Sergei Yesenin in 1916 (left) and in 1924

Russia Beyond (Lev Ivanov, Sputnik)A village youth arrived in sprawling St. Petersburg in poor peasant clothes and carrying only one modest travel chest. Straight from the station, he went to look for the place where his idol lived - the famous poet Alexander Blok. Just to see him...

This is just one of the many myths that Sergei Yesenin invented about himself. In the early 20th century, the world of Russian poetry was overcrowded with talented poets (and not only them), so in order to become famous, one had to resort to tricks and myth-making. Basically, you had to jazz it up and find a way to market yourself in order to stand out. This was how Yesenin carefully cultivated his image as a maverick peasant poet.

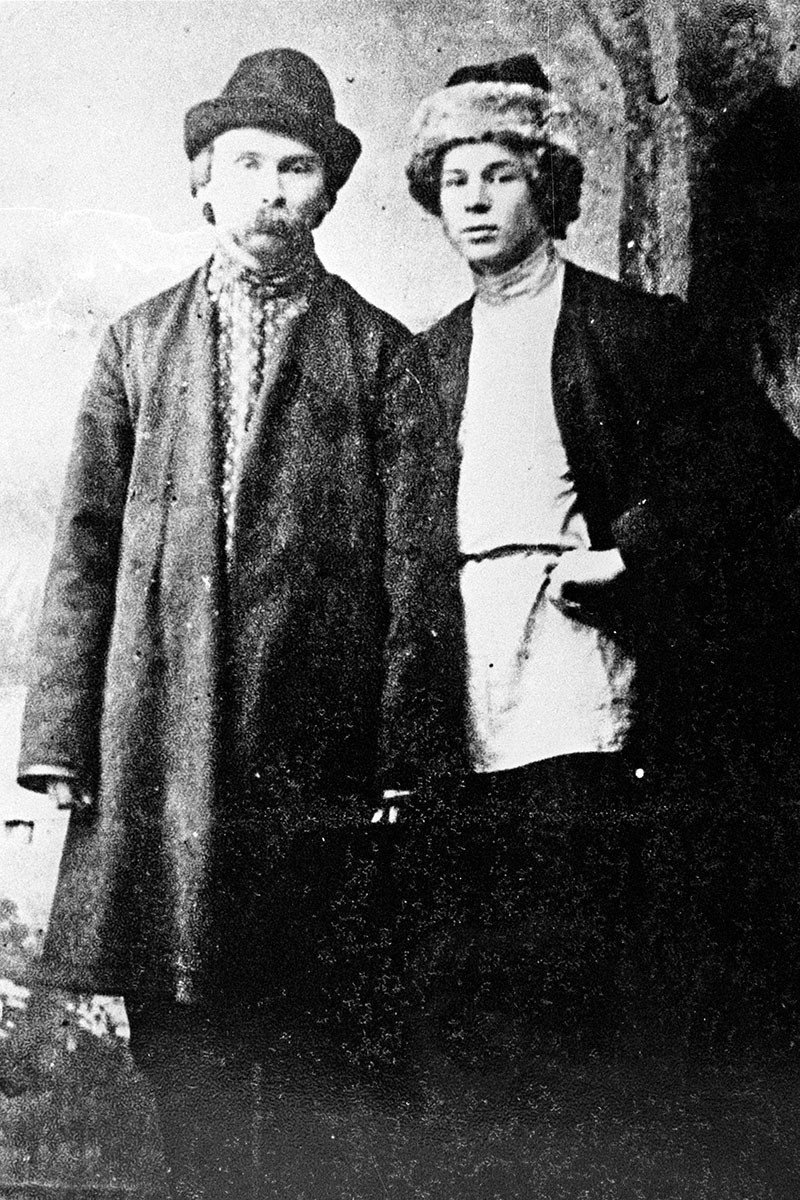

“New peasant” poets: Sergei Yesenin (right) and Nikolai Klyuev, 1915

Public domainIn fact, he did come from a village, but his family was far from poor, and Yesenin dressed quite well. In addition, he had a fine education. Before coming to St. Petersburg, he had lived in Moscow for several years, where he attended a public school as a non-matriculated student, and worked in a printing house. Yesenin’s poems were already published in magazines. One of his first published poems was a verse that every modern Russian child today knows by heart. It starts like this:

“Just below my window

Stands a birch-tree white,

Under snow in winter

Gleaming silver bright.”

(Translated by Peter Tempest)

It was probably Yesenin who gave birth to the all-consuming love that Russians have for birch trees, open fields, golden rye, “bonfires of red mountain ash”, and “golden groves”. He called Russia “a country of birch chintz”, and the theme of his homeland with its boundless expanses and rural landscape is an ever-present motif in his poetry, with a constant nostalgic tinge. Yes, he lived in Moscow and St. Petersburg - but, boy, did he miss his native village. Aristocratic poets of the 19th century saw and depicted nature differently: they admired it, but not with such poignant anguish.

Yesenin did in fact visit Blok in St. Petersburg, although he first sent him a polite note informing the famous poet of his visit. After their meeting, Blok left the following entry in his diary: “A peasant from the Ryazan province, 19 years old. The poems are fresh, clean, vociferous, wordy. Language. He visited on March 9, 1915.”

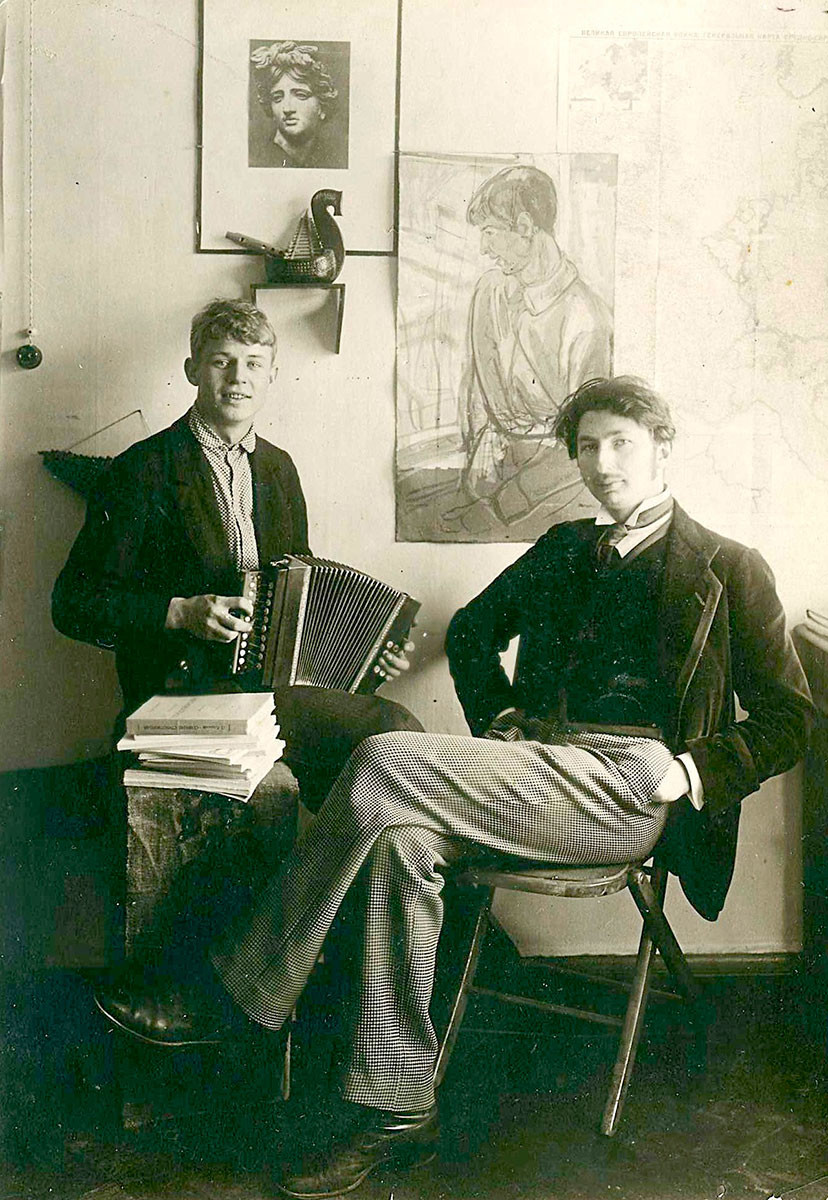

Poets Sergei Yesenin and Sergei Gorodetsky, 1916

Public domainYesenin's friend Anatoly Marienhof would later write, citing the poet, that he never wore peasant dress: “I had never worn such reddish boots in my life or such a bedraggled coat as the one I wore to meet him”, and that he “had come to St. Petersburg in search of global fame, and a bronze monument”. Well, he did find fame, and much of it. For patriotically-minded Russians, Yesenin today remains their favorite poet.

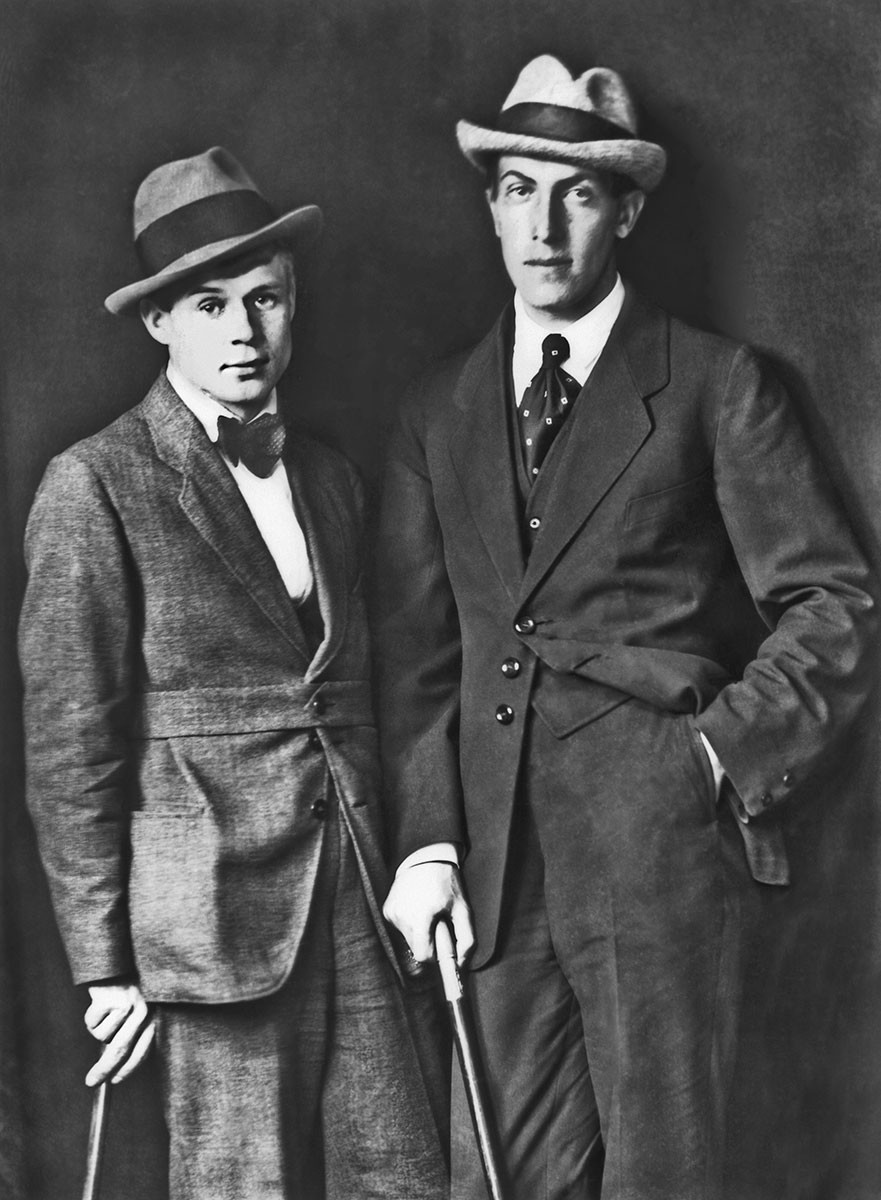

In 1918-1919, Yesenin became friendly with a circle of eccentric Imaginist poets. From a “simple country boy” he turned into “a hooligan” and “a cheeky Moscow mischief-maker”, and swapped his simple country dress for a tailcoat, a top hat and a cane. In his poems, he celebrated “Moscow of taverns” and talked about his reputation as “a brawler”.

To be fair, Yesenin's real life was true to his poetic image - he drank and spent much of his time in taverns, brawling and fighting – thus developing a certain reputation. However, there was always a certain sadness present - the wretched reveler missed home and hated himself for his lifestyle. While it seemed he was losing himself, there was a hope that love could save him.

Imaginist poets Sergei Yesenin and Anatoly Marienhof, 1923

N.Svishchev-Paola/TASSThe young poet was busy looking for that salvation, as evidenced by his eventful love life - several unsuccessful marriages, several abandoned children and the many women left with a broken heart. Among them was famous American dancer Isadora Duncan. He went with her on a tour of Europe and the United States, but could not stand being in her shadow, and so, soon they broke up. His last wife was Sophia, a granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. For many years, after yet another failed liaison, he returned to his secretary, Galina Benislavskaya, who was in love with him, although her love was unrequited. After his death, she followed him and committed suicide on his grave.

Sergei Yesenin and Isadora Duncan

Public domainIn Confessions of a Hooligan, Yesenin wrote that his outrageous behaviour was deliberate and that he loved to be castigated. He once again professed love for his Motherland, and asked his village ancestors whether they knew that “their son was the best poet in Russia!”

At the time of the Bolshevik Revolution, Yesenin was in Moscow, but his comments on the political developments in Russia were very few and cautious. It seemed he could not find a place for himself in the whirlwind of events taking place, and so, he began to drink again, imploring in his poems, “the guitar to play and the gypsy woman to sing”. He sought to forget himself, and to forget those terrible days, for which he often had problems with the police.

He watched the horrors of the Russian Civil War, and experienced the widespread hunger and cold in the chaos that engulfed Moscow. But what he cared about first and foremost was not the outcome of this conflict but the fate of his beloved homeland: “My native country from end to end, / Is being torn by internecine discord / Flashing with fire and sabers.”

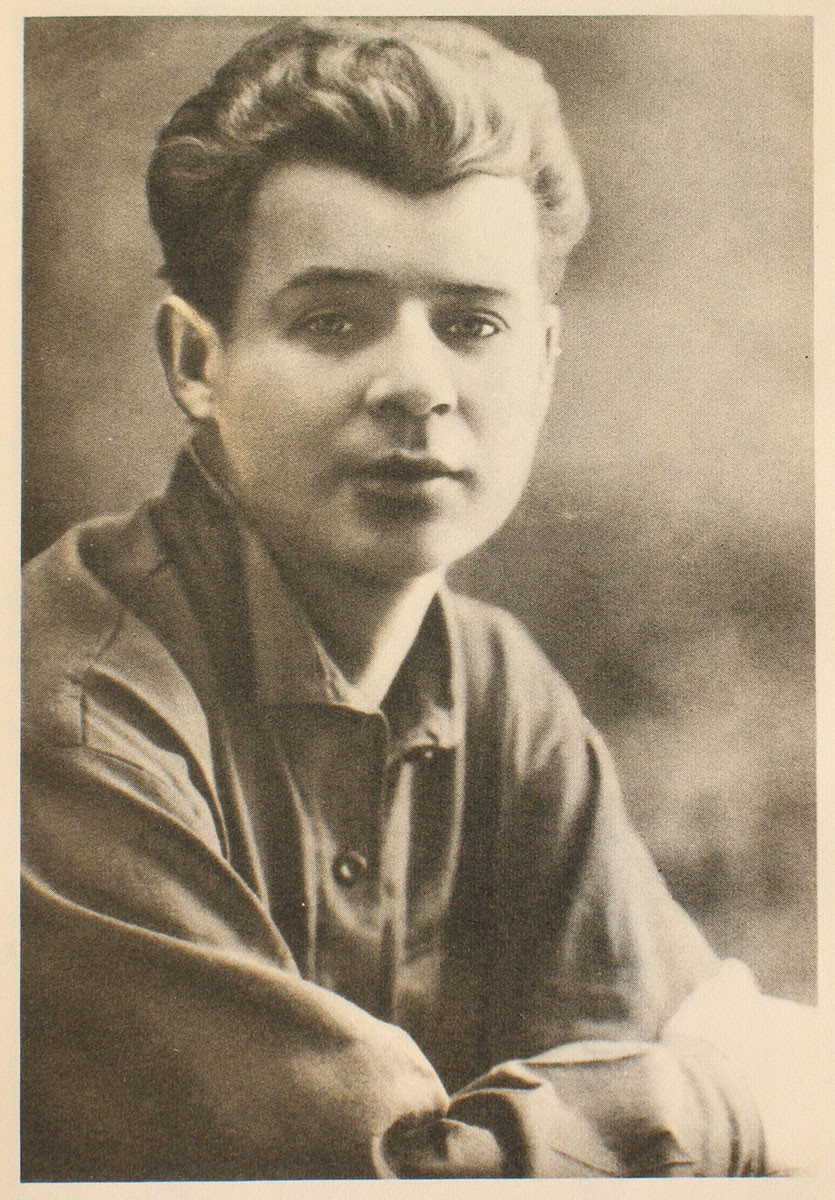

Sergei Yesenin, 1924

Public domainYet, he sided with the Bolsheviks. Before the Revolution, he recited his poetry to the imperial family, but he thought that, as a representative of the common people, he should side with the Soviet regime. In 1924, he wrote that he wanted to be a worthy son of the “great states of the USSR”. But he also said that no matter what wars raged on the planet, what animosity different tribes felt for each other, he would still devote his entire poetic soul to celebrating “that one-sixth of the globe with the short name Rus.”

In a 1923 poem, Yesenin asked those who’d be with him in his last minutes of his life, “to put him under the icons in a Russian shirt to die”. However, his actual death was different from what he had asked for. Furthermore, there is still no universally accepted theory of how exactly the leading peasant poet died.

Sergei Yesenin

SputnikThe official version is suicide. On December 28, 1925, Yesenin hanged himself in a room at the Angleterre Hotel in Leningrad. He left a poem, written in blood (there was no ink), “Goodbye, my friend, goodbye”, which has the line: “In this life, dying is nothing new.”

In the 1970s, however, an investigator with the Moscow Criminal Investigation Department put forward a theory that Yesenin was killed by state security officers, who then staged his suicide. The main evidence in support of this theory was a hematoma on the poet's face (it is clearly visible in the posthumous photos), which the investigator considered a likely sign of a violent death. Maybe Yesenin, in a throwback to his tavern brawling past, fought with the people who came to kill him.

A posthumous photo of Yesenin

Public domainThis theory added another exciting and tragic dimension to the poet's image, so it’s not surprising that it was embraced by popular culture, resulting in several films and TV series made about Yesenin's death.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox