In the last two weeks of every June, St. Petersburg experiences one of its most celebrated natural phenomena - the White Nights, a time of near-midnight sun. Fans of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, whose bicentennial is being marked in 2021, enjoy going for an evening walk on a summer night when a patch of daylight is visible in the city for all but a brief moment of time.

Strolling past the canals and riverside promenades, a reader cannot help but wonder if a particular building is indeed the same one that Dostoyevsky wrote about when he walked these same streets in the 1840s. The nameless narrator in the short story White Nights guides the reader through parts of the city that have not changed much since the peak of its imperial glory.

The story of an innocent young man and the love he feels for a woman he meets on the streets of St. Petersburg was translated into several languages and moved several film directors who interpreted Dostoyevsky’s writings in their own way.

In 1957, Luchino Visconti, one of the fathers of Italian neorealism, directed Le notti bianche (White Nights), which has since become one of the classics of international cinema. Instead of mid-19th century St. Petersburg, the movie is set in the Tuscan city of Livorno. There is no first person narration of events, but viewers are introduced to Mario, played by the legendary Marcello Mastroianni and Natalia, played by leading Austrian-Swiss star Maria Schell.

Mario seems to be a lot older than the narrator in Dostoyevsky’s story and Natalia is depicted as far less innocent than the writer’s Nastenka. Filmed on a set in Rome’s Cinecittà, the director, whose theatrical production of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment was well received in Italy, wanted to have a set that was a hybrid of a film and theater set. He used expressionist lighting and stage effects during the studio shooting.

“In the movie, Visconti balances formal elements like lighting, montage, camera movements, costuming, special effects and set-design to highlight the complexities of melodramatic tension that matures between the male and female leads,” Brendan Hennessey, a professor of Italian wrote in the January 2011 Italian issue of Modern Language Notes, an academic journal of John Hopkins University.

The movie won the Silver Lion Prize at the 18th Venice International Film Festival in 1957.

Seven years after Visconti’s movie became popular around the world, German journalist-turned director Wilhelm Semmelroth attempted to make a more authentic version of the short story, closely following the text. Semmelroth, who was known for making appearances in his own movies much like Alfred Hitchcock, directed Helle Nächte (Bright Nights) in a special production for WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln or West German Broadcasting Cologne). Semmelroth, who adapted the works of William Shakespeare and Thomas Wolfe into telefilms, preferred to work with lesser-known actors.

The narrator in the story is named Fyodor, with the assumption that Dostoyevsky’s story was autobiographical. Nastenka’s lover has more than just a small but important part that comes in the short story. The 75-minute black and white movie was broadcast on WDR in July 1971 and received critical acclaim, but it did not travel past Germany. Unfortunately, it seems to have been lost, with WDR employees expressing complete helplessness when contacted for a print. The movie stands out, as it was one of the rare attempts from West Germany to understand Russia during the peak of the Cold War.

An award-winning 2017 German movie of the same name is not based on Dostoyevsky’s story.

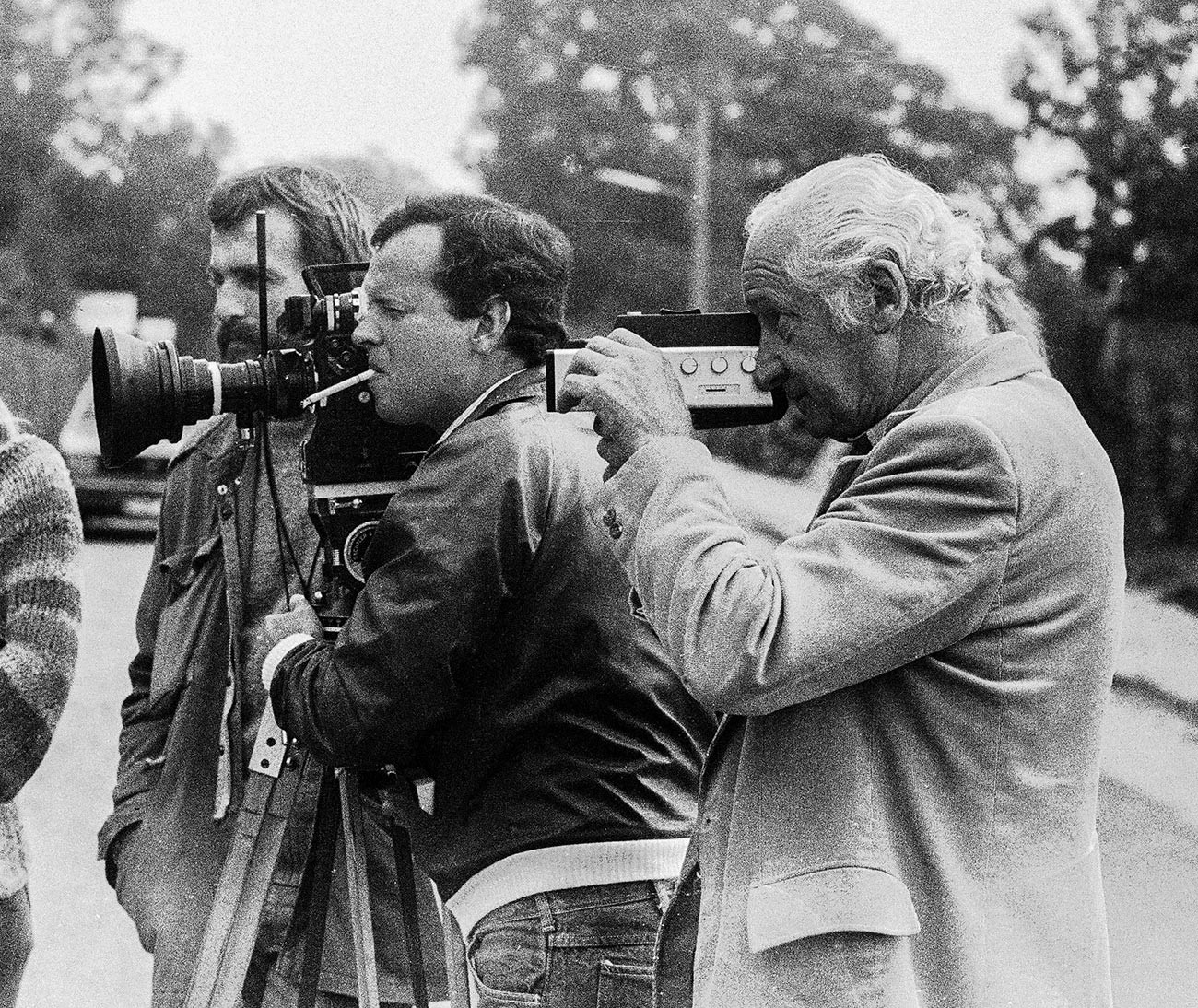

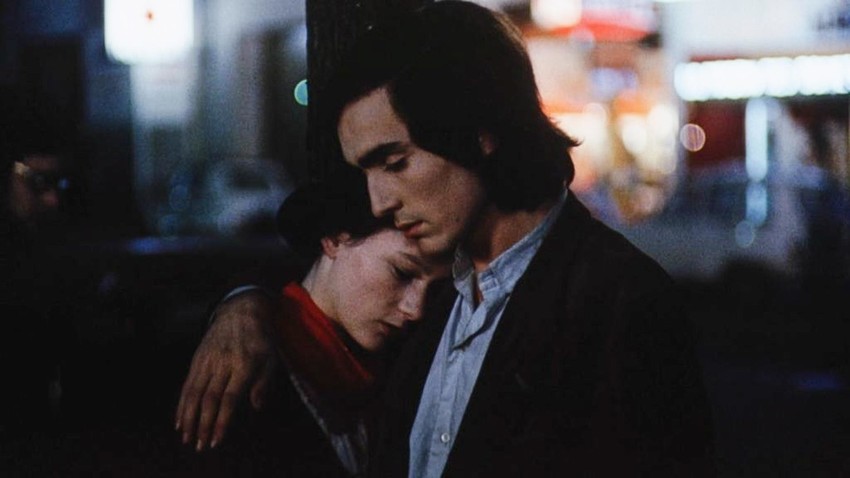

French director Robert Bresson, one of the pioneers of minimalist films, directed Quatre nuits d’un rêveur (Four Nights of a Dreamer) in 1971. This adaptation of the Russian writer’s story is mostly set in Paris. Bresson mostly worked with non-professional actors and Jacques, who is Dostoyevsky’s narrator, is played by Guillaume des Forêts in a very believable performance as a Parisian artist. Well known actress, model and photographer Isabelle Weingarten plays the French version of Nastenka – Marthe.

If the story’s narrator happened to get transplanted to the dreamy Paris of the early 1970s, he would have probably been just like the bohemian Jacques. The romance of the artist and the lonely woman, who lives with her mother (unlike Nastenka, who is with her grandmother), is beautifully portrayed through nighttime sequences in the city. The romance of the narrator and Nastenka’s time together is also well depicted with Marthe and Jacques walking on the streets, promenades and bridges of Paris, complete with the hallucinatory light and color of the city of love.

It was screened at the 21st International Berlin Film Festival in 1971.

A Portuguese adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s story for Brazilian audiences was the brainchild of Poland-born Zbigniew Ziembiński, a Jewish-Polish refugee who fled the Holocaust and migrated to Brazil. In 1941, when he arrived in Rio de Janeiro, Ziembiński did not speak a word of Portuguese, but by the end of the decade he would become a leading theater director. He continued to have an illustrious career over the next three decades.

In 1973, he directed Noites Brancas (White Nights) a tele-film that was shown across Brazil. The film stars legendary Brazilian actor Francisco Cuoco in the role of Dostoyevsky’s narrator and Nívea Maria, who is best known as a soap opera actress in Brazil. Nastenka’s elusive lover is played by Cláudio Cavalcanti, who was also a writer, singer and producer. Like the German television adaptation of White Nights, the film runs close to Dostoyesky’s story. A full-length version of the film is difficult to trace. Given the closeness of the Portuguese and Italian languages, Visconti’s version enjoyed greater popularity in Brazil than the local version.

Several Asian directors have adapted Dostoyevsky’s story to the silver screen, with many productions in Indian languages. Most of the Asian movies localize the story the way Visconti and Bresson did.

South Korea’s Jung Sung-il in one of the great debuts directed 카페 느와르 (Ka-pe-neu-wa-reu or Cafe Noir), which is a two-part movie that adapts Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther and Dostoyevsky’s short story. He was a well known film critic in the country before he chose to direct movies.

The second part is an adaptation of the Russian story with the protagonist Young-soo, a music teacher having a chance meeting by a bridge with Sun-hwa (Jung Yu-mi). The plot, more or less, follows Dostoyevsky’s story and ends up with the young man heartbroken when the woman he covets happily walks into the arms of her elusive lover. Only in this movie, the young man loses out twice, with a similar sad ending in the first part. The more cohesive second part does full justice to Dostoyevsky’s writing.

The movie, which was released in 2009, did the rounds at several festivals in Asia and Europe, including in Hong Kong, Venice, Copenhagen and Los Angeles. Its success mirrors the rise of Korean cinema and the growing international popularity of Korean culture.

When Dostoyevsky wrote this story in the 1840s, little could he have imagined the way it would travel to far corners of the planet. It will always be a quintessential St. Petersburg story, but a reader in any part of the world cannot help but feel for and relate to both the narrator and Nastenka. The joys, yearnings, passion, obsession, sorrow, anxiety, bliss and heartbreak in the story are all things that human beings face at some point or other in their life. For the Russophiles around the world, the last two weeks of June will always be about the White Nights in St. Petersburg, both the natural phenomenon and Dostoyevsky’s story.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox