If Kazimir Malevich made a radical step into abstraction and developed Suprematism, a new, non-objective form of painting, his colleague El Lissitzky took the ideas of the avant-garde to a different, three-dimensional level. He introduced Suprematism to architecture.

Soviet engineer, architect and artist El Lissitzky was much better known abroad than at home. Among his colleagues and friends were Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger, Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy and other artists at the cutting edge of the international art scene. This passionate adherent of Suprematism had a great influence on the founders of the Bauhaus and on Constructivism throughout Europe, where Lissitzky studied and lived for a long time.

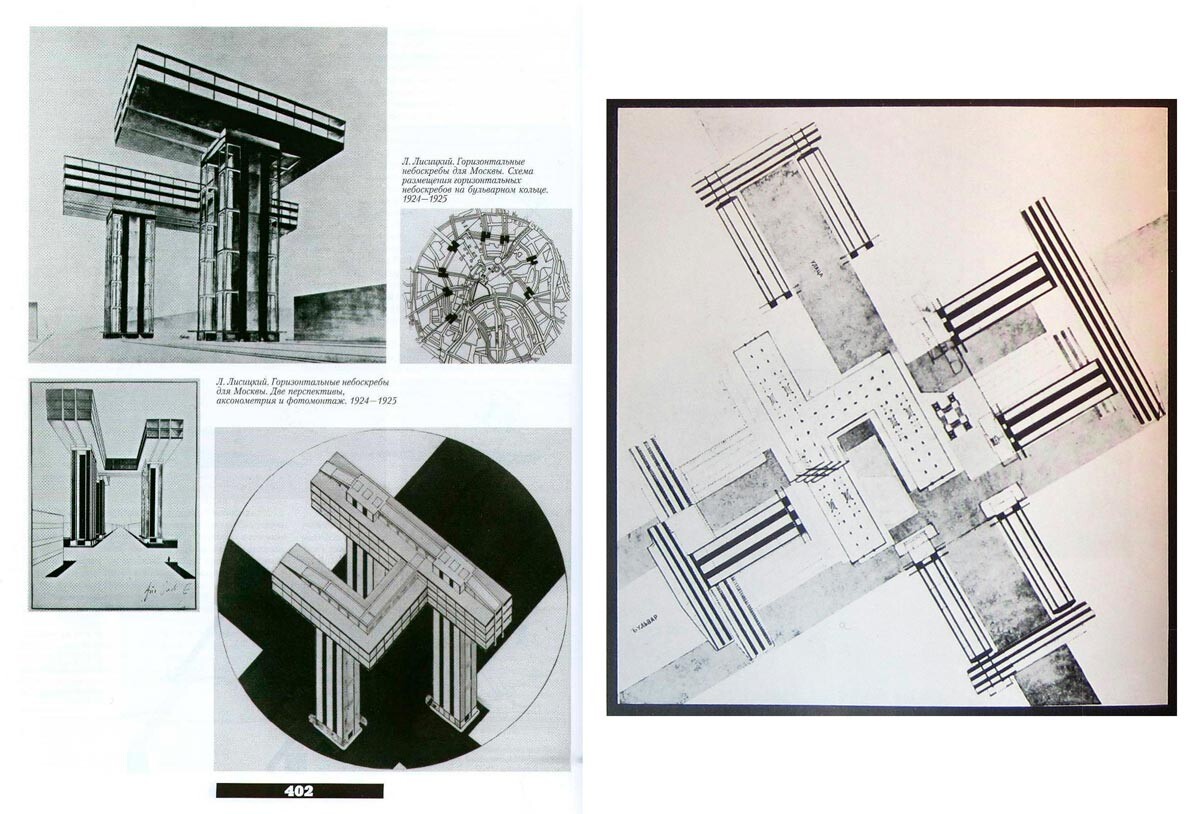

He was forced to return to Russia at the outbreak of World War I. From that moment on, he was to apply his creative energies to “Russian material”. In 1924, he came up with a grand plan for the construction of eight identical buildings in Moscow - the first Soviet “skyscrapers”. The grandeur of the idea lay in the fact that the skyscrapers were supposed to extend not vertically but horizontally.

This was the real architecture of the future, Lissitzky believed.

In his thinking, Lissitzky was a real Futurist. Innovative ideas concerning different spheres of life came to him all the time. For instance, he predicted the merging of the city and agriculture and the emergence of alternative energy sources.

He also believed that the concept of an individual house should become a thing of the past. In its place would come autonomous mobile housing (something like a multitude of housing communes in public use scattered around the city; everyone could live in one and then exchange it for another, according to their circumstances).

The horizontal skyscraper project was one such “project of the future”. El Lissitzky took exception to the “classic” American skyscraper as a concept. “This type [of architecture] has developed completely anarchically, with no consideration for overall urban planning. Its only concern was to upstage its neighbor in height and splendor,” he wrote in 1926 in the Izvestiya Asnova journal, published by the creative association of Soviet rationalist architects (it was the first and only issue of the journal).

In it, he described the gist of his design. El Lissitzky wanted to implement the idea of a two-level city: through the use of vertical piers, a building would be erected with the smallest possible footprint and no damage to the environment.

“If a particular plot lacks the space for a horizontal layout at ground level, we can hoist up the required useful floor space on piers <...>. The aim is to achieve a maximum of useful floor space with a minimum of supporting structure underneath,” he wrote.

The eight buildings of concrete and glass on Moscow’s Boulevard Ring were designed to house Soviet ministries and departments. The architect intended to raise each skyscraper 50 meters above street level. The piers were to house lifts and stairs giving direct access to the Moscow Metro or to an above-ground public transport stop.

For all their progressive modernity, the skyscrapers were, in the end, not built. “Our mistake,” El Lissitzky recalled, “was that we wanted to move straight to a technology that did not exist yet - I wanted to create an architecture that broke free of its foundations and soared in the air defying the force of gravity.” In other words, it was an idea whose time had not yet come.

El Lissitzky’s other architectural projects included a textile plant, a yacht club, a communal block of apartments and a publishing house for the Pravda newspaper, but the only one that saw the light of day was the Ogonyok printing house on 1st Samotyochny Lane in Moscow.

Ogonyok printing house

Sergei Dorokhovsky (CC BY-SA 3.0)Nevertheless, as an architect El Lissitzky is remembered for his skyscrapers. The illustrator and founder of @ANOVISATE studio Konstantin Anokhin studied the architect’s drawings and showed what these avant-garde edifices would have looked like today in the locations where El Lissitzky himself had planned to build them.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox