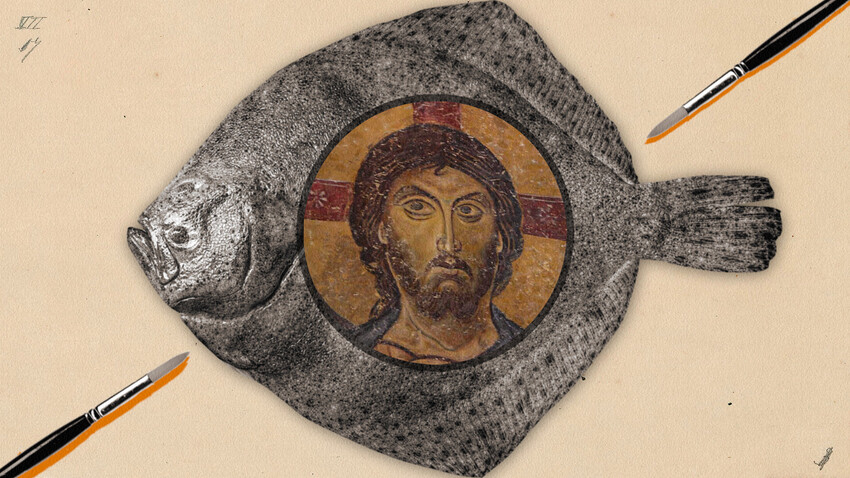

An icon painted on dried flounder is considered one of the rarest in existence - there aren’t that many left around. Two ended up in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg in 1906. They were made in the 19th century, using oil paint on either side of the fish. Both icons feature Jesus Christ and the Holy Mother of God.

Committing the images of saints to dried fish was an old Chumak tradition. But why the choice of material? And who were the Chumaks?

Fish is one of the most ancient Christian symbols. The Greek word for — ΙΧΘΥΣ (“ikhtis”) — is an acronym of the Greek phrase “Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ” - “Jesus Christ, son of God, savior”. It’s no accident that fish occupies such an important role in Biblical symbolism. Jesus, after all, managed to feed 5,000 people with just two fishes and five pieces of bread, while his apostles, Peter, Andrew and John were fishermen. Jesus himself referred to them as “fishers of men”.

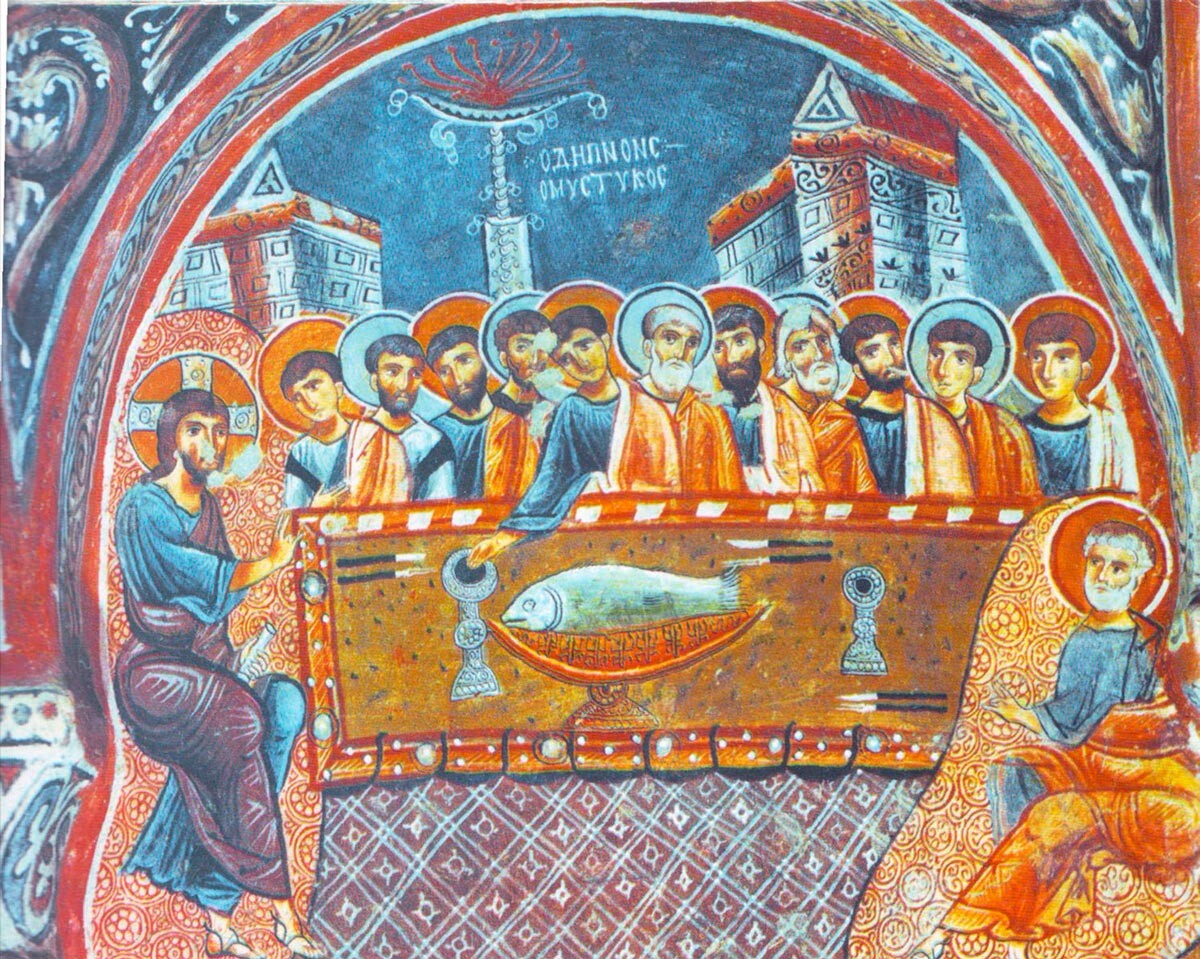

The Last Supper, a fresco in the Dark Church (Cappadocia, Goreme National Park), XIII century

Public DomainThe image of a fish with or without the ΙΧΘΥΣ monogram became the visual code for identifying one’s own in the age of Christian persecution at the hands of the Romans in the 2nd-3rd centuries AD. The decree on religious tolerance was signed in the year 313 - all imagery containing Jesus Christ had been strictly banned before then. Nobody had any problem with images of fish, however. And so, if two people met in the street and one drew a curve and another completed it by drawing another underneath - the two recognized each other as adherents of the same faith. The same symbol was used for Christian community meetings and burials.

The Chumaks in Little Russia, 1850-1860, Ivan Aivazovsky / State Russian Museum

Public DomainFinally, in order to make their icons, the Chumaks used not only symbolic material, but also one of the most accessible “canvases” in the 19th century - dried fish.

They were a class of people prominent in the 16-19th centuries living in Ukraine and the Russian South, who were in the business of shipping goods. Their prime commodities were fish and salt, although not exclusively. The Chumaks transported their merchandise from the sea to across the country and beyond, using established shipping routes spanning hundreds of kilometers.

Chumaks on vacation, 1885, Ivan Aivazovsky / National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus

Public DomainA typical chumak had several dozen carts and oxen at his disposal. Some entered into cooperation with others, with the subsequent caravan could have numbered up to 100-500 such carts. In the 1840s, there were on average 130,000 tons of merchandise transported from Crimea annually, with about 30,000 Chumaks involved. This also meant that losing an entire shipment would have been a huge risk; and the possibility of that happening did indeed exist: the caravans came under frequent attack from various bandits, seeking to get their hands on some valuable booty. This meant that the Chumak caravans would often hire muscle in the form of convoys to act as an escort and security. And, for the journey to be less risky, they’d bring amulets for protection - icons made with dry fish. They were hung inside the carriages (a bit like religious symbols hanging from the rear view mirror in cars today) and the Chumaks would also give charity to monasteries in the form of salt - a valuable commodity in those days.

Chumatsky Trakt in Mariupol, 1875, Arkhip Kuindzhi / State Tretyakov Gallery

Public DomainFish icons began to be phased out together with the Chumak trading guild, when the age of the railroad came knocking, making that type of business obsolete. Chumaks, for their part, remained only on the canvases of famous Russian artists, such as Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ivan Ayvazovsky, Aleksey Savrasov and so on.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox