ MORE: Why did Vladimir Lenin adopt the name ‘Lenin’?

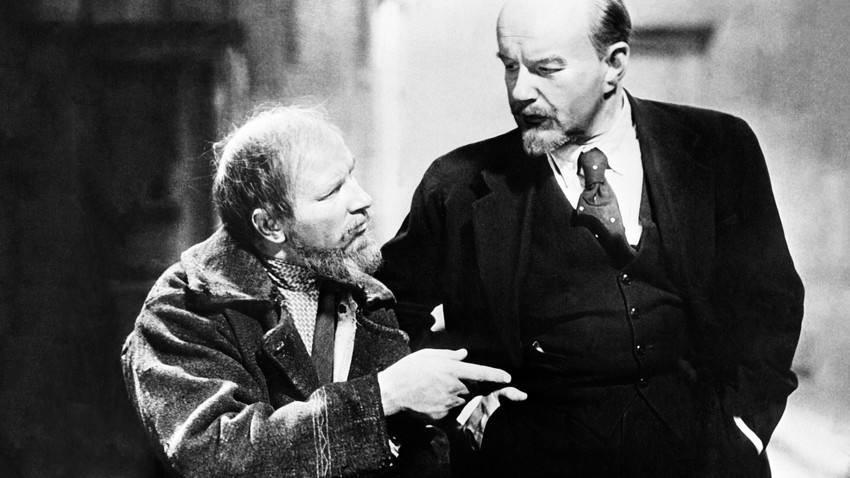

Boris Schukin (right) and Nikolai Okhlopkov (left) in 'Lenin in October'.

SputnikHowever, things went terribly wrong during the premiere of ‘Lenin in October’. There were countless technical problems and the screening had to be interrupted 15 times. When the film finally ended, everyone in the hall waited for Stalin’s reaction with a rather stunned expression. The Soviet leader started to applaud. Those around him burst into cheers and followed in his footsteps. The success of the film was phenomenal. For one, this was the first ever motion picture about Lenin.

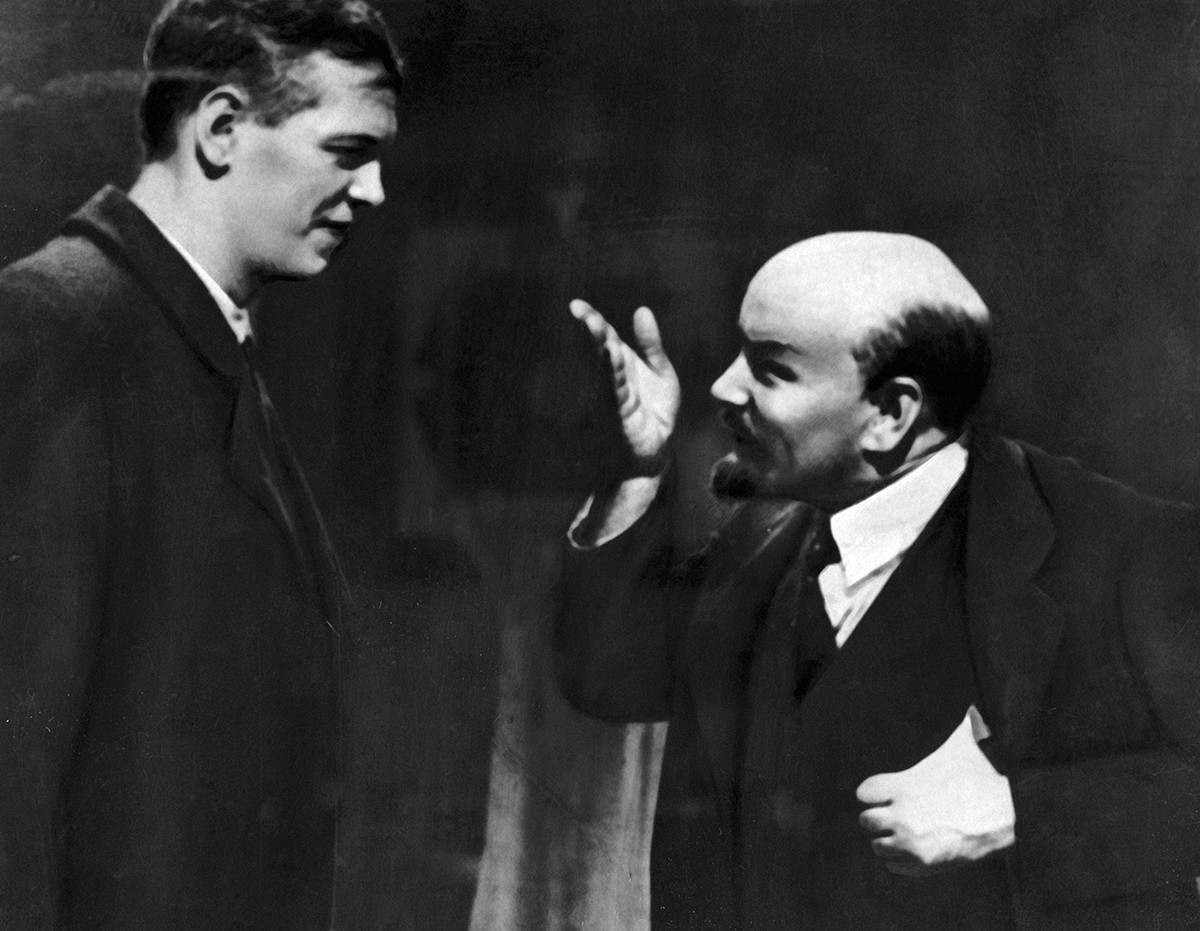

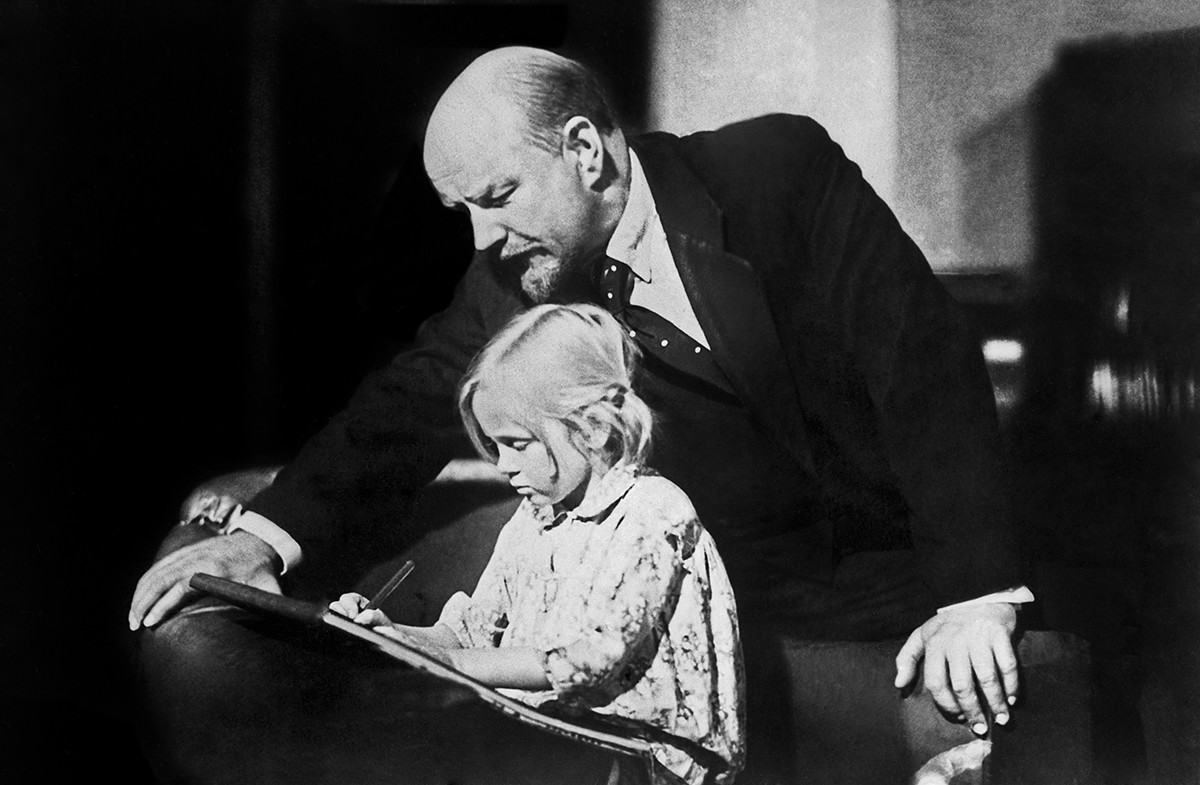

‘Lenin in 1918’ starring the charismatic Boris Shchukin.

SputnikBut in professional cinematic circles, Romm’s peers had mixed reactions to the movie. “This film reminds me of a concert in which an excellent singer sang but her dentist husband arrived on stage to bow," Soviet filmmaker Alexander Dovzhenko said. In his book, Romm was the “dentist”.

Following the release of the film, the director was told to add some more important details to his movie, such as the storming of the Winter Palace in Petrograd and the arrest of the interim government. Romm was basically forced to make another biopic titled ‘Lenin in 1918’, which came out in 1939. He received the top Stalin award for both films.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Romm re-edited both Lenin movies, removing all Stalin references.

“A director is someone who presides over a series of accidents,” great American filmmaker Orson Welles once said. Romm got over his films about Lenin and turned over a new leaf. In the early 1940s, he made his timeless masterpiece ‘Dream’, starring Faina Ranevskaya.

Faina Ranevskaya in 'Dream' directed by Mikhail Romm.

Mikhail Romm/Mosfilm, 1941Her portrayal of Madame Rosa Skorokhod, a toxic authoritarian woman who runs a boarding house, catapulted the genius actress to fame.

The movie was an international success, reaching audiences on the other side of the Atlantic, including then U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Romm long tried to decode the ghastly and barbaric nature of fascism. A really good understanding of history and psychology helped him dig deep enough to make unorthodox movies.

Mikhail Romm

Mikhail Ozersky/SputnikIn 1944, Romm unveiled his new drama ‘Girl No. 217’, starring Elena Kuzmina. It detailed the story of a young Soviet woman transported to Germany and enslaved by fascists.

Tatiana Krylova is sold into slavery for 15 marks. The woman finds herself in an ordinary German family, where she is treated like an animal. She has no human name, no past and no future, only a number. After the Nazi occupation of the Soviet Union in the early 1940s, the Germans used millions of Russians, Ukrainians and Byelorussians as forced workers (or Ostarbeiters, literally “workers from the East”).

Romm received another Stalin award for the movie, which he co-wrote with his favorite friend and scriptwriter Yevgeny Gabrilovich. In 1946, it also scooped the Grand Prize of the Authors' Association for Best Director at the First International Film Festival in Cannes.

This was the first, but not the last, time Romm attempted to trace the origins of German fascism. Several of his movies, including ‘The Secret Mission’ (1950) and ‘Murder on Dante Street’ (1956), depicted the rise of fascism, violence and oppression.

Romm could finally breathe freely during the cultural thaw of the Khrushchev years. Like a great prophet, he foresaw the rise of science in the USSR. In the early 1960s, he released his new drama, ‘Nine Days of One Year’. An absolute gem of a movie, it was like a fresh start and an opportunity to restyle himself.

Alexei Batalov and Innokenti Smoktunovsky in 'Nine Days of One Year'

Mikhail Romm/Mosfilm, 1962‘Nine Days of One Year’ revolved around a pair of nuclear scientists: a great idealist and a die-hard cynic. Dmitry Gusev (played by Alexei Batalov) comes to grips with the consequences of his work after being exposed to lethal radiation during an experiment at a secret lab in Siberia. The sands of time are running out. His idealism may be futile, but he wears it like a medal. His friendly foe rival (played by Innokenti Smoktunovsky) is meanwhile the epitome of skepticism.

Romm’s movie won a Crystal Globe Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 1962.

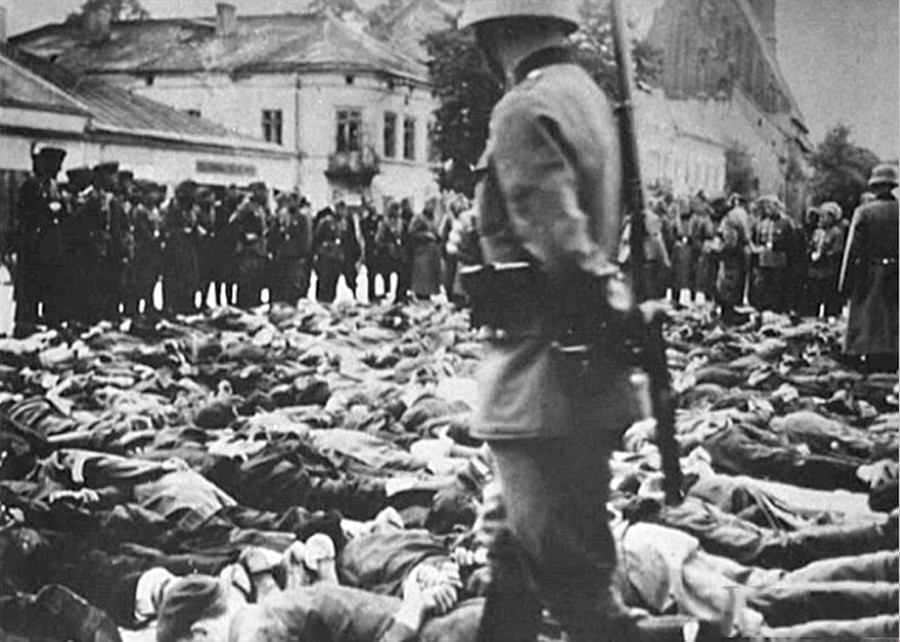

In 1965, Romm made a movie that defined a decade or, rather, a century. His magnum opus, entitled ‘Triumph over violence’ (Obyknovenny faschizm) was narrated by Romm and co-written by Maya Turovskaya and Yuri Khanyutin.

It’s an in-depth documentary about the horrors and origins of fascism. Romm pushed back the boundaries of human despair with his unconventional film, awash with lurid imagery, mostly drawn from the Nazi archives as well as Hitler’s personal archive.

The documentary exposed both the Soviet Union’s totalitarian system and the crimes of the Nazi Germany during World War II, drawing parallels between the two devastating evils.

“I remember perfectly well the times when the very idea of comparing fascism and communism would strike me as blasphemous. However, when ‘Triumph over violence’ revelatory documentary came to be released, most of my friends and I totally subscribed to the director’s hidden agenda --- to show a terrible, unconditional, and an infernally deep similarity between the two regimes,” iconic Soviet sci-fi writer Boris Strugatsky recalled.

READ MORE: 7 Russian documentaries you MUST watch

In his powerful documentary, Romm used all visual means out there, from music to archival footage, to deconstruct and scrutinize total tyranny and human tragedy. Some of the images are graphic and profoundly disturbing. The director looked each person in the eye, be it the eye of the victim or the aggressor.

‘Triumph over violence’ (Obyknovenny faschizm)

Mikhail Romm/Mosfilm, 1965 "Third Creative Association"In Soviet times, the film was withdrawn from wide distribution and was briefly banned from regular cinemas after the Second Secretary of the Communist Party, the guardian of Soviet ideology Mikhail Suslov, posed a rhetorical question to the director: “Mikhail Ilyich, why do you dislike us so much?” The answer, of course, was in the film.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox