We’ve already written about the most prominent contemporary female writers to pay attention to, and now it is time to look at the history of Russian literature and see what place women occupy in its pantheon.

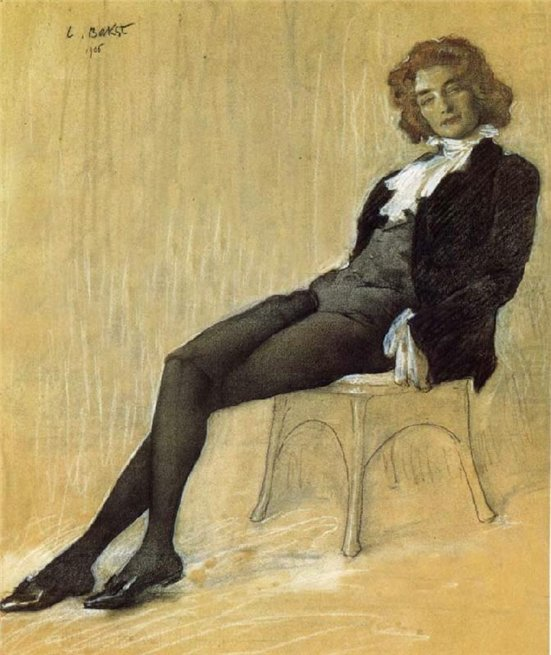

Zinaida Gippius

Public domainOne of the first Russian feminists, Gippius tried to break both gender boundaries and stereotypes about women. She loved to shock the public by showing up in masculine dress, and she would talk about herself in masculine terms, especially when it came to her poems. But at the same time she would wear stunning feminine dresses.

Like her husband, the writer Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Gippius was a philosopher, advocated spiritual freedom, free love, and became one of the ideologists and bright proponents of Russian Symbolism in poetry. “I love myself as God,” she scandalously wrote in her poems focusing on individualism.

Leon Bakst. Portrait of Zinaida Gippius, 1906

Tretyakov galleryTheir apartment at Murusi House in St. Petersburg was the mecca of the city’s creative intelligentsia. After the 1917 Revolution, the couple fled to Paris, where they continued to be bastions of Russian culture, uniting their compatriots who also had to leave their homeland. In the Soviet Union, Gippius's decadent poems weren’t published.

Read more about Gippius here.

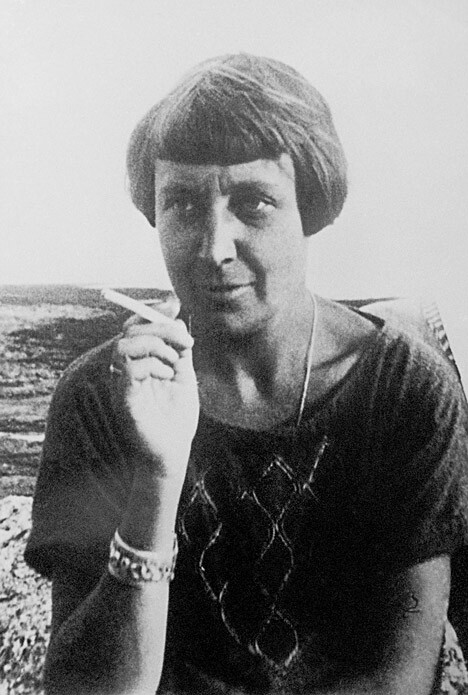

Marina Tsvetaeva, 1925

Peter Shumov/Public domainTsvetaeva's genius was largely influenced by her environment. She was born in Moscow into a creative family, surrounded by music and art. Her father was an art historian, professor and founder of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts; her mother was a talented pianist. Perhaps that’s why Tsvetaeva's poems are very musical, and creativity is inseparable from her life.

Her biography is full of tragedies: Tsvetaeva's daughter died of starvation during the Civil War. After emigrating, Tsvetaeva returned to the USSR in 1939. During Stalin's great purge, her husband was arrested, and her other daughter spent 15 years in the Gulag and exile. Tsvetaeva later committed suicide.

Marina Tsvetaeva in France

TASSReflecting the difficult life she endured, her poems consist of nervous, broken lines featuring a constantly tossing and suffering person. At the same time, her stanzas are filled with a stunning frankness of feeling and passionate love.

The poem, “I like that you are not sick of me”, is set to music and can be heard in the popular Soviet-era New Year's comedy film, “The Irony of Fate.”

Read more about Tsvetaeva here.

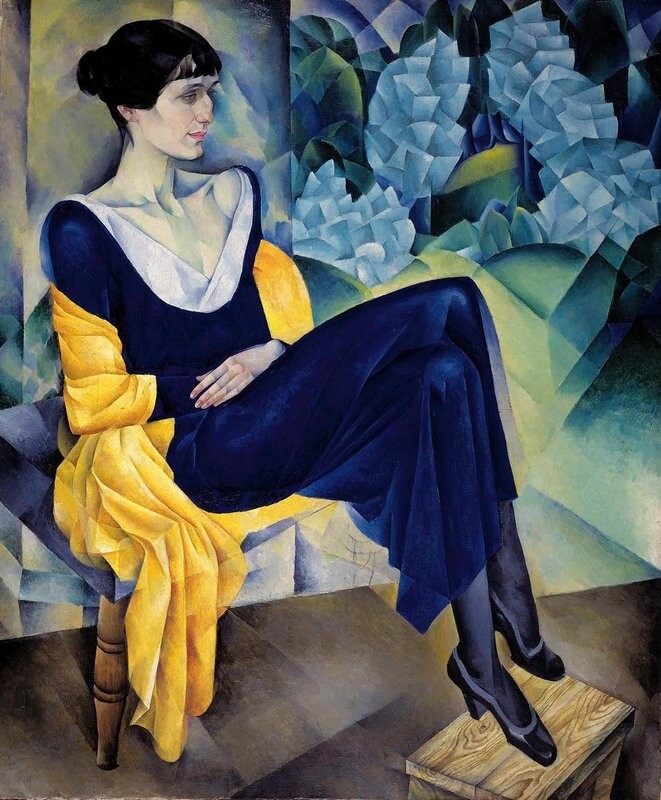

Anna Akhmatova, 1922

Moisei Nappelbaum/SputnikTsvetaeva stands alongside Akhmatova in greatness. While extremely different, they formed the poetic language of an entire century. Akhmatova's early poetry is also about dramatic love feelings, though later it became more lyrical and focused on the fate of the Russian people and the country.

Akhmatova suffered through the state repression of her husband, poet Nikolai Gumilev, and the arrest of her son, historian Lev Gumilev. She survived the Siege of Leningrad and the long years of a ban on the publishing of poetry. Akhmatova's most famous poem, “Requiem”, reflected desperate Soviet women standing clockwise in a line to the office of the secret police and trying to learn about the fate of their arrested sons and husbands.

Nathan Altman. Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, 1914

Russian MuseumAkhmatova’s unusual profile became her hallmark, and her portraits were painted by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Amadeo Modigliani, Nathan Altman and many other artists of the era.

Read more about Akhmatova here.

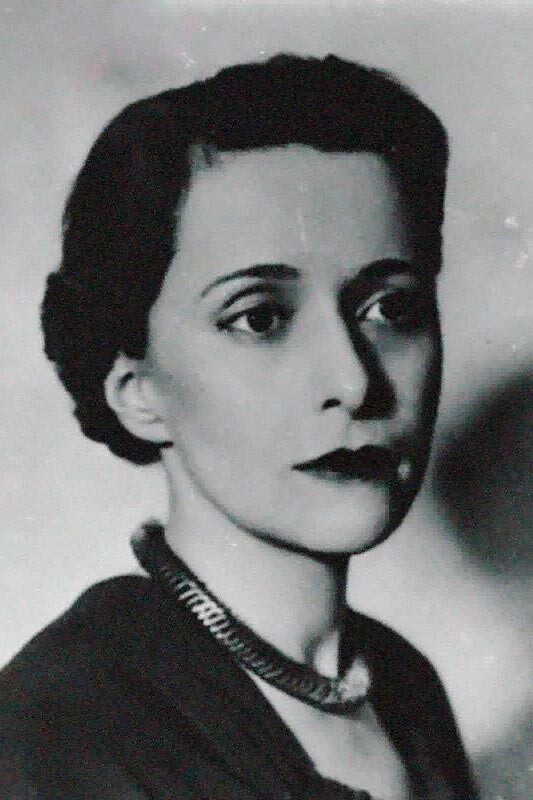

Yevgenia Ginzburg, 1967

Alexander Less/TASSGinzburg was born in Moscow into a Jewish family, studied at Kazan University and worked as a journalist. In 1937, she was arrested for alleged participation in a terrorist organization. As “father and mother of an enemy of the people” her parents were also detained.

After spending ten years in various prisons and camps, and almost the same many years without being able to return to her native Moscow, Ginzburg wrote one of the first accounts of the atrocities of the Soviet penal system and repressions. Her novel, Journey into the Whirlwind, is shocking with the descriptions of how women were treated in prison, and the real stories of why women were jailed during Stalin's time (for example, for simply “not denouncing” a neighbor).

The book was first published in Milan in 1967, and it only appeared in Soviet publications after the author's death, in the late 1980s. As Ginzburg had hoped, her son, the famous writer Vasily Aksenov, saw the book printed in their homeland.

Nina Berberova

Armenian Museum of Moscow and Culture of NationsHer almost century-long life included many incredible twists and turns. Berberova was born and raised in St. Petersburg. One of her husbands was the prominent Silver Age poet Vladislav Khodasevich. After the 1917 Revolution, the couple left Russia and lived for a long time in Paris, where they were at the center of Russian emigre cultural life. During the Nazi occupation Nina lived in a village near the French capital.

In 1950, Nina left for the U.S. without knowing any English. However, she quickly learned the language, began publishing an almanac about the Russian intelligentsia and taught Russian language and literature at several American universities.

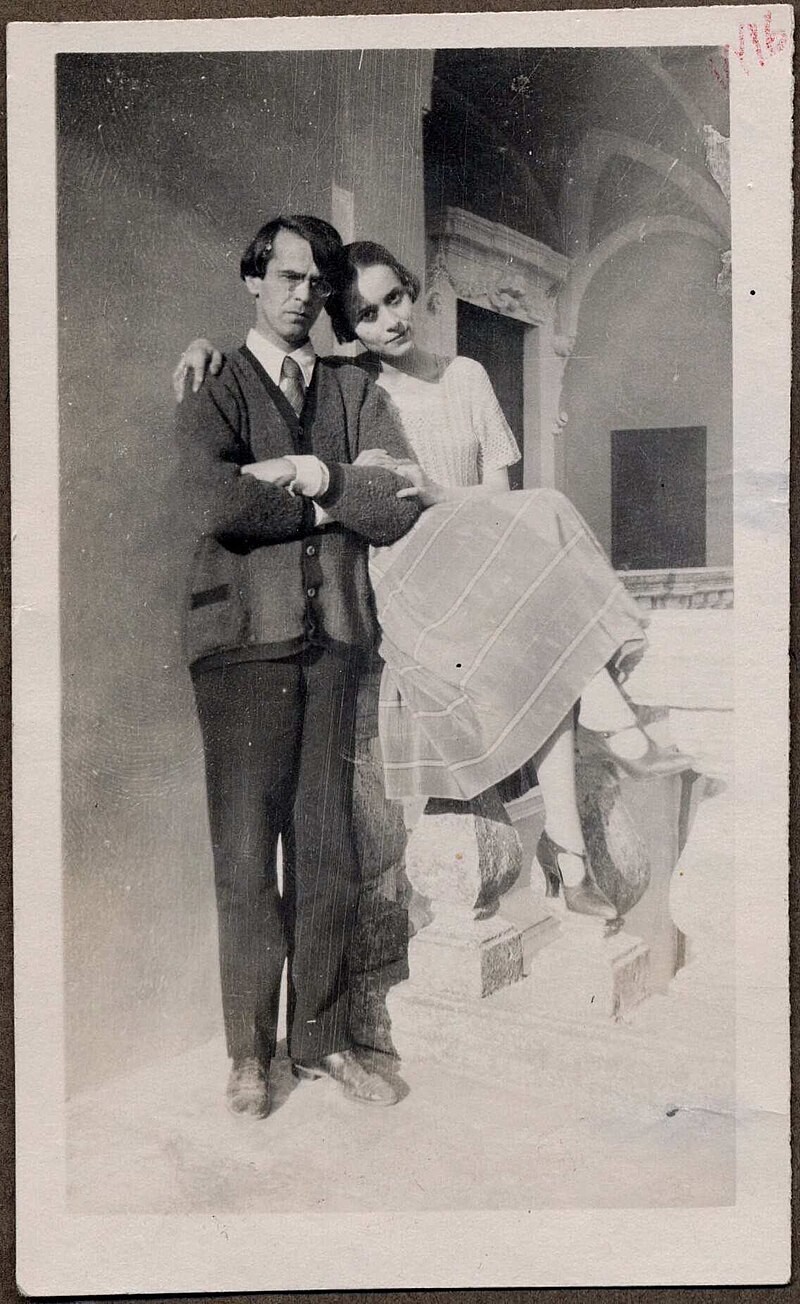

Nina Berberova and Vladislav Khodasevich in Sorrento, 1924

Public domainBerberova's main literary legacy is her autobiography, The Italics Are Mine, a treasure box of documentary evidence of the era and contemporaries. In addition, Berberova wrote several novels and one of the first biographies about the life of Tchaikovsky, where she spoke openly for the first time about his homosexuality.

Iron Woman is Berberova's book about Baroness Moore Budberg, the triple agent of the intelligence services of the USSR, Germany and England, who was the mistress of Maxim Gorky and then Herbert Wells.

Read more about Berberova here.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox