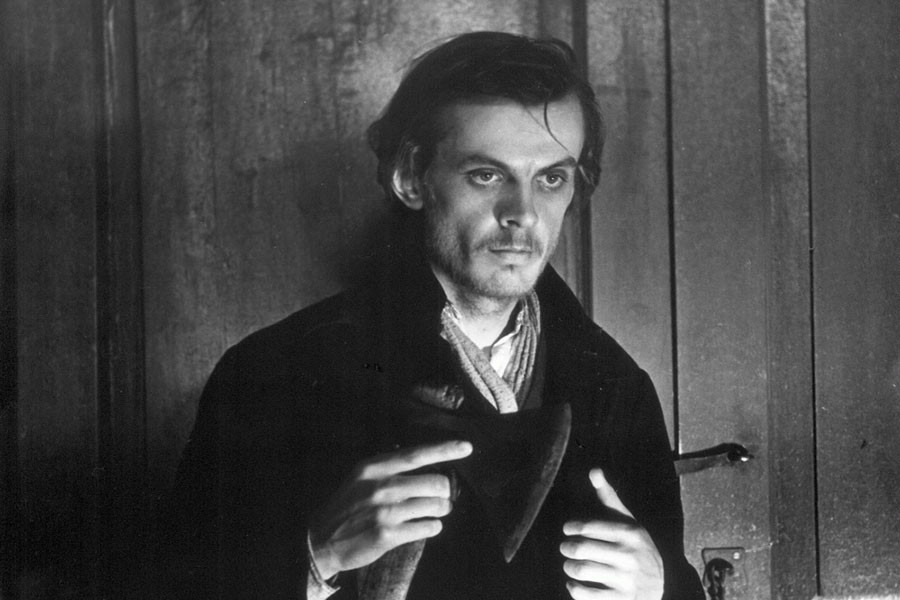

Actor Georgy Taratorkin as Rodion Raskolnikov.

Lev Kulidzhanov/Gorky Film Studio, 1969The charismatic character created by Fyodor Dostoevsky is a morally ambiguous man with a broken soul.

“Am I a trembling creature or have I the right,” Raskolnikov boldly asks himself. Why does he commit such a cruel, but, at the same time, cowardly crime? Perhaps, because he is both the villain and the victim? Raskolnikov goes through emotional hell in his quest for moral freedom and pays for his crime for the rest of his life. “I didn’t kill the old woman, I killed myself!” Raskolnikov explains in ‘Crime and Punishment.’

READ MORE: 5 reasons why Dostoevsky is SO great

His intelligence, sincerity and honesty make him so real that you think you have met him in the flesh!

Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, from ‘War and Peace’ by Leo Tolstoy, is a sophisticated character endowed with romantic yearnings. With his head in the clouds of idealism and optimism, he dreams of military glory and genuine love. The theatricality of high society seems false and worthless to Andrei Bolkonsky. “How was it that I did not see that lofty sky before? And how happy I am to have found it at last!” Prince Andrei says, lying wounded on the ground during the Battle of Austerlitz. “All is vanity, all falsehood, except that infinite sky. There is nothing, nothing, but that. But even if it does not exist, there is nothing but quiet and peace. Thank God…!”

READ MORE: Is classic Russian literature really so depressing?

The central character of ‘Fathers and Sons’ by Ivan Turgenev is an incorrigible nihilist and a rebel without a cause.

Ironic, cynical and sharp, Bazarov speaks his mind without reservation and fear. The young man doesn’t recognize art and romance (“A decent chemist is twenty times more useful than any poet,” he says); doesn’t believe in love and marriage (“…love… this is an imaginary feeling…”) and seems to have his own opinion on everything. Unmerciful and uncompromising, Yevgeny Bazarov became a role model to a generation of nihilistic young Russians, who welcomed his ideas and hopes for the future.

The eponymous hero of Alexander Pushkin’s epic novel in verse ‘Eugene Onegin’ is young, rich and restless.

The handsome nobleman cares about his appearance and can easily spend three long hours getting ready for the ball in front of the mirror. Ladies’ man Onegin is an aristocratic bon vivant of the first order. Shallow, single and pushy, he doesn’t save money and knows how to seduce women.

With womankind, the less we love them,

the easier they become to charm,

the tighter we can stretch above them

enticing nets to do them harm.

READ MORE: Top 5 most likable Russian characters in western literature

Cold, calculating and good-mannered, Nikolai Gogol’s Chichikov knows how to make a good impression on complete strangers.

The swindler arrives in a small town in the middle of nowhere with the aim of buying… “dead souls”, the deceased peasants listed only on paper. His fraudulent scheme is designed to make Chichikov rich. However, his dreams are not destined to come true. “If you want to get rich soon, you will never get rich; if you want to get rich without thinking about time, you will get rich soon,” Gogol remarks in his magnum opus, ‘Dead Souls’. In fact, Before Alexander II ordered the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, landowners in the Russian Empire could buy, sell or even mortgage serfs. The word ‘soul’ was used to refer to serfs when counting their exact number.

The most memorable fictional characters are sometimes the ones least willing to act. That’s exactly the case with Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov.

Ilya Ilyich spends most of his time lying on the couch. His laziness is ridiculous, his bed is his cave, 24/7. The moment the nobleman is about to get active, he calls Zakhar, his servant, and continues to fritter away time in bed. What willpower! Oblomov catapults innate laziness to the top tier of procrastination. And he can afford it! His philosophy is simple: Why make things better when it’s easier to put up with things the way they are. “When you don’t know what you are living for, you live somehow day after day; you rejoice that the day has passed, that the night has passed and, in your sleep, you will immerse yourself in the boring question of why you have lived this day and why you will continue to live tomorrow.”

The hero of Boris Pasternak’s iconic novel ‘Doctor Zhivago’ towers over those around him morally and ethically. A brilliant diagnostician, he is a thoughtful man of action and principle.

Doctor Zhivago doesn’t understand people who are always on the right track. “I don't think I could love you so much if you had nothing to complain of and nothing to regret. I don’t like people who have never fallen or stumbled. Their virtue is lifeless and of little value. Life hasn’t revealed its beauty to them.”

Alexander Chatsky, of Alexander Griboedov’s ‘Woe from Wit’, is smart, witty, and very lonely.

The eloquent three-thinker of liberal views returns to Moscow from three years abroad, dreaming to reunite with his childhood love, Sophie. But it’s too late. The young woman has fallen in love with Molchalin, a scoundrel whom Chatsky detests and despises. Chatsky simply can’t accept the fact that Sophie chose a dumb, callous man over him. He speaks out against the hypocrisy of aristocratic society and decides to leave Moscow for good.

Away from Moscow! Catch me being here again!

I’ll go around the world in search

Of a place with room for outraged feeling! . .

In the mid-1920s, Professor Preobrazhensky, of Mikhail Bulgakov’s ‘The Heart of a Dog’, embarked upon an unprecedented and gruesome experiment.

The world-renowned surgeon transplants a human pituitary gland into a stray dog that found its new home in his spacious, seven-room Moscow apartment. The poor animal transforms into a real bastard, the Bolshevik type of man who only drinks, smokes and swears. “The most horrible thing is that he no longer has a dog’s heart, but a human heart. And the lousiest of all that exists in nature.” Professor Preobrazhensky, a member of the refined Russian intelligentsia who hates the Soviet proletariat, would eventually have to acknowledge that some experiments are better left alone.

Ostap Bender, from ‘The Twelve Chairs’ by Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, is the most famous conman in Russian literature.

His reputation precedes him. The “great schemer” and habitual liar is familiar with around “four hundred relatively honest ways of taking other people’s money”. The biggest challenge of his adventurous life is to find one of the twelve chairs filled with diamonds sewn into its seat. A brilliant rogue, Bender hopes to strike it rich and move to sunny Rio de Janeiro. “The time that we have is the money we don't have.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox