The Gulag & Stalin’s purge in Pyotr Belov paintings (PICS)

The Great Lenin, 1985

Gulag History MuseumWhen these paintings were first displayed to the public in Moscow in 1988, spectators were so impressed that people stood in long lines to get to the exhibition.

![The Rooks Have Arrived [refers to the famous 19th century painting with the same name by Alexei Savrasov]](https://mf.b37mrtl.ru/rbthmedia/images/2022.01/original/61e92939ee1edf75a84579a5.jpg)

The Rooks Have Arrived [refers to the famous 19th century painting with the same name by Alexei Savrasov]

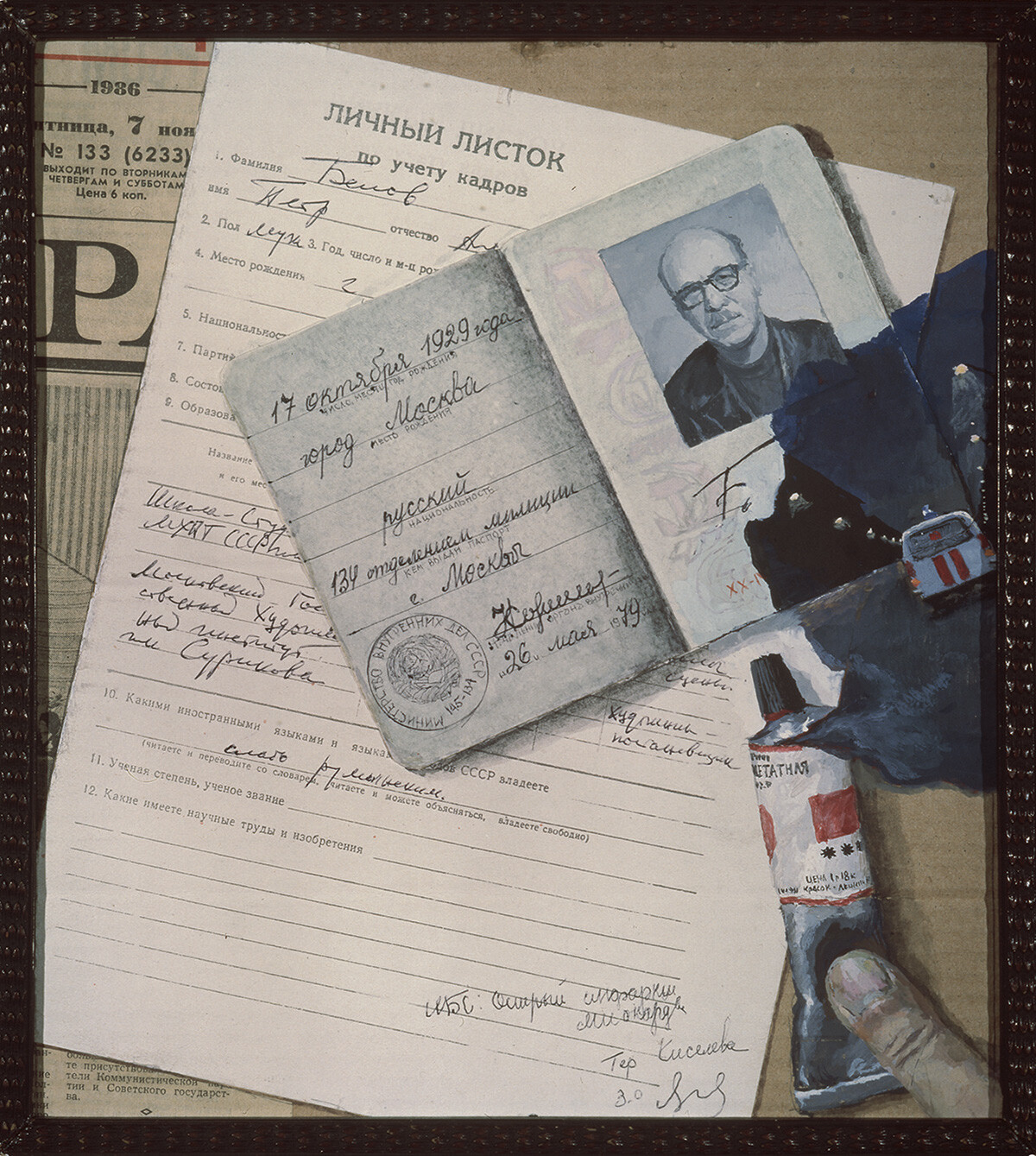

Gulag History MuseumPyotr Belov, then an unknown artist, immediately became the symbol of perestroika and glasnost in art and the symbol of the changes when kitchen talks and whispers became a part of public space. Before, speaking (let alone painting) on the topic of Stalin’s repressions was almost impossible. And rarely did books about the Gulag reach publication.

Heart Attack, 1986

Gulag History MuseumAfter that, Belov’s paintings went on a whole tour around the Soviet Union and became very recognizable. In 2020, the family of the artist gifted his paintings to the GULAG History Museum in Moscow. The institution gave them a second life, exhibiting them - and let the people comprehend the emotions that their compatriots went through in the late 1980s.

Dandelions, 1987

Gulag History Museum“The cycle of paintings that deeply impressed the audience with its bravery and depth was immediately called the ‘anti-Stalin cycle’,” says Roman Romanov, director for the Gulag History Museum.

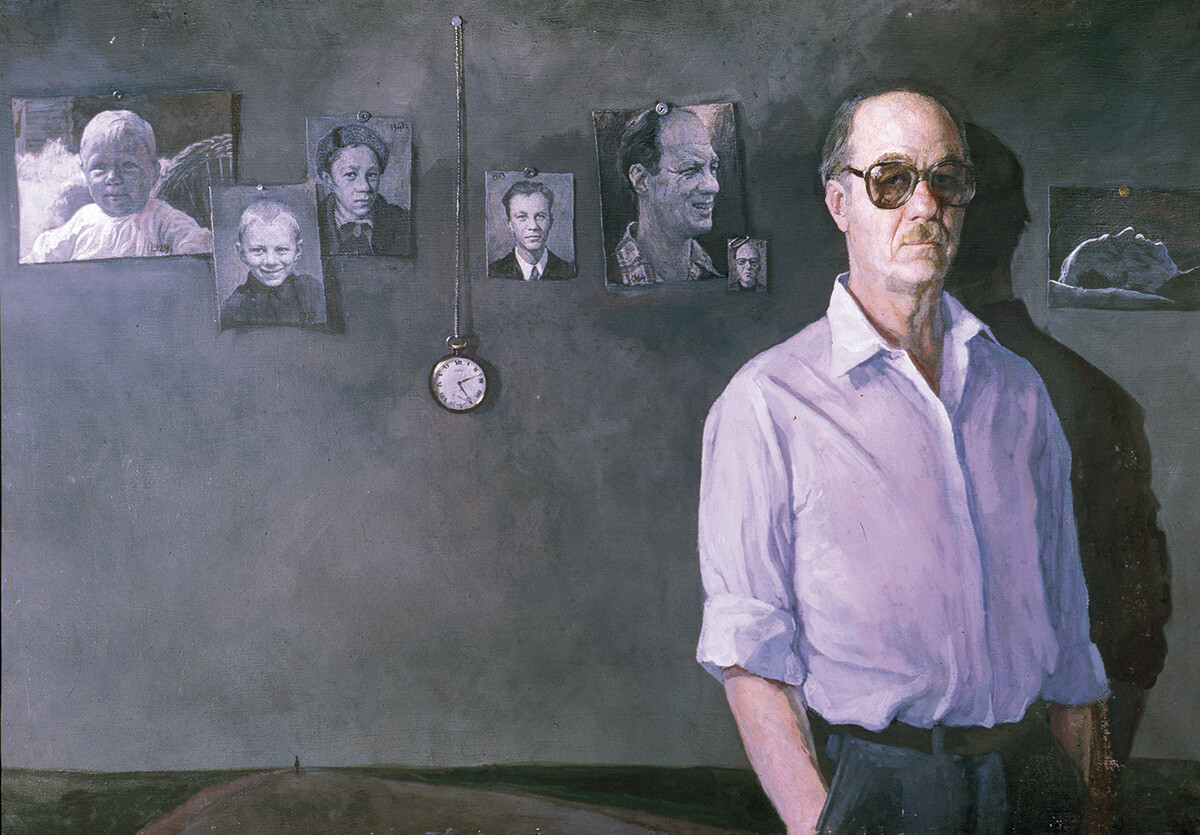

Entire Life, 1987

Gulag History Museum“His works expressed innermost grief and fear understood by many contemporaries. He managed to show the sharp dissonance relatable to the experiences of millions of fellow countrymen,” Romanov adds.

Untitled. (Ascension), 1987

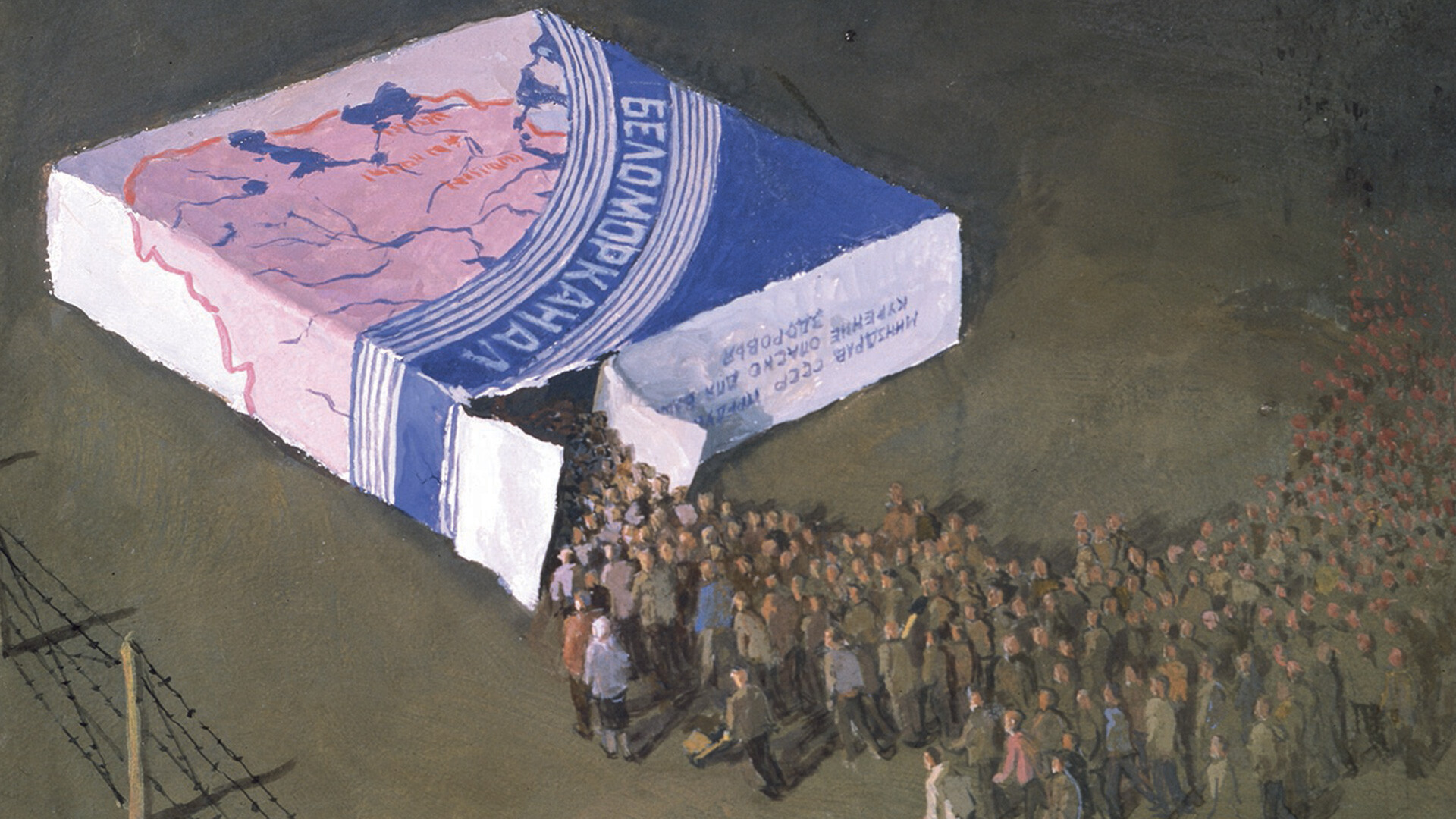

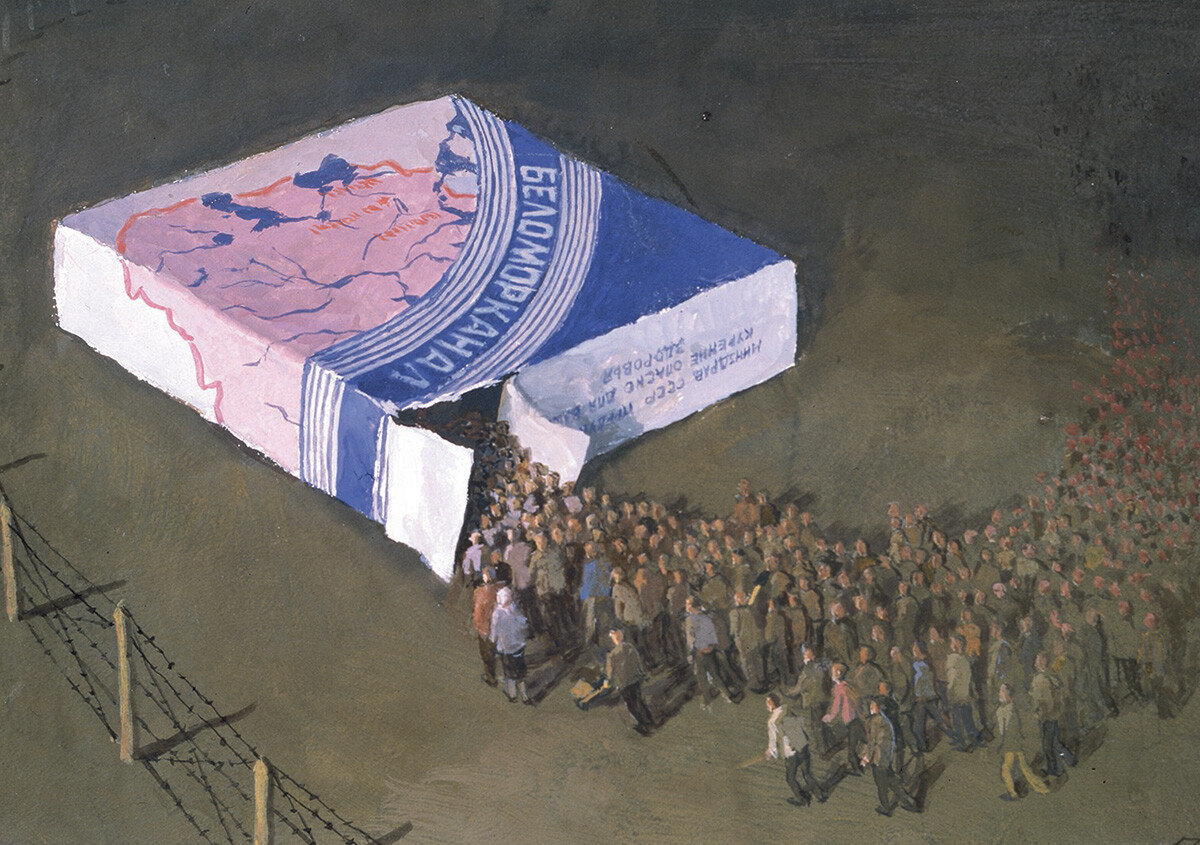

Gulag History MuseumThe painting below shows a case of cigarettes called ‘Belomorkanal’ (or just ‘Belomor’ in slang) after the White Sea-Baltic canal. The canal is infamous for being built by Gulag prisoners in record time and the construction works in tough conditions took several thousands of lives. So the metaphor is clear: many people went through the Belomorkanal.

Belomorkanal, 1985

Gulag History MuseumA metaphor of Pasternak being immured in the wall is very true-to-life. When his novel ‘Doctor Zhivago’ was banned in the USSR, he secretly transferred it to the West. The piece was published in the West and the author received the Nobel Prize for literature. But the Soviet authorities launched a whole bullying campaign against Pasternak, which led to his premature demise. At the bottom lies a Pravda newspaper with a portrait of Nikita Khrushchev, who initiated the bullying.

Pasternak, 1987

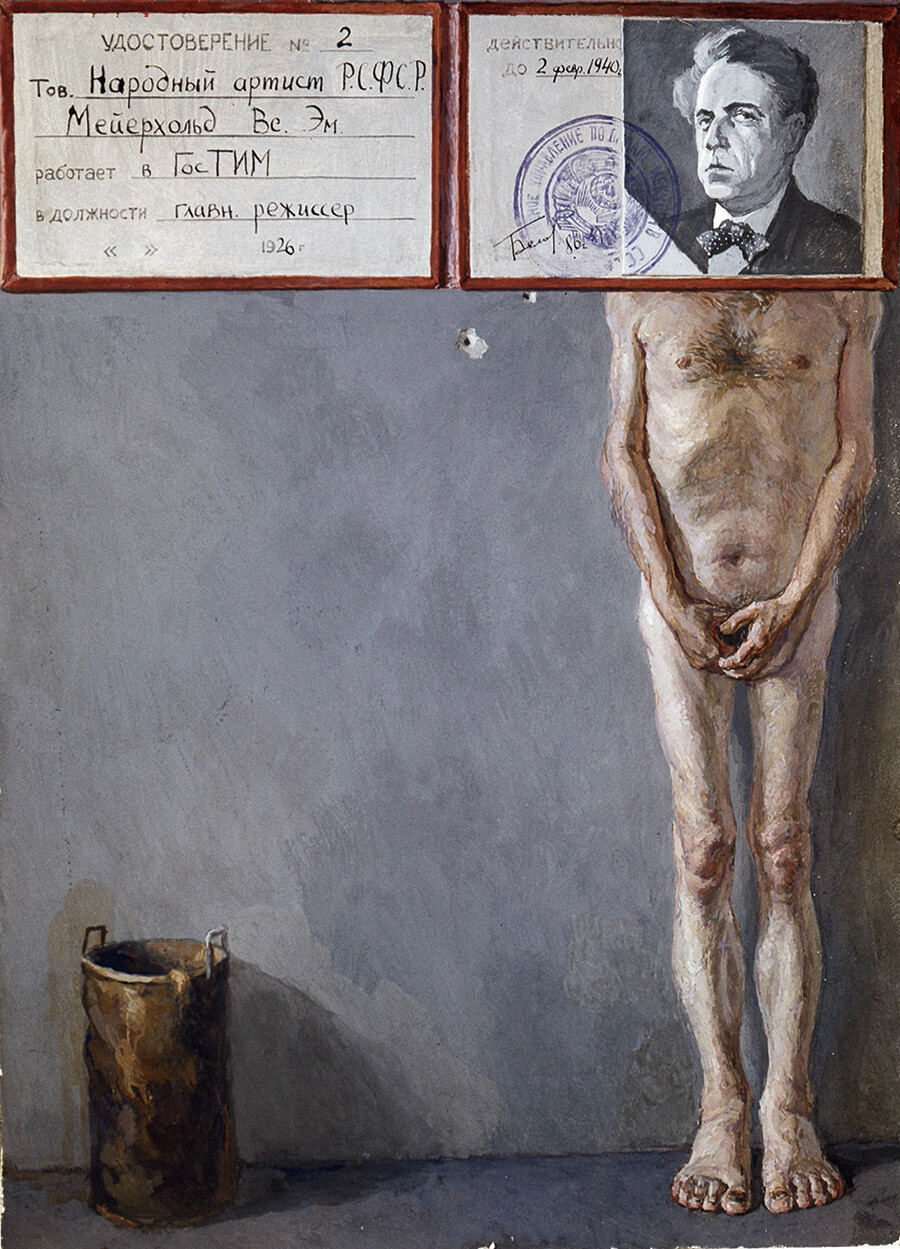

Gulag History MuseumThis painting refers to the repressed theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold. Belov pictured the emaciated, battered body in prison, while the head is covered with the portrait photo of an official identification pass.

Meyerhold, 1986

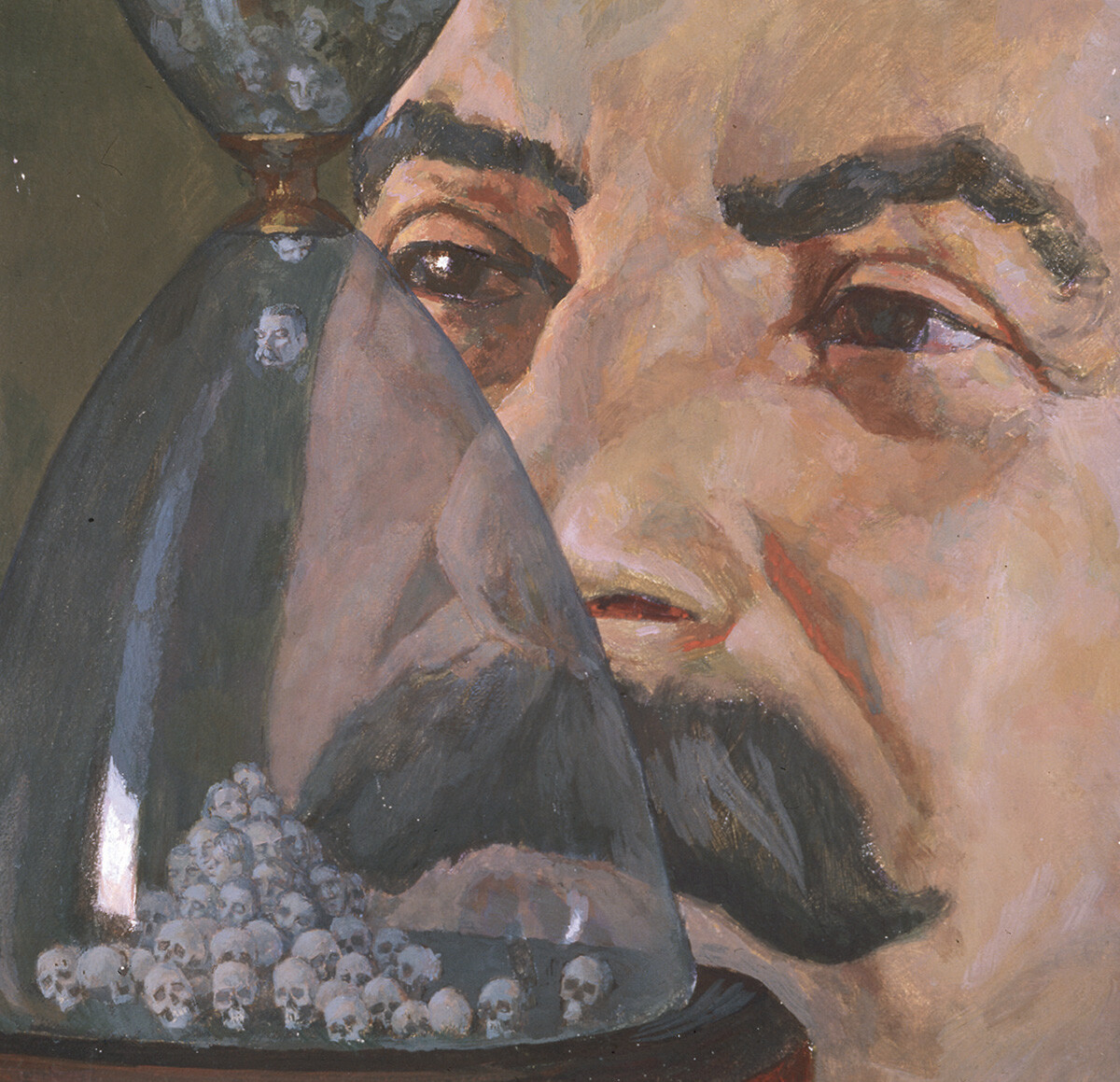

Gulag History Museum“Stalin in paintings by Belov is an allegory of death,” says Kirill Svetlyakov, the exhibition’s curator. “In one of the paintings, he is looking at the hourglass where human skulls ‘measure’ time instead of sand grains. In another painting, human figures resemble ashes and fall out of his pipe. In the next one, people are wildflowers under the dictator’s boots.”

The Year 1941, 1985

Gulag History Museum

The Sandglass, 1987

Gulag History Museum“The precise examination [of the painting below] reveals a photograph in the thawed patch... on which we recognize dad’s forehead and the first page of the manuscript of ‘The Master and Margarita’,” Yekaterina Belova, the artist’s daughter recalls. “We can also see a photograph turned upside down. It surely has mom on it — her hairstyle and hair. And then comes a big snow field. Dad used to say that if one were to start digging and melting the snow, it could show many hidden manuscripts in each thawed patch... Here, it was hardly cleaned and there are lots of unexplored things ahead...”

Thawed Patch. M. Bulgakov, 1986

Gulag History Museum‘Queue for the Truth’ exhibition of Pyotr Belov in the perestroika era is on display in Moscow’s Gulag History Museum until May 18, 2022.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox