By the arrival of the 1960s, Tolkien’s fame already reached the USSR. Books were brought back from rare trips abroad and distributed among those who could read English. Allegedly, among the first readers was Boris Grebenschikov, leader of Russia’s cult band ‘Akvarium’. In fact, he credits Tolkien’s novels for his love affair with fantasy (the famous album cover for ‘Treugolnik’ depicts two Elven writing styles - ‘Tengwar’ and ‘Cirth’).

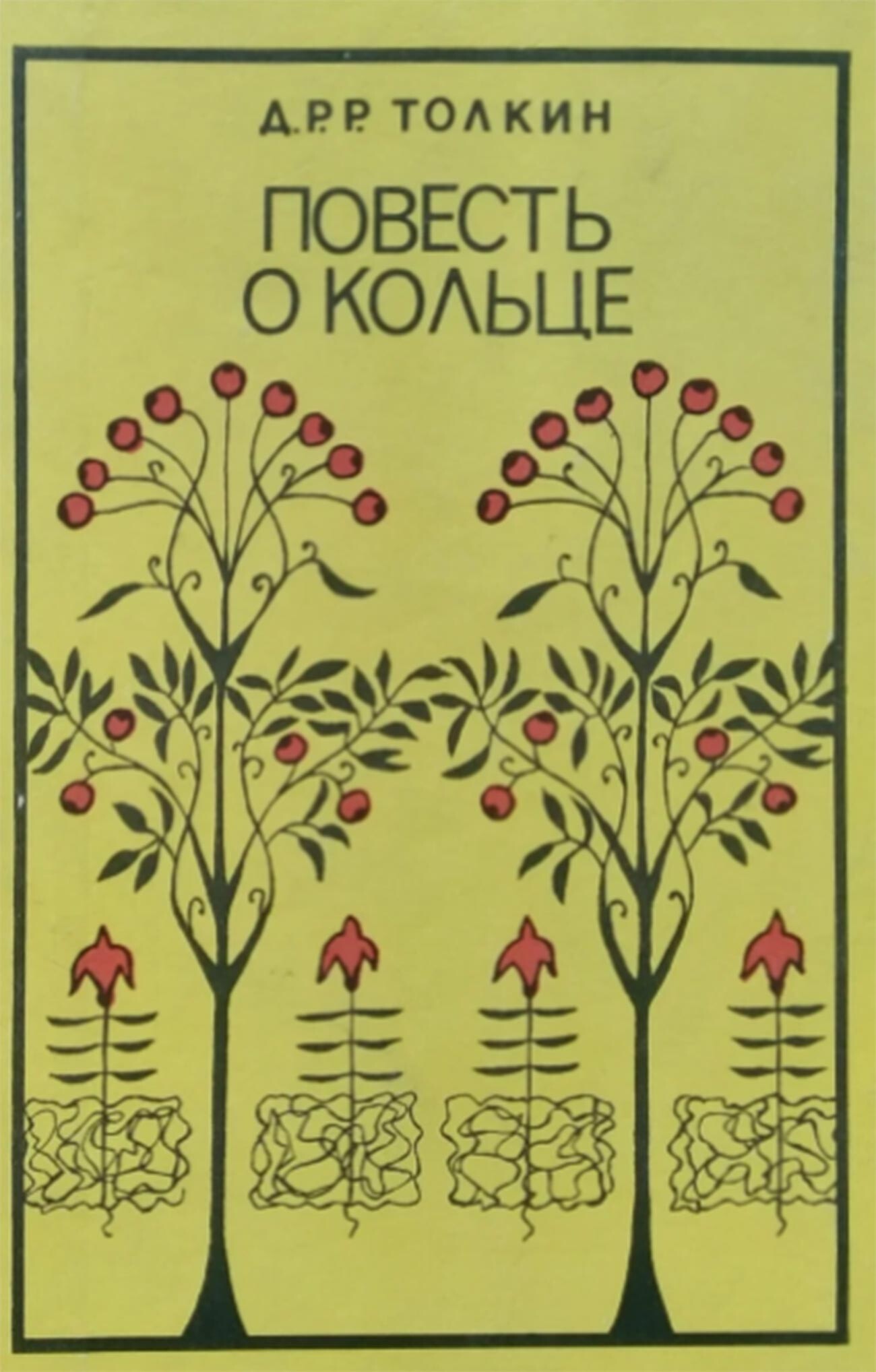

Russian translations of the ‘Lord of the Rings’ series used to be done by amateurs. The texts would be typed up by hand, then manually bound at home. There are no less than eight Soviet complete and incomplete translations, the most widespread of which was done by a Perm-based philologist named Aleksandr Gruzberg in 1976.

It was only in 1982 when a Moscow publishing house would publish an abridged children’s version of the first novel in the series, which the translators attempted to turn into more of a fairy tale. Young readers would storm bookstores and libraries for years in search of a sequel that didn’t exist. The full version would only arrive at the start of the next decade.

One of the first ‘The Lord of the Rings’ translations from 1966 is also a work of fan fiction. Zinaida Bobyr did more than just shorten the text - she introduced new story arches and even a new artifact - the Silver Crown. One of the books even contains sci-fi elements: it contains Rings-related tales told by characters from Polish author Stanislav Lem’s novel ‘Eden’.

The story is set in the future and sees archeologists discover the Ring. Using technology, they figure out its story and attempt to apply scientific reasoning to what’s happened. Bobyr knew what she was doing when committing the egregious crime of slamming the two worlds together into one narrative. It was simply done to expedite publishing, as sci-fi was already big in the USSR, but fantasy was still in its infancy.

As a result, the first version by Bobyr (the one without the sci-fi) was released only in the 1990s, riding the wave of Tolkienism, among others. Others followed suit, including ‘The Ring of Darkness’ by Nik Perumov - the unofficial sequel to ‘The Lord of the Rings’. Perumov started by imitating Tolkien, but found his own creative voice, becoming one of Russia’s most popular fantasy writers in the process.

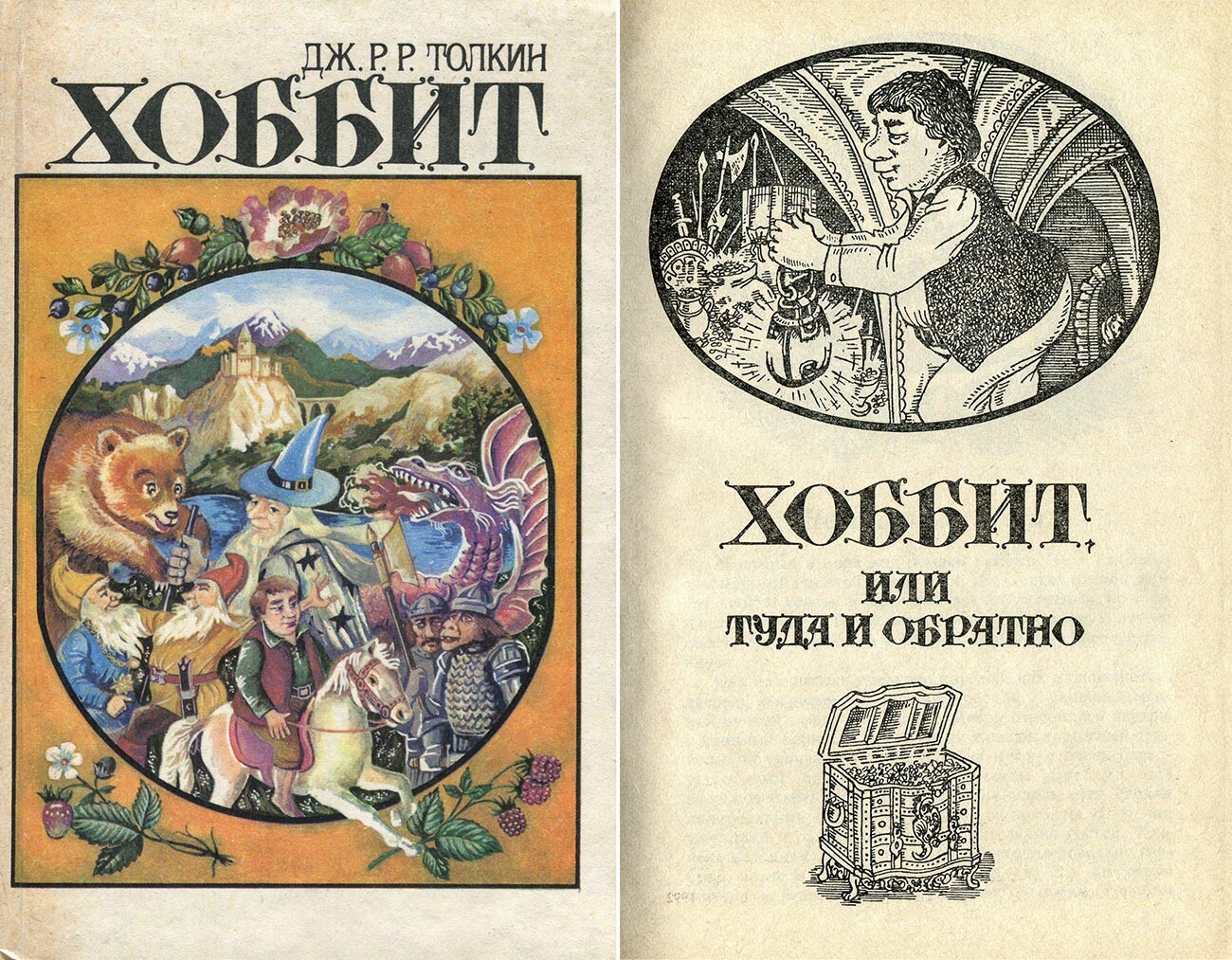

The novel ‘The Hobbit’ had more luck in the USSR, owing to the increased fantasy component. The first translation was issued in 1976, followed three years later by a children’s stage production in St. Petersburg, titled ‘The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins’, which ran for almost 10 years and was even adapted for TV (Western copyright laws were often ignored in the USSR).

In 1985, a Leningrad-based TV channel ran a series of televised stage productions dealing with ‘The Hobbit’ titled: ‘The Fantastic Travels of Mr. Bilbo Baggins’ - basically, another attempt at adapting the novel for theater, but with cameras. The story was shortened and the costumes and overall production looked cheap, but the budget surprisingly allowed for some visual effects.

In 1991, ‘Khraniteli’ (‘Guardians [of the Ring]’), a Soviet television play miniseries, had a similar feel. One of the aforementioned ‘Akvarium’s co-creators, Andrey Romanov, was tasked with providing the music. The recording was considered to have been lost for a long time, until someone uploaded it to YouTube in 2021. The online premiere caught the attention of Western media, including ‘Variety’ magazine, which published an entire story on the filming.

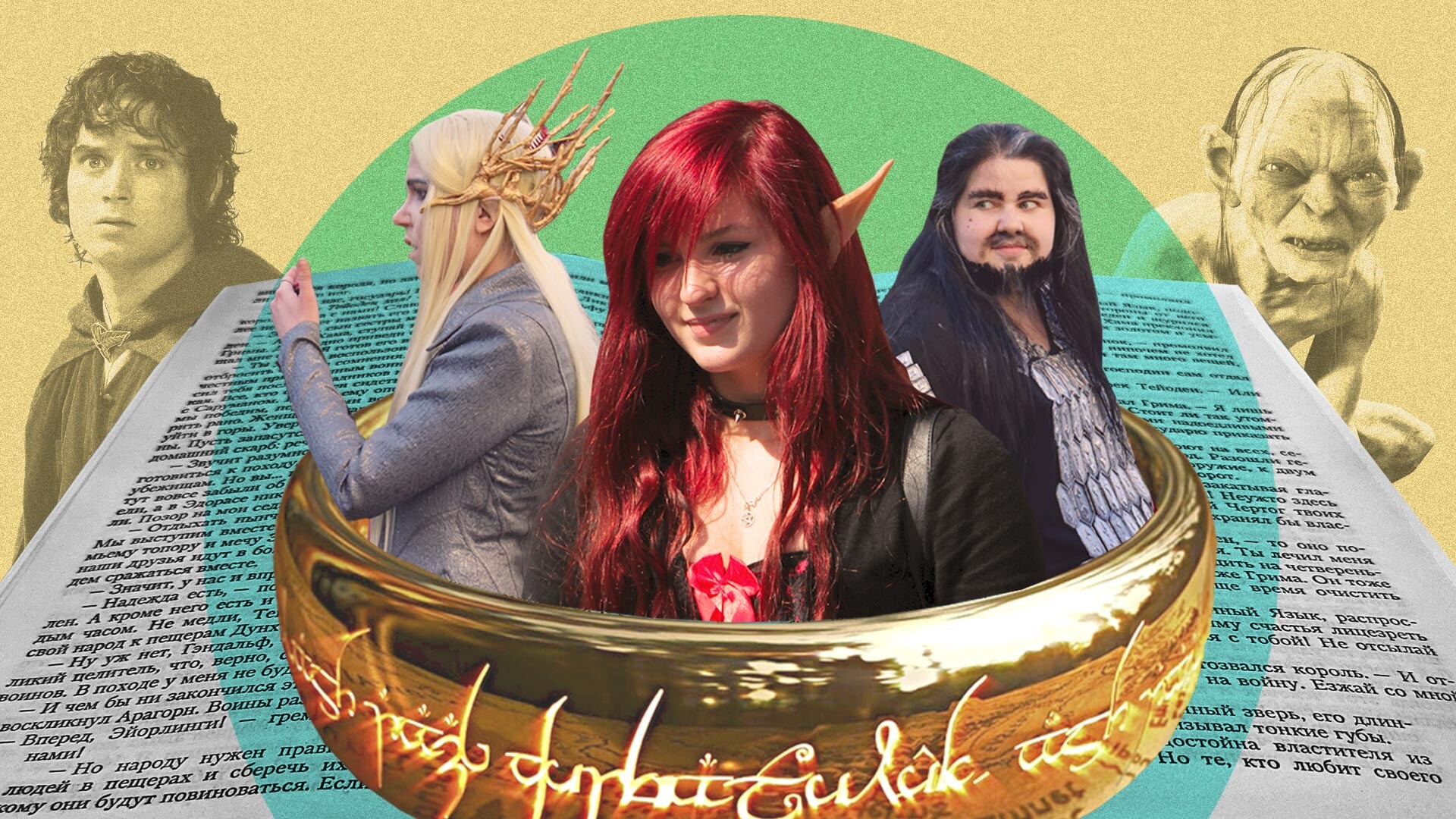

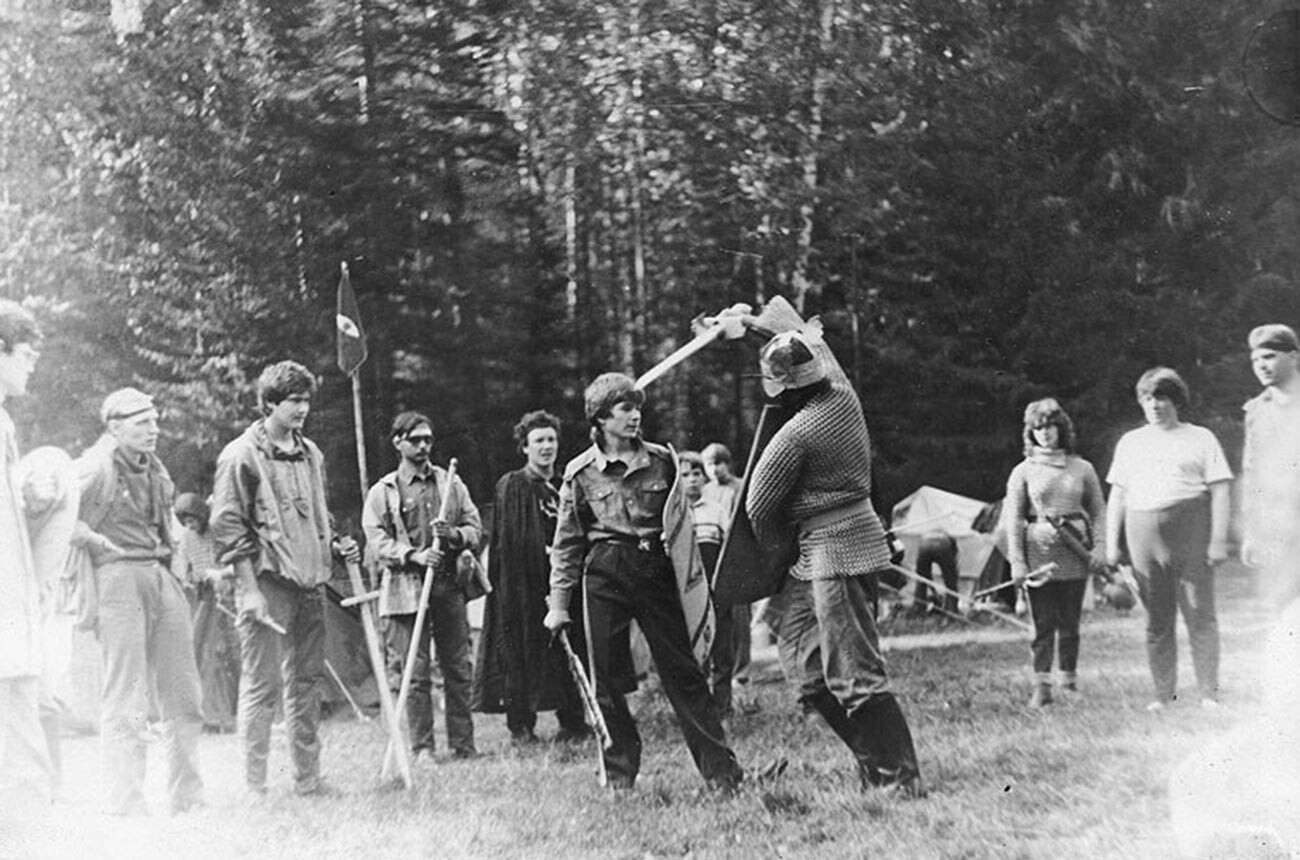

By the end of the 1980s, an entire subculture had sprung up. Its core was made up of members from numerous fantasy-related youth clubs, including so-called ‘communars’ - the first role-playing enthusiasts in the USSR and even hippies.

In 1990, just outside Krasnoyarsk in Siberia, the first Hobbit role-playing games were held, later becoming an annual affair.

In 1990s Moscow, the traditional meeting spot for Tolkienists was in Neskuchny Sad, which is practically Gorky Park. Members referred to it as ‘Eglador’, in honor of the first Elven kingdom in Middle Earth. Every Thursday, teens and young adults would gather with their capes made from drapes and shields made from road signs. The utopia didn’t last long, however, as, soon, more people of all walks of life joined and there were many unsavory characters there that sullied the entire movement’s reputation.

The club received a new lease on life when Peter Jackson’s famous trilogy hit theaters 20 years ago. According to the 2002 census, some 600,000 Russians identified as Elves, Hobbits or other fictional races. And many didn’t just wear elven capes and grow their hair out - there was even talk of people getting plastic surgery to lengthen their ears!

Not all Tolkienists are role-playing fanatics, however. There are those who write books, poetry and songs (appropriately themed, of course). In 2017, for instance, an opera based on ‘The Silmarillion’ premiered in Elvish, scored by the Russian Presidential Orchestra, no less. Folk band ‘Melnitsa’ and metal band ‘Epidemia’ are, likewise, examples of artists adopting Tolkienist themes in their music and lyrics.

There are even Middle Earth historians, who study the author’s biography, translate unpublished works and hold conferences, seminars, exams and write monographs.

Opera "Silmarillion. In Memory of Tolkien" at Delovoy Tsentr metro station in Moscow.

Alexander Avilov/Moskva agencyDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox