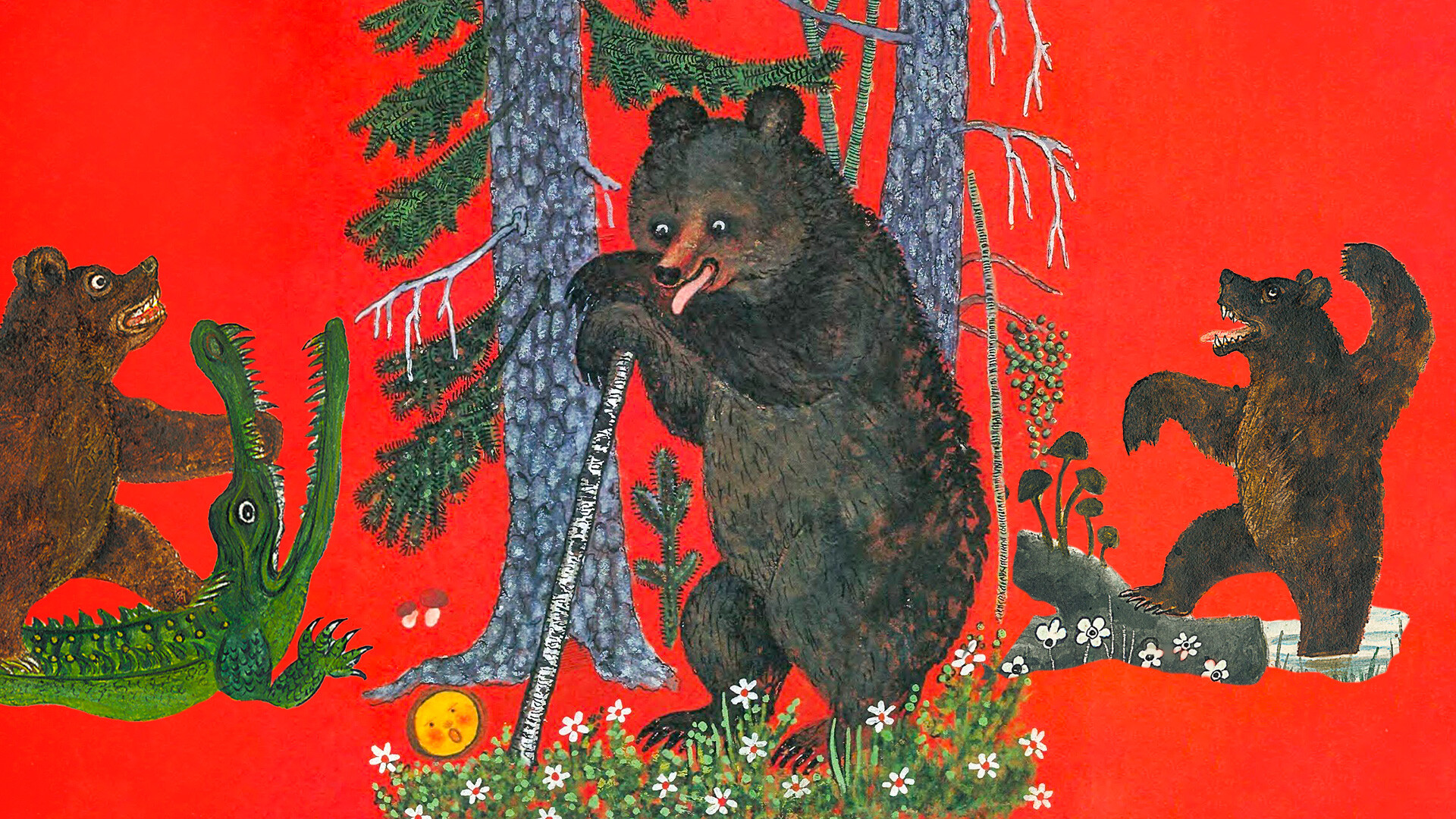

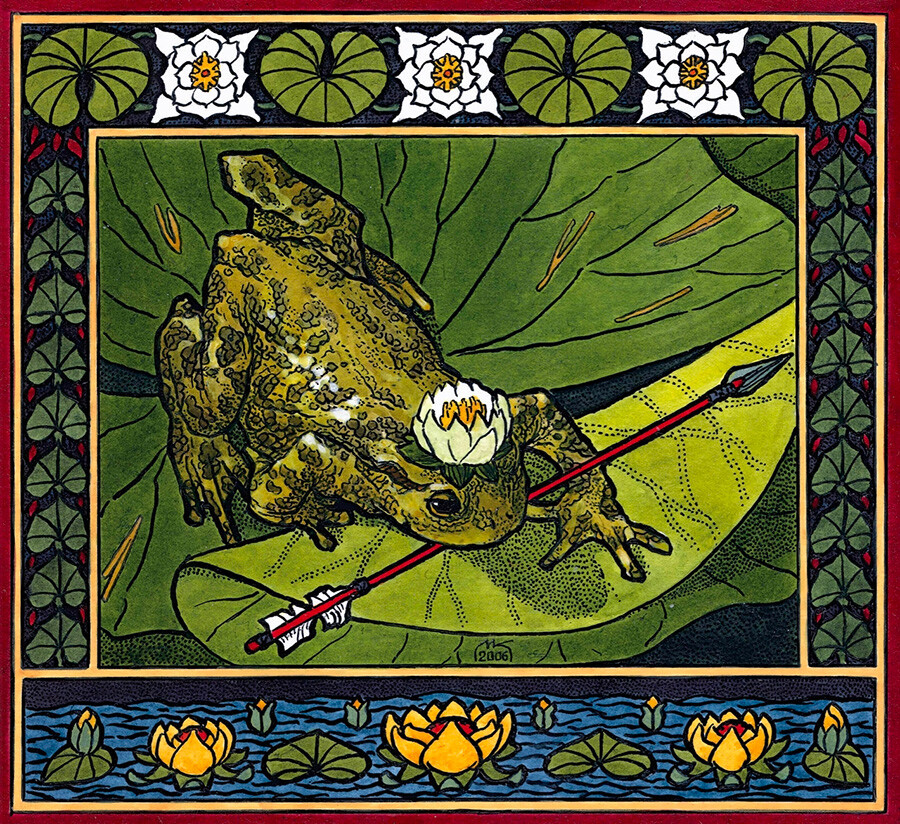

Ivan Bilibin’s illustration to the “Frog Princess”

Public domainFrogs, much like snakes, are representatives of the magical world, and are closely associated with wizards and dark forces. In Old Russia, the weather was sometimes forecasted based on a frog’s croak. In addition, certain crafty love-binding rituals were performed using these amphibians. In Russian folklore, the iconic witch Baba Yaga would typically prepare sinister magic potions made with frogs and toads in her pot.

Ivan Bilibin’s illustration to the “Frog Princess”

Public domainThe “Frog Princess” is one of the most popular Russian folk tales. An evil spell was cast that turned Vasilisa The Beautiful into a frog. Ivan Tsarevich had to marry the frog, after inadvertently shooting his arrow into the swamp where the frog lived - such was his father’s will. At certain times, however, Vasilisa was able to escape her frog skin and return to her true self – the beautiful, young woman, Vasilisa the Wise.

Vladimir Deulin “Frog Princess” (Jewelry box painted with a Palekh miniature, 1975)

Litfond auction houseHowever, later on Vasilisa would again turn into a frog. To help his wife, Ivan burnt the frog skin, but it turned out that he had violated the magical agreement. To get Vasilisa back, Ivan had to set out on a long journey and experience many trials.

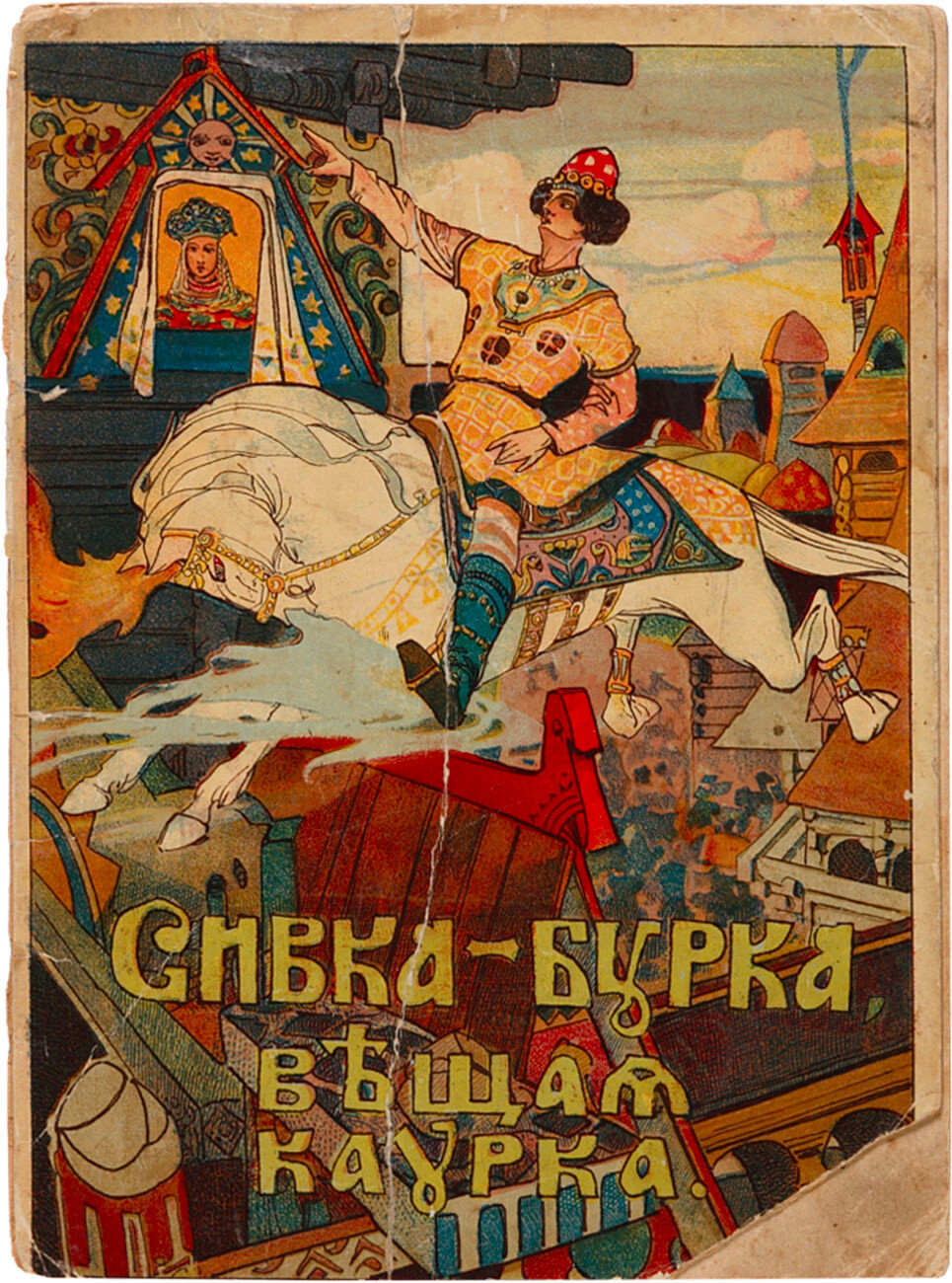

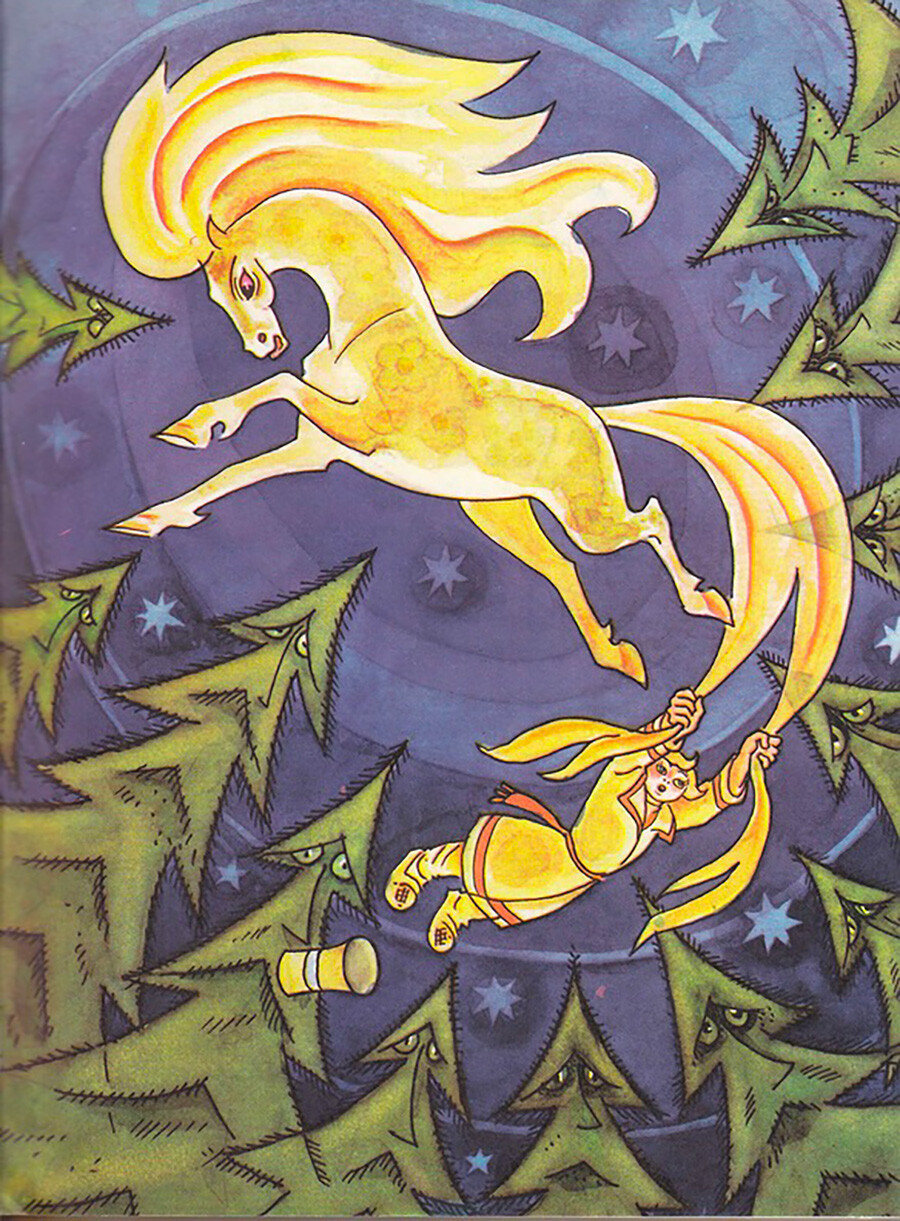

Illustration for “Sivka-Burka”. I.D. Satin Publishing House, 1906.

Public domainA horse was one of the most revered animals among the ancient pagan Slavs, and this is why the magnificent creature was often a central figure in quite a few folk tales. A horse was both a faithful friend and a freedom-loving animal. A wild horse was a symbol of Nature itself: when the horse galloped, the earth shattered, with steam coming out of its nostrils. The horseman who harnessed it became something almighty. On horseback, and exhibiting unbelievable strength and speed, is how Russian bogatyrs (warriors) were depicted in medieval epic songs (bylinas).

Viktor Vasnetsov. “The Bogatyrs”, 1898

Tretyakov GalleryThe tale about the magic horse Sivka-Burka is one of the most popular. This horse only appears to those who believe in it and who call out for it in an open field. Next, to earn its friendship and help one must complete a bizarre task - enter the animal’s right ear and exit through the left one. Sivka-Burka helps the tale’s hero to complete a nearly impossible task for the Tsar - ascend to the top a tall tower that no one has ever reached before, and then kiss the Princess.

Illustration to the folktale “The Humpty-Back Little Horse”

Dmitry BryukhanovQuite often, a horse in Russian folk tales boasts certain superpowers and magical abilities: it has wings and even takes the hero from one world to another. It can take him as far as the end of the Earth, where an ordinary human being would never be able to go on his own. A horse also helps Ivan Tsarevich rescue his bride, who is held captive by the evil Koschei the Immortal.

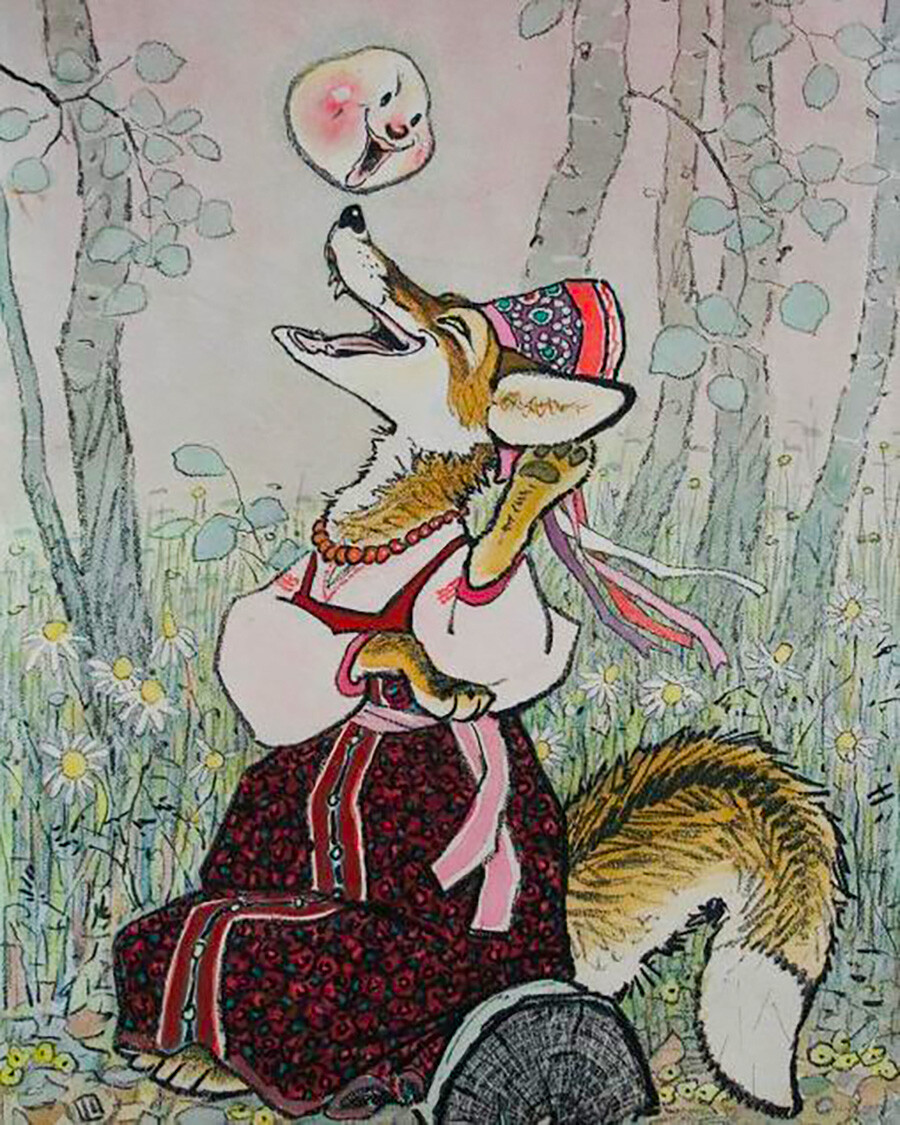

From an early age, Russian children know that the fox is the most cunning animal. Why? Because it was the only forest creature able to outwit the Kolobok! In the tale about Kolobok, the main hero is a spherical pastry made of dough who has run away from its grandma and grandpa and is rolling down a forest trail. Along the way, he came across a hare, a wolf and a bear, but managed to escape all of them by singing a cheerful song. Only the cunning fox said that it could hardly hear, and that way lured Kolobok into sitting closer, and eventually devoured him.

Evgeny Rachev. Illustration for the Russian tale “Kolobok”. 1964

Ulyanovsk Region art museumWhatever the case, it’s not only the weak and silly Kolobok who is deceived by a fox. In many Russian folk tales the fox personifies an evil force and is likely to leave a hapless victim high and dry. The story about a fox turning out to be more cunning than a strong and evil wolf is particularly popular. There’s even a well-known Russian saying: “A fox will fool as many as seven wolves.”

Well-known to Russian readers are the fables by Ivan Krylov, who often borrowed his plots from Aesop. One story tells about a crow and a fox. The latter gets its hands on the crow’s cheese through flattery.

A fox has at least two nicknames: “lisichka-sestrichka” (sister fox) and the more respectful one, as if to address an aged woman - “Lisa Patrikeevna” (in honor of the Novgorod Prince Patrikey, who manipulated people for his own profit). In the vernacular, there’s a highly popular comparison - “as cunning as a fox”, which is mostly used to describe women. This is the reason why a fox is usually a “she” in Russian folk tales.

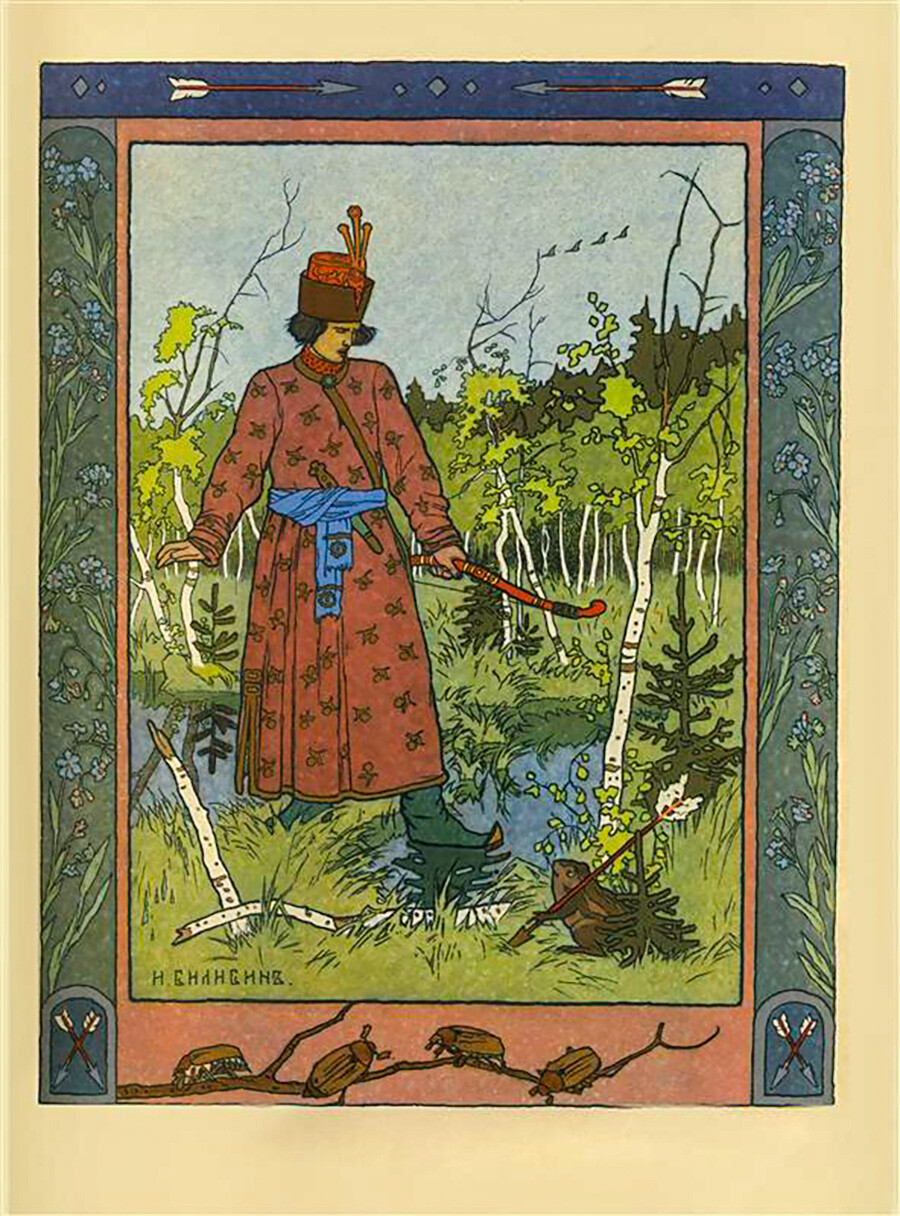

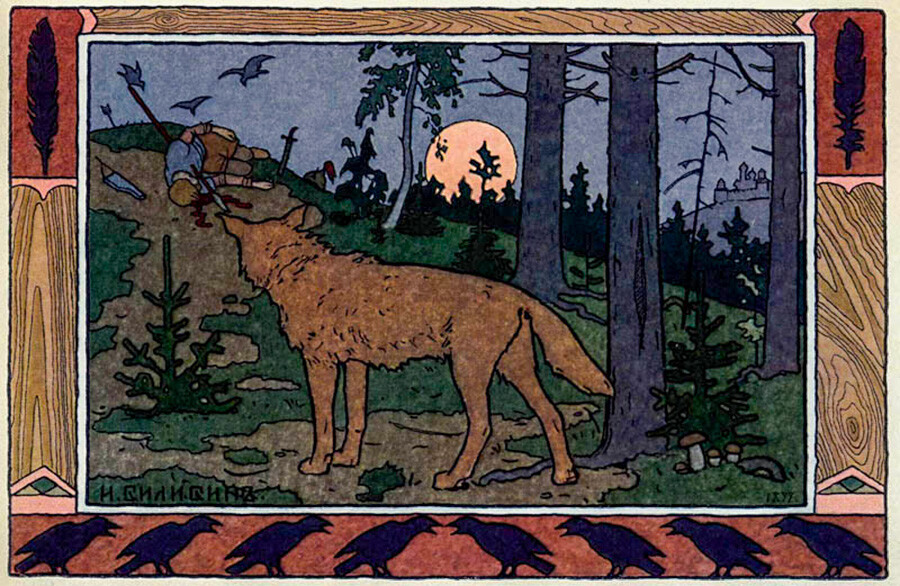

Ivan Bilibin’s illustration to the tale about Ivan Tsarevich, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf.

Public domainRussian forests abound in wolves, which live in packs and are naturally considered very dangerous animals. Moreover, they can appear in villages, steal a hen or eat sheep. In Russian folk tales, a wolf is often presented as a nefarious character that poses danger. At the same time, in order to avoid scaring the audience with such a powerful evil, the wolf is endowed with ridiculous traits, such as silliness and naïvety. Quite often in fairytales, a wolf is deceived by a cunning fox, which is to show that intelligence and wit can triumph over brute force.

Vasnetsov. “Ivan Tsarevich on the Gray Wolf”, 1889.

Tretyakov GalleryIncidentally, the gray wolf is also portrayed in a rather surprising way. For instance, in the famed tale about Ivan Tsarevich, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf, the wolf is depicted as a faithful and noble animal that carries the Tsarevich on its back. The wolf travels faster than a horse, and also helps the young man no matter what, even correcting his missteps.

Ivan Shishkin. “Morning in a Pine Forest”, 1889.

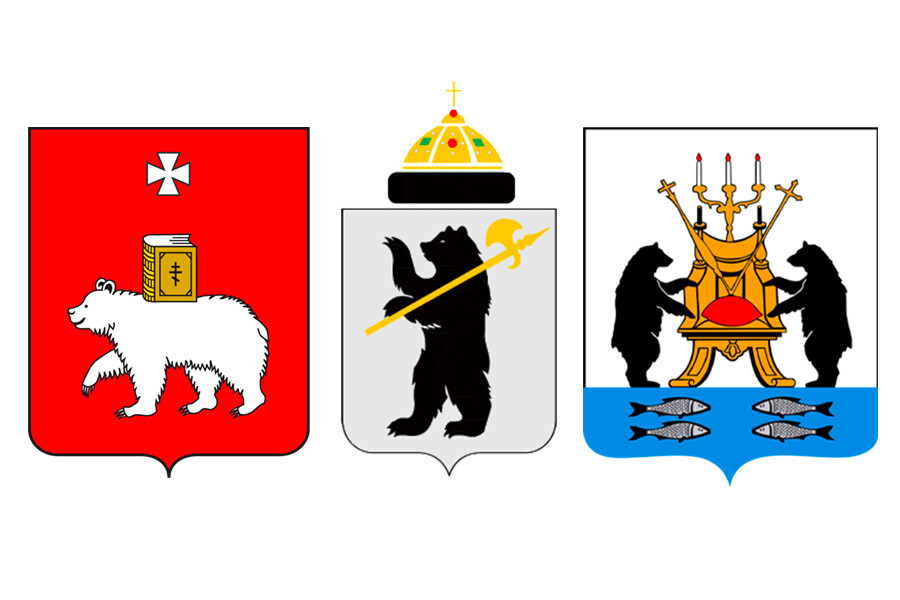

Tretyakov GalleryA brown bear is one of the most popular animals in Russian culture, and so it’s not surprising that the “Russian bear” is basically the country’s de facto symbol for people all around the world. The bear is also a popular character in caricatures of Russia. But it’s also frequently utilized in Russian heraldry, in the coats-of-arms of noble families, as well as numerous cities.

Left to right: the coats of arms of Perm, Yaroslavl, Veliky Novgorod.

Public domainWhile a lion is typically referred to as the “king of animals”, a bear was called “ruler of the forest” in Old Russia. This dangerous carnivore was certainly feared by everyone. Hunters lucky enough to survive an encounter with a bear would relish telling their story, embellishing the encounter with more and more wild details as time passed. Whatever the case, the fearsome animal was deeply revered and deemed to be sacred, and was a matter of awe and dismay among old Russians. It wasn’t even customary to call the bear by its proper name. Typically, one would use epithets like “kosolapy” (bruin), or the more affectionate “mishka” (little bear). There was a popular belief that such a respectful attitude would help avert danger. Also, bear claws and skin were kept as amulets to ward off evil.

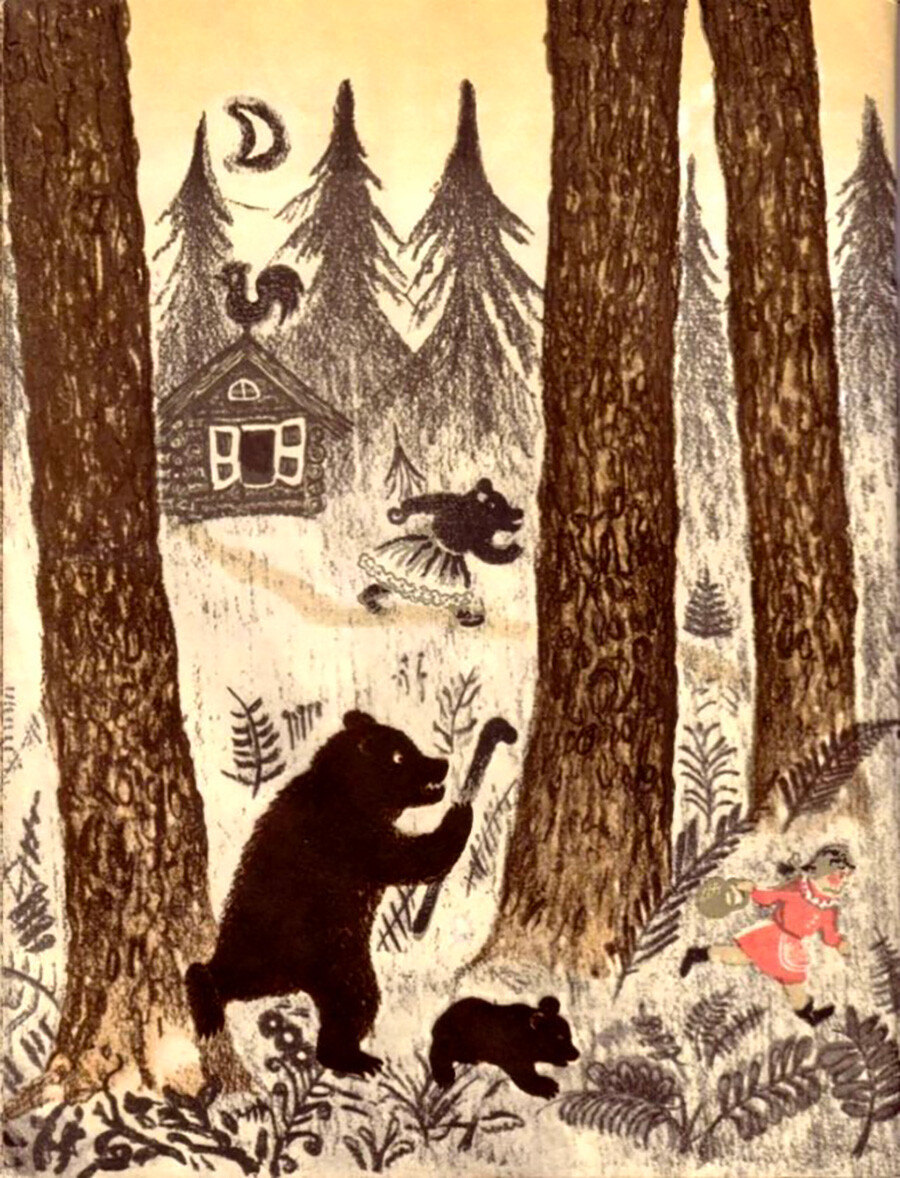

A 1935 illustration to the tale “Masha and Three Bears”, as retold by Leo Tolstoy.

Public domainMany of the nations that inhabited the territory of modern-day Russia created a cult of the bear. This was particularly common among the pagans, who had a great many rituals connected with bears. These included various hunting rituals, as well as special chants that would calm the soul of a slain animal. Also, some pagan tribes in Siberia would swear on the soul of a dead bear.

Yet, in Russian folk tales, the image of a bear is quite controversial. On the one hand, it is a defender of the weak and a ruler of the forest that justly settles conflicts among other animals. On the other hand, a bear is often portrayed as a kind and even naive and narrow-minded giant, a slouch in other words. The famous fairytale,“Teremok”, depicts how different animals came one by one to live in an empty house (terem). The huge bear, however, couldn’t fit inside and destroyed the house by sitting down on the roof. Eventually they built a new one, though, and lived all together in peace.

Evgeny Charushin. Color print “Teremok”

Russian North culture museumBears are also widely featured in stories about Russian saints, since they help to convey the idea of genuine love. For instance, St. Sergius Radonezhsky (of Moscow) fed a starving bear and thus tamed it. St. Seraphim Sarovsky was also capable of hand-feeding a bear.

Mikhail Nesterov. “Venerable Sergius’ youth”, 1892—1897

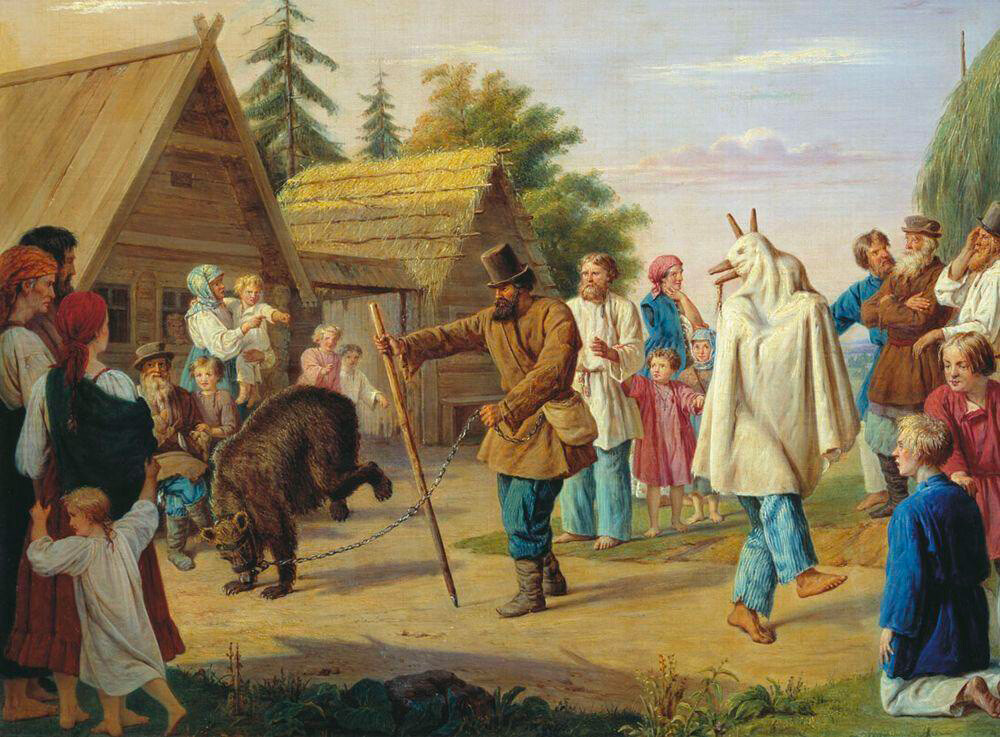

Tretyakov GalleryContemporary animal rights activists would certainly be very angry with this type of entertainment. Up until the late 19th century, a chained and trained bear was a common spectacle at folk festivals and various holidays. Also, ryazhenye - people dressed up as a bear - were traditionally invited to peasant weddings. This taming of the “taiga’s ruler” was seen as the symbol of Christianity triumphing over pagan beliefs.

François Riss. “Skomorokhi (wandering minstrels) in a village”, 1857.

Public domainDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox